Aortic Valve Disease

Brian R. Lindman

Suzanne V. Arnold

High-Yield Concepts

LVOT dimension is a significant source of error when measuring AVA

Make sure the numbers are internally consistent (AVA, gradients, LVEF)

Subvalvular obstruction: Evaluate flow through the LVOT

Low-dose dobutamine test is helpful in patients suspected of having severe AS in the setting of low flow, low gradients

LV size, shape, and function are helpful in determining acute (normal LV size) versus chronic AR (dilated LV)

Key Views

Parasternal long axis—initial screening for AS severity (ability of valve to open, calcification) and AR severity (width of jet, LV dimensions); LVOT measurement

Parasternal short axis—AoV morphology

Apical long axis and apical five-chamber views—quantitative assessment of AS and AR: LVOT and AoV gradients, AR PHT using Doppler

Apical four chamber—LV dimensions and LV function for AR chronicity

TEE—higher resolution views for valve morphology, planimetry for AVA, AR severity

Severity of Aortic Stenosis

See Table 9-1.

Table 9-1 Severity of Aortic Stenosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Severity of Aortic Regurgitation

See Table 9-2.

Table 9-2 Severity of Aortic Regurgitation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anatomy

Leaflets

The normal aortic valve (AoV) is trileaflet.

A bicuspid valve occurs in 1% to 2% of the population, unicuspid and quadricuspid valves are rare. The abnormal leaflet number may cause inherent valvular stenosis and regurgitation.

Annulus

The leaflets form semi-lunar attachments at the annulus forming a “crown”-like interlocking of ventricular and arterial tissue.

They also attach at the sinotubular junction.

Sinuses of Valsalva

As the proximal aortic root meets the left ventricular outlet there are three sinuses that bulge out and form the supporting structure for the corresponding aortic valve leaflets.

The sinuses and corresponding valve leaflet (or cusp) are named according to the origin of the coronary arteries.

Two sinuses give rise to coronary arteries (right and left) while the third, lying immediately adjacent to the mitral valve, does not (non).

Sinotubular junction

The place where the superior portion of the sinuses narrows and joins the proximal tubular portion of the ascending aorta.

Aortic Stenosis

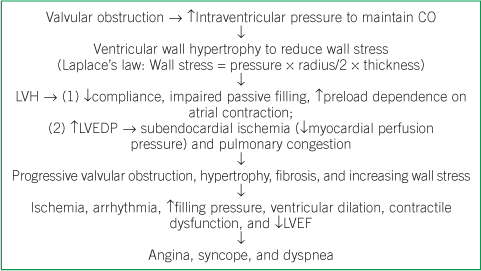

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology for aortic stenosis (AS) involves both the valve and the ventricular adaptation to the stenosis. Within the valve, there is growing evidence for an active biologic process that begins much like the formation of an atherosclerotic plaque and eventually leads to calcified bone formation.

Etiology and morphology

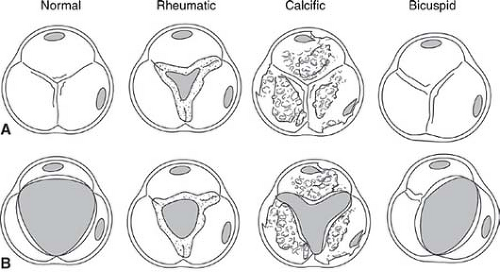

See Table 9-3 and Figure 9-1.

Table 9-3 Etiology and Morphology of Aortic Valve Disease

Etiology

Prevalence, presentation, and associated features

Normal

- Asymptomatic

Calcific/Degenerative

- Most common cause in the United States

- Presents in seventh to ninth decades (mean age mid-70s)

- Risk factors similar to CAD

- Calcification leading to stenosis affects both trileaflet and bicuspid valves

Bicuspid

- 1–2% of population (the most common congenital lesion)

- Presents in sixth to eighth decades (mean age mid-late 60s)

- More prone to endocarditis than trileaflet valves

- Associated with aortopathies (i.e., dissection, aneurysm, coarctation)

Rheumatic

- Most common cause worldwide, much less common in the United States

- Presents in third to fifth decades

- Almost always accompanied by mitral valve involvement

Adapted from Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16(7):777–802, with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 9-1. Typical appearance of aortic valve in diastole (row A) and systole (row B) suggestive of underlying etiology. (Adapted from C. Otto, Principles of Echocardiography, 2007.)

Echocardiographic assessment of AS

2D assessment

Leaflets

Motion of the valve

Aortic valve area (AVA) can be planimetered in the parasternal short-axis view—this is most often only possible in TEE studies using a side-by-side zoomed short-axis 2D image with corresponding color Doppler image to ensure that correct margins are drawn.

Ensure that your visual estimate of valve orifice area corresponds with other measurements; if, for example, the valve appears to open fairly well but measured gradients are considerably higher than you would expect, there may be a supra/subvalvular obstruction. Conversely if the valve appears calcified and stenotic; however, the recorded gradients are lower than expected consider: (1) Doppler acquisition not parallel to flow, (2) low flow, low gradient, reduced LVEF AS, (3) low flow, low gradient, normal LVEF AS (discussed later).

Eccentric closure, doming, and prolapse of the valve in the parasternal long-axis view suggest the presence of a bicuspid valve.

Bicuspid aortic valves (BAVs)—most commonly due to fusion of the right and left coronary cusps (∼80%) or fusion of the right and non-coronary cusps (∼20%); bicuspid valves have an elliptical orifice during systole; they can easily be mistaken for trileaflet valves during diastole, particularly when a raphe is present. Leaflet doming is present because of restricted leaflet motion. Valvular regurgitation is usually highly eccentric and posteriorly directed (Fig. 9-2E). There may be associated aortic abnormalities (dilation of aortic root, coarctation).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree