Approach to and Management of Mesenteric Vascular Disease

Leslie Cho

Jeffrey A. Skiles

INTRODUCTION

Acute mesenteric ischemia may be caused by embolic/thrombotic arterial occlusion, nonocclusive mesenteric arterial insufficiency, or mesenteric venous occlusion. Chronic mesenteric ischemia is usually related to progressive atherosclerotic narrowing of the mesenteric arteries. Because of the wide range of causes, mesenteric ischemia often goes undiagnosed and untreated, leading to high morbidity and mortality. This chapter reviews the clinical features, diagnosis, and management of patients with acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia. Acute mesenteric ischemia may be due to embolic mesenteric artery occlusion, thrombotic mesenteric artery occlusion, mesenteric venous occlusion, and nonocclusive mesenteric occlusion. A thorough understanding of mesenteric arterial anatomy is crucial to understanding and managing these patients.

Clinical Anatomy

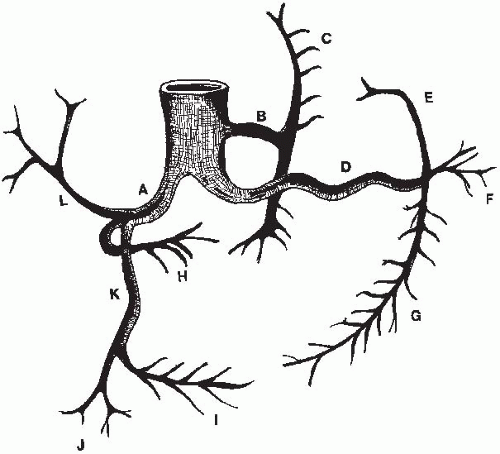

The gastrointestinal tract is supplied by the celiac trunk, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The celiac trunk originates from the anterior aorta just below the diaphragm at the level of the thoracic vertebrae 12 (T12) or the first lumbar vertebra (Fig. 15.1). It branches into the common hepatic, splenic, and the left gastric arteries. The left gastric artery supplies the lesser curvature of the stomach and collateralizes with the right gastric artery branch of the hepatic artery. The common hepatic artery gives off the hepatic and gastroduodenal artery, which supplies the distal stomach and duodenum. In a minority of patients (15%), the gastroduodenal artery branches off from the SMA. The gastroduodenal artery supplies the greater curvature of the stomach via the right gastroepiploic artery.

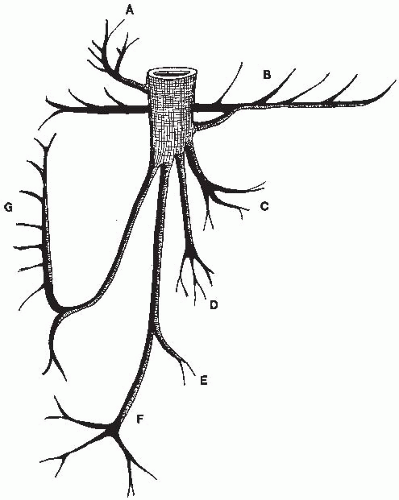

The SMA is located few centimeters below the celiac artery usually around the first lumbar vertebra at 20- to 30-degree caudal angulation and supplies the pancreas, duodenum, jejunum, and the right half of the colon. The branches of the SMA are the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, the jejunal and ileal branches, the ileocolic artery, the right colic artery, and the middle colic artery (Fig. 15.2).

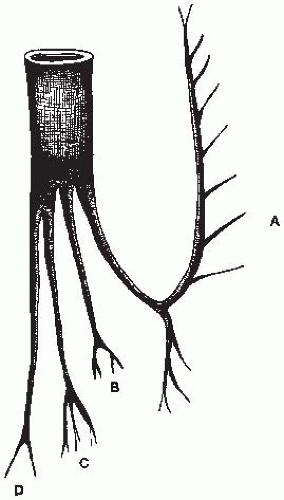

The IMA originates from the mid to distal infrarenal aorta around the third lumbar vertebra, which is usually 5 cm or more below the origin of the SMA. It supplies the distal transverse, left, and sigmoid portions of the colon and the rectum. Its branches are the left colic artery, the sigmoid (inferior left colic) arteries, and the superior rectal artery (Fig. 15.3). The SMA and IMA collateralize via the marginal artery of Drummond and the meandering mesenteric artery.

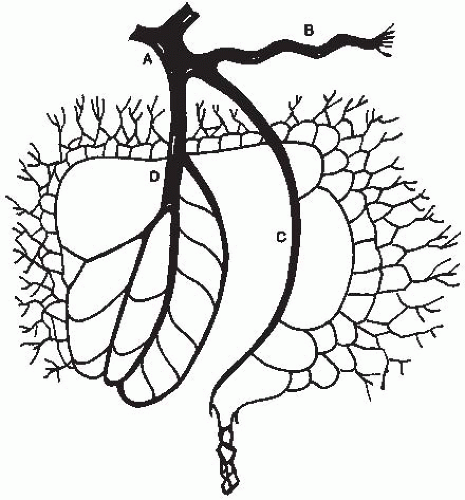

The venous drainage follows a similar pattern as the arterial circulation, with the vena recta forming a venous arcade that drains the small bowel and proximal colon through the ileocolic, middle colic, and right colic veins to form the superior mesenteric vein (Fig. 15.4). The superior mesenteric vein and the splenic vein join and continue to the liver as the portal vein. There are three areas especially vulnerable to ischemia during low-flow states because of their more remote position between the major arteries. These are the hepatic flexure of the colon between the ileocolic and the middle colic branches of the SMA, the splenic flexure between the middle colic and the left colic arteries, and the distal sigmoid and rectum.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

Acute mesenteric ischemia (Table 15.1) most commonly occurs as a result of embolism, acute thrombosis on preexisting atherosclerotic disease, or a low-flow state caused by systemic illness. Prompt diagnosis requires a

high index of suspicion since even with aggressive treatment, a patient with acute mesenteric ischemia has 40 to 50% mortality. Table 15.1 summarizes clinical features for acute mesenteric ischemia based on etiology.

high index of suspicion since even with aggressive treatment, a patient with acute mesenteric ischemia has 40 to 50% mortality. Table 15.1 summarizes clinical features for acute mesenteric ischemia based on etiology.

Acute Embolic Mesenteric Artery Occlusion

Acute ischemia may be caused by mesenteric arteries becoming occluded by emboli. The SMA receives 3 to 4% of all arterio-arterial emboli. Atrial fibrillation with left atrial thrombus, mitral stenosis with left atrial thrombus, and transmural myocardial infarction with mural thrombus are the most frequent sources of emboli. Other causes are proximal aortic atheroma, left atrial myxoma, and paradoxical emboli from venous circulation.

Clinical Features. Embolic mesenteric occlusion occurs in patients with one or more of the cardiac risk factors described above and usually without antecedent history of weight loss or intestinal angina. One third of patients may

have had a prior history of peripheral embolic episodes. Usually, patients describe sudden onset of severe abdominal pain. The nature of the pain has been described as initially crampy and then constant. Abdominal pain is the most common manifestation of ischemia and is often described as severe and “pain out of proportion to the exam.” Rapid evacuation of the bowel sometimes occurs. Leukocytosis, hemoconcentration, and systemic acidosis are often seen. Elevated serum amylase, alkaline phosphatase, and creatinine phosphokinase may indicate bowel infarction. There are few physical examination signs of early acute mesenteric ischemia. If the ischemia progresses without intervention, patients can have abdominal distention, signs of peritoneal irritation, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

have had a prior history of peripheral embolic episodes. Usually, patients describe sudden onset of severe abdominal pain. The nature of the pain has been described as initially crampy and then constant. Abdominal pain is the most common manifestation of ischemia and is often described as severe and “pain out of proportion to the exam.” Rapid evacuation of the bowel sometimes occurs. Leukocytosis, hemoconcentration, and systemic acidosis are often seen. Elevated serum amylase, alkaline phosphatase, and creatinine phosphokinase may indicate bowel infarction. There are few physical examination signs of early acute mesenteric ischemia. If the ischemia progresses without intervention, patients can have abdominal distention, signs of peritoneal irritation, and gastrointestinal bleeding.

FIGURE 15-3. Normal anatomy of the IMA and its major branches. (A, Left colic artery (superior and inferior branches); B, lower left colic artery; C, sigmoid artery; D, superior rectal artery.) |

FIGURE 15-4. Normal anatomy of the mesenteric venous system. (A, Portal vein; B, splenic vein; C, inferior mesenteric vein; D, superior mesenteric vein.) |

TABLE 15.1 ACUTE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIC CONDITIONS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diagnosis. There are no abdominal x-ray signs for the early diagnosis of mesenteric artery occlusion. Radiographs are helpful in discerning free air resulting from perforation. Plain x-ray may rule out other causes of an acute abdomen such as the presence of small bowel obstruction, renal or biliary stone, chronic calcific pancreatitis, or a perforated viscus. Late findings range from “thumbprinting,” which signifies intramural edema or hemorrhage, to pneumatosis or portal vein gas, which represents bowel infarction. Frequently, mesenteric artery occlusion from embolism occurs in patients in the intensive care setting who are intubated, and laboratory abnormalities such as significant uncorrected metabolic acidosis from increasing lactic acid or unexplained persistent leukocytosis may be the first sign. Unfortunately, these signs occur when ischemic bowel has progressed to infarction.

Duplex scanning has been advocated in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. However, the inability to obtain accurate B-mode images, difficulty in obtaining a good image in patients with truncal obesity,

visualization difficulties depending on bowel gas pattern, tortuosity of the vessel, and technician inexperience make duplex scanning still a questionable modality.

visualization difficulties depending on bowel gas pattern, tortuosity of the vessel, and technician inexperience make duplex scanning still a questionable modality.

Angiography with delayed filming to demonstrate the venous phase is the gold standard in the setting of suspected mesenteric ischemia when no signs of peritoneal irritation exist. Lateral aortography should be performed as the initial study to identify the origin of the mesenteric vessels. Selective cannulations of the celiac, SMA, and IMA can usually be performed using a JR4 catheter in the lateral projection. In some cases, catheters with longer tips, such as SOS or the Cobra catheter, may be needed for selective injections. For good quality mesenteric angiograms without streaming, the rate of injection should match the flow rate of the vessel being studied. The typical flow rates are 10 mL/s for the celiac trunk, 8 mL/s for the SMA, and 3 mL/s for the IMA. Digital subtraction angiography acquisition may be less helpful for mesenteric angiography because of the presence of bowel gas. In individuals who are being evaluated for GI bleeding, the clinically suspected vessel should be injected first. Arteriography may help in distinguishing the different causes of acute mesenteric ischemia. A “meniscus” sign located 4 to 6 cm from the origin of the SMA is the classic angiographic finding in mesenteric artery occlusion from an embolus. Emboli typically lodge distal to the origin of either the middle colic artery or the first jejunal branch of the SMA. Therefore, the proximal jejunal branches fill rapidly on the angiogram, while the distal jejunal and ileal branches fill slowly.

Acute Thrombotic Mesenteric Artery Occlusion

Clinical Features. Acute SMA thrombosis with the development of intestinal ischemia commonly afflicts women in their 60s and 70s. It often occurs in patients with preexisting chronic mesenteric ischemic symptoms such as weight loss, altered bowel habits, and chronic abdominal pain. Acute SMA thrombotic occlusion is typically associated with preexisting SMA atherosclerosis, although it has been associated with fibromuscular dysplasia, hypercoagulable states, inflammatory arteritis, and aortic dissection.

Diagnosis. As with acute mesenteric ischemia from embolism, radiographs are not helpful. Angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of acute mesenteric artery occlusion from thrombus. Atherosclerosis of the SMA most commonly affects the origin and proximal few centimeters of the artery. Unlike SMA embolus, there is a sharp cutoff in the proximal 3 cm of the SMA without jejunal branch sparing. Extensive collateral circulation from the celiac artery or IMA is often seen in patients with thrombotic mesenteric artery occlusion.

Acute Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis

Clinical Features. Mesenteric venous thrombosis encompasses a wide range of presentations from asymptomatic nonocclusive thrombus to portal venous occlusion with associated liver failure and extensive bowel necrosis. Mesenteric vein occlusion accounts for approximately 10% of

acute mesenteric ischemia. There are multiple causes of mesenteric vein occlusion, including hypercoagulable state, abdominal malignancies, prior abdominal operations, oral contraceptive use, and inflammatory abdominal disease (Table 15.2). When mesenteric vein occlusion occurs, fluid begins to accumulate in the wall and lumen of the affected intestine. If diagnosis is not made early, thrombosis may extend into the vasa recti and intramural venous collaterals. When this occurs, the arterial circulation is compromised from the decrease in effective perfusion pressure resulting from the increase in capillary pressure.

acute mesenteric ischemia. There are multiple causes of mesenteric vein occlusion, including hypercoagulable state, abdominal malignancies, prior abdominal operations, oral contraceptive use, and inflammatory abdominal disease (Table 15.2). When mesenteric vein occlusion occurs, fluid begins to accumulate in the wall and lumen of the affected intestine. If diagnosis is not made early, thrombosis may extend into the vasa recti and intramural venous collaterals. When this occurs, the arterial circulation is compromised from the decrease in effective perfusion pressure resulting from the increase in capillary pressure.

Acute mesenteric venous occlusion with sudden abdominal pain has been associated with bowel infarction and peritonitis. In patients with subacute mesenteric vein occlusion, abdominal pain may have been present for several days to weeks without bowel infarction or variceal hemorrhage. Chronic mesenteric venous occlusion usually presents with complications of portal or splanchnic vein thrombosis such as variceal bleeding. Patients with chronic occlusion do not complain of pain because of their extensive collateral formation.

Diagnosis. Physical exam and routine blood test are not helpful in the diagnosis of mesenteric vein occlusion. Abdominal radiographs may show “thumbprinting,” which is a blunt, semiopaque indentation of the bowel

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree