Takayasu’s Arteritis

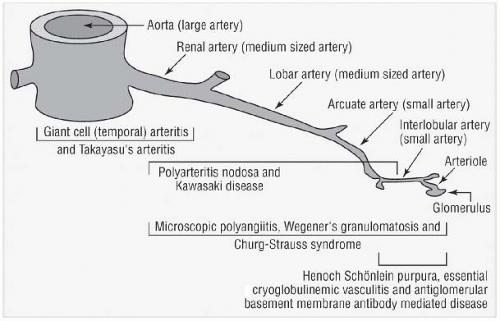

TA is a chronic granulomatous panarteritis affecting large elastic arteries such as the aorta and its main branches, the coronary arteries, and occasionally the pulmonary arteries. Inflammation results in stenosis, occlusion, or aneurysm formation and potentially secondary thrombosis. Early reports emphasized a “triphasic” disease process: a “prepulseless” phase characterized by nonspecific inflammatory symptoms, followed by painful arteries, and ending in “burned-out disease” with vessel occlusion and distal ischemia. Prospective evaluation of patients with TA, however, has revealed significant variability in disease course rather than these distinct stages of disease.

Epidemiology

The prevalence rates and distribution of involved vessels differ between ethnic groups. High prevalence rates are reported in Asian countries, such as Japan, Korea, China, and India. TA is less common among white populations. The estimated peak age of disease onset is in the third decade, and the disease is more common in women.

Clinical Features

Musculoskeletal and constitutional findings are present in 30 to 40% of patients. Since 20% of all TA patients are completely asymptomatic, the disease may be discovered with the finding of an asymptomatic bruit (widespread bruits are common in TA) or diminished pulses. Other patients may present with claudication of arms or legs, cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, renovascular hypertension, congestive heart failure secondary to myocardial infarction, or aortic insufficiency. Vascular ischemic symptoms with findings of stenosis or occlusion are the hallmarks of the disease.

Table 25.2 lists the ACR criteria for the diagnosis of TA. Delay in diagnosis has been attributed to the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms and the clinical presentation, which may be quite similar to that of patients suffering from atherosclerotic disease. TA should be suspected in any young patient with bruits, atypical distribution of ischemic symptoms (i.e., upper extremities), and age-inappropriate vascular disease (congestive heart failure, aortic aneurysm, myocardial infarction, or aortic insufficiency).

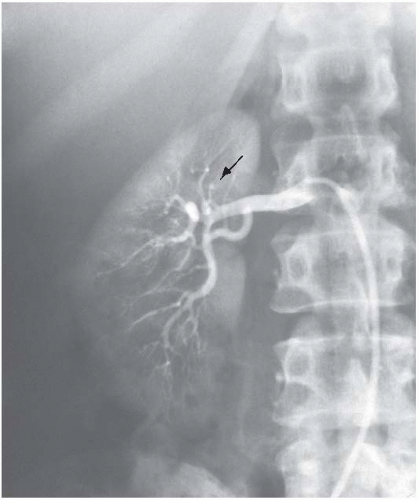

Table 25.3 lists the angiographic classification of TA. This may be helpful in intervention planning if indicated but is of no prognostic significance. Aneurysms are relatively uncommon features of TA in the United States. This is different from the experience in the Far East, where both abdominal and thoracic aortic aneurysms frequently develop as long-term sequelae of TA.

Diagnosis

Acute-phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated in more than 50% of patients with TA. All patients with suspected TA should have blood pressures in four extremities (by Doppler if necessary). Subclavian artery stenosis is very common, and blood pressure in the upper extremities may be unreliable. Renal artery stenosis may produce extreme hypertension, and in the presence of bilateral subclavian disease, this may not be recognized until occurrence of stroke, myocardial infarction, or congestive heart failure. Leg pressures should always be evaluated, renal artery disease should be screened for, and a central pressure should be evaluated if there is any question regarding the reliability of pressure readings.

Confirmation of diagnosis and staging requires comprehensive evaluation of the aorta and its main branches by angiography or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Three-dimensional (3D) contrast-enhanced MRA can be utilized to evaluate anatomy; T2-weighted sequences and double inversion recovery (DIR) (black-blood) sequences can be used to evaluate vessel wall thickening; delayed postgadolinium sequences can be used to assess vessel wall enhancement as a potential sign of inflammation. Positron emission tomography (PET) can also be useful in the evaluation of patients with large cell vasculitis. x-Ray angiography may provide definitive information in diagnostically challenging cases and allows for measurement of central pressure, surgical planning, and/or intervention. CT angiography is also widely used and can provide useful information including the location and severity of stenosis/aneurysm and can provide accurate measurement of the blood vessel wall thickness at least during the initial evaluation. The need for ionizing radiation, particularly in young patients, and use of nephrotoxic contrast limit the use particularly in young women and those with concomitant renovascular disease and consequent renal dysfunction.

Follow-up of patients is frequently quite difficult because of the lack of reliable measures of disease activity, including acute-phase reactants. MR-derived surrogate information, such as vessel wall thickening, along

with 3D MRA may be used in the absence of serum markers. Carotid and renal duplex may be used selectively as adjunctive modalities in the follow-up of patients. The role of intravascular ultrasound in determining disease activity remains to be defined.

Treatment

Glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment in TA with resolution of symptoms in 25 to 100% of the patients. Different regimens of steroids have been advocated in the initial treatment of TA. To date, there have been no comparative trials to determine the optimal dose and length of glucocorticoid regimen. In a retrospective analysis of patients who received an initial dose of 30 mg of prednisone with active arteritis, 51% had an improved quality of life, 37% experienced no change, and 12% worsened. In the largest prospective standardized experience with glucocorticoid in TA, patients received 1 mg/kg/d for the first 1 to 3 months. When disease activity decreased, the prednisone was tapered to an alternate-day schedule and further tapered. In this regimen, initial remission was achieved in 52% of the patients. Although such data support the use of an initial high dose of prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), a lower dose may be selected in individuals at high risk for steroid toxicity in cases where there is no immediate threat of tissue ischemia.

Cytotoxic therapy is considered in patients with TA when there are signs of progressive disease despite the use of adequate glucocorticoid therapy, relapse upon tapering of glucocorticoid, and major organ’s risk or when there is an especially high rate of complications from glucocorticoid therapy. The greatest published experience with cytotoxic medications in TA has been with methotrexate and, to a lesser degree, with cyclophosphamide. Methotrexate may be an effective means of inducing remission and minimizing glucocorticoid toxicity in resistant TA patients.

Empiric adjunctive use of statins has been advocated by virtue of their potential immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been used in retrospective studies, but the potential benefits remain unclear.

Several studies have reported that angioplasty with or without stenting can be used successfully to treat patients with segmental arterial stenosis caused by TA, especially after the acute inflammatory phase has resolved. In the future, drug-coated stents may afford benefits. Surgical revascularization may be required in patients with diffuse disease, but surgical planning must take into consideration the relative likelihood of involvement of the proximal (source) vessel with TA in the future. Vascular tissue samples, to document disease activity, should be obtained whenever possible.

Giant Cell Arteritis of the Elderly

GCA (temporal arteritis, cranial arteritis) is an inflammatory vasculopathy that affects medium and large vessels. Activated macrophages and CD4+ T cells are found in all vessel layers, presumably entering through the vasa-vasorum. Giant cells may or may not be found in the vessel wall.

Epidemiology

GCA is a common form of primary vasculitis in the United States and Europe with incidence rates reaching 15 to 25 cases per 100,000 in persons aged 50 years and older. GCA is uncommon in Southern Europeans (6 cases/100,000) and in African Americans and Hispanics (1 or 2 cases/100,000). GCA typically affects patients older than 50 years of age with a mean age of 70 years. The female:male ratio is 2:1.

Clinical Features

GCA may present with various signs and symptoms.

Table 25.4 lists some of the clinical features in GCA. Constitutional symptoms are frequent and may be the presenting features. Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a clinical syndrome closely linked to GCA, characterized by the presence of symmetrical proximal aching and morning stiffness due to low-grade proximal synovitis, bursitis, and tenosynovitis. PMR is present in 40% of patients with GCA and may be the only presenting feature; however, most patients with PMR do not have clinical GCA. Headache, usually of sudden onset, is the most frequent symptom of GCA. It is usually localized to the temporal areas but may be frontal, occipital, or more diffuse. Prominent and enlarged temporal arteries and jaw claudication (due to masseter ischemia) constitute relatively specific signs for GCA. Loss of vision is the most feared complication of GCA. It is usually secondary to ischemia of the optic nerve due to arteritis of the branches of the ophthalmic or posterior ciliary arteries and occasionally due to occlusion of the retinal arterioles. The incidence of permanent loss of vision in recent series is about 20%. Stroke and/or transient ischemic attacks are the most common neurological findings and are present in 30% of the cases. Occlusive lesions of large proximal

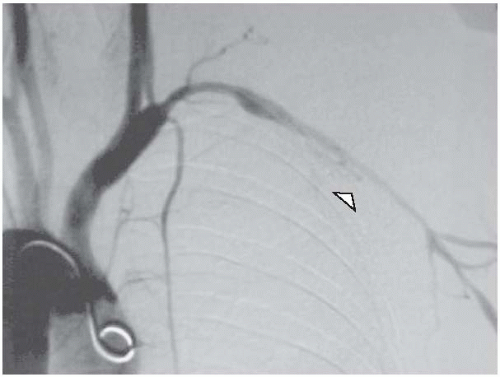

extremity arteries occur in about 15% of the cases (affecting mainly the subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries) and result in arm claudication with reduced pulses (

Fig. 25.2). Patients with GCA are 17.3 times more likely to develop thoracic aneurysms compared to age- and sex-matched normal population.

Patients who present with PMR without symptoms of GCA may have a positive temporal artery biopsy and/or vascular complications including aortic branch stenoses and thoracic aortic aneurysms.

Diagnosis

GCA is usually considered in patients older than 50 years who present with a new headache, abrupt visual loss, or fever of unknown etiology or in patients with PMR who have vascular manifestations as described earlier. Exclusion of atherosclerotic disease of the carotid, aorta, and aortic branches, which can also present with acute loss of vision, and of aortic aneurysm is an essential step in the workup of these patients. The “at-risk” age group for both entities is similar; however, the presence of elevated acute-phase reactants and other features of the disease, including PMR, favor the diagnosis of GCA over atherosclerotic diseases. A normal ESR or CRP level does not exclude the diagnosis of GCA. However, the diagnosis of GCA should be confirmed by temporal artery biopsy and/or angiographic studies when it involves arteries other than the temporal arteries.

Tissue Examination

The superficial temporal artery is the most commonly biopsied artery, and biopsy is a simple procedure performed under local anesthesia. Glucocorticoid therapy may be initiated before performance of the biopsy; even a week of steroid therapy prior to biopsy is not likely to influence the results. The diagnosis of GCA is confirmed by the presence of inflammatory cells in the vessel wall, often with destruction of the inner elastic membrane. Giant cells are not necessary to make the diagnosis. False-negative biopsies occur due to the patchy involvement of the vessel and can be minimized by sampling larger pieces and the contralateral temporal arteries.

Treatment

GCA is exquisitely sensitive to steroids, and prompt initiation markedly reduces the likelihood of vascular complications. Most patients respond to 40 to 60 mg of prednisone once daily. Response within 3 to 5 days is often quoted as a characteristic feature. If patients do not respond to initial therapy of 40 to 60 mg/d, the dose can be temporarily increased by 10 to 20 mg/d.

In patients with immediate threatening symptoms such as visual loss, intravenous pulses of glucocorticoid have been used initially and then switched to oral therapy, although there are no prospective data directly comparing the visual outcome using these two regimens. By contrast, some patients clearly respond to lower initial doses, but currently there are no reliable clinical or laboratory markers available to identify these patients before starting therapy. Furthermore, there is insufficient evidence to support efficacy of immunosuppressive agents other than glucocorticoids in GCA, although this issue has not been thoroughly studied.

After response to initial steroid therapy, dosage can be reduced every 2 weeks by 10% of the daily dose as long as the patient and the laboratory tests are normal. Below the daily dose of 20 mg/d, the length between decrements can be increased to 2 to 4 weeks depending on the patient’s course and an even slower tapering regimen when the dose is below 10 mg/d. A significant number of patients with GCA will not tolerate such tapering without a flare in their disease. Therefore, careful monitoring of clinical and laboratory inflammatory parameters is necessary [ESR, CRP, and interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels, if available]. Decisions on tapering the treatment regimen should take into consideration the inflammatory markers but should rely mainly on the clinical evaluation of the patient, since the former tend to be unreliable later on in the course of the disease. A common relapsing manifestation of GCA is PMR, which may often respond to small incremental doses of steroids. Another potential, yet silent, complication is the development of aortic aneurysms.

Aspirin and statins may be of some benefit as adjunctive therapies as protection against ischemic cardiovascular events. Furthermore, aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of visual loss. Osteoporosis is a major concern in elderly patients on long-term steroids.