Chapter 23 Approach to the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Infection

Chapters 24 through 27 describe in detail aspects of pneumonia caused by specific pathogens. This chapter provides a framework from which to approach the individual patient in whom a pulmonary infection is likely. Assessment may begin by gathering specific information consisting of answers to the set of questions presented in Box 23-1. In this chapter, each of these questions is addressed in turn, although in clinical practice, the steps in this approach to the patient may be considered in parallel. Answers to the questions “Is it infection?” and “How severe is the illness?” are perhaps the most important.

The Approach

Is It Infection?

A careful history and physical examination are essential. No universally effective approach is recognized, however, and good clinical judgment often will be needed (Table 23-1). Typically, the patient with pulmonary infection will be pyretic and will have a cough characterized by purulent sputum. Rigors are even more specific to this disorder but occur only in more severe infections. An abrupt onset with pleuritic chest pain is a classical presentation in pneumonia but often is lacking. Wheeze may be present in airway infections, and focal chest signs are common in pneumonia. The more specific pneumonia signs of bronchial breathing, egophony, and whispering pectoriloquy are rare. Unfortunately, in real life, the presence of advancing age and immunosuppression can mean that infection is present despite the absence of any of these signs, and underlying lung disease may mean that some of them are present in the absence of infection.

Table 23-1 Features of Respiratory Infection and Alternative Causes

| Feature | Pointer to Infection | Other Common Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Cough | Purulent sputum | |

| Temperature | Pyrexia Rigor | |

| Sweats | “Drenching” and occurrence at night suggestive of tuberculosis | |

| Chest signs | Features of consolidation | |

| White cell count | Raised | |

| C-reactive protein | Raised | |

| Chest radiographic appearance | Focal shadowing |

What Type of Infection is It?

Classification of Pulmonary Infections

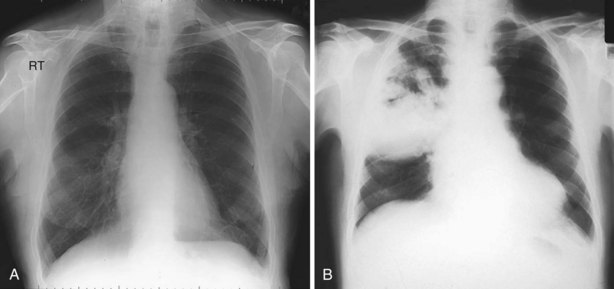

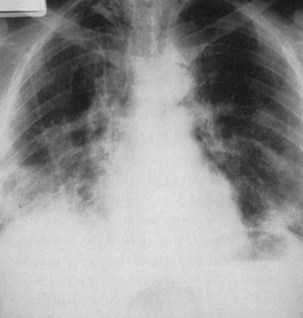

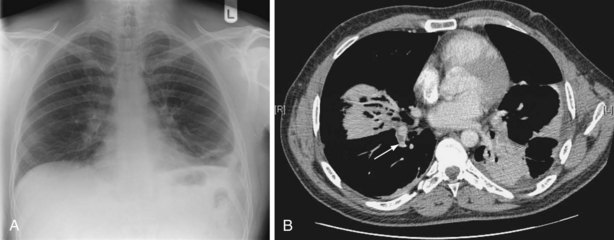

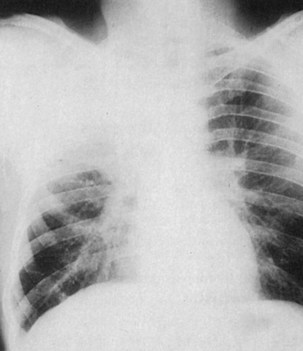

The two main groups of acute adult pulmonary infections encountered in hospital practice are acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (see Chapter 43) and pneumonia (Chapters 24 and 25). A chest radiograph is the key to separating these two, because it is the most sensitive screening method for detecting pulmonary consolidation (Figure 23-1, A and B). The presence of focal crackles is the most common feature of underlying consolidation. A pleural rub, or features of pleural effusion, may coexist. Other less common features include diarrhea, hypotension, and, in the elderly, mental confusion, hypothermia, and urinary incontinence. When pneumonia is suspected on clinical grounds and the chest radiograph is normal in appearance, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan may show changes in the lung parenchyma. However, other diseases may mimic pneumonia or be complicated by pneumonia (Figures 23-2 to 23-4).

Figure 23-2 Pulmonary eosinophilia. Right upper lobe consolidation may mimic pneumonia, as in this case.

It is important to identify the likely type of pneumonia according to the setting in which the infection was acquired (Table 23-2). The spectrum of pathogens differs for the five pneumonia types—community-acquired, early, and late nosocomial; immunosuppression-related; and aspiration.

Table 23-2 Classification of the Pneumonias According to Likely Origin and Immune Status

| Pneumonia Group | Likely Pathogens |

|---|---|

| Community-acquired | |

| Nosocomial, early | |

| Nosocomial, late | |

| Immunocompromised | |

| Aspiration |

How Severe is the Illness?

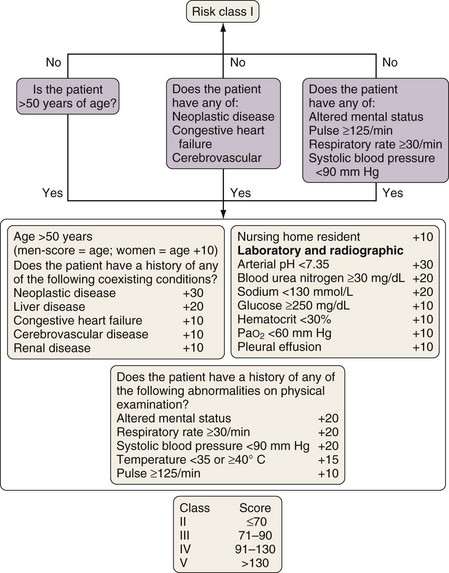

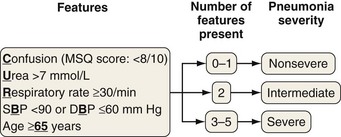

Among patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), those who die usually are severely ill at presentation, so the correct interpretation of presenting features is important. This information should be supplemented by the results of investigations as they emerge. Scoring systems have been developed as an aid to clinical judgment to assess CAP severity. The Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) is a two-step severity score built from 20 clinical and laboratory features (Figure 23-5). It has been validated in a number of studies mainly as a tool for keeping low-risk patients out of the hospital. The simpler CURB-65 index also is well validated and is based on just five clinical features (Figure 23-6), whereas CRB-65, which may be used outside the hospital setting, is based on four. Comparisons of the scores confirm the slightly greater accuracy of the PSI but simpler application of CURB-65 and CRB-65. Use of these scoring systems is recommended in the most recent CAP management guidelines.

In nosocomial pneumonia as well as pneumonia in the immunocompromised patient, the importance of presenting features as opposed to features that develop during the course of the illness is less clearly defined than for patients who have CAP. Previous or inappropriate antibiotic therapy, renal failure, prolonged mechanical ventilation, coma, shock, and infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp., and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are additional markers for severe nosocomial pneumonia (Box 23-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree