34 Aortic Stenosis

Nonvalvular obstruction of left ventricular (LV) outflow usually results from a congenital abnormality, such as a membrane, that may exist above or below the valve. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), formerly called idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis, produces a dynamic subaortic obstruction and is the focus of Chapter 19.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

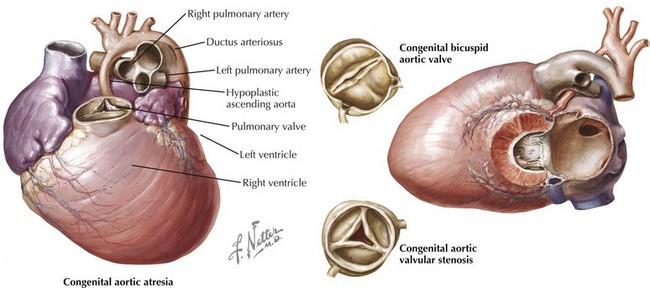

The etiology of valvular aortic stenosis varies with the patient’s age at presentation. In childhood, valvular congenital abnormalities are the usual cause. The aortic valve may be unicuspid, bicuspid, tricuspid, or, rarely, even quadricuspid (Fig. 34-1). Unicuspid valves usually are severely narrowed at birth and produce symptoms in infancy. Bicuspid and malformed tricuspid valves rarely cause symptoms during childhood. More frequently, the abnormal architecture of bicuspid and malformed tricuspid valves alters flow patterns across the valve, slowly traumatizing the leaflets, leading to progressive fibrosis, calcification, and stenosis between ages 40 and 70 years.

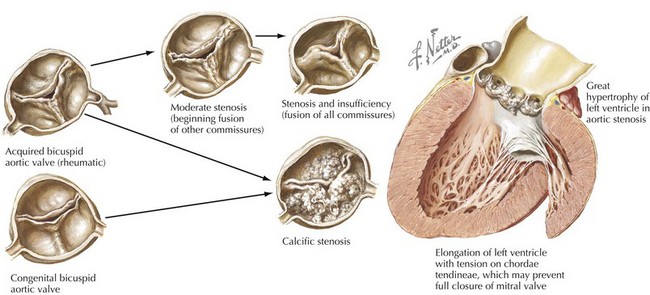

Acquired abnormalities from senile, calcific degeneration of a previously normal valve predominate in patients diagnosed after age 70 years, with a prevalence of 3% to 5% in patients over 75 years old (Fig. 34-2). The pathophysiology of degenerative, calcific aortic stenosis is an area of ongoing investigation. Although it shares some features and risk factors with atherosclerosis (accumulation of atherogenic lipoproteins, evidence of low-density lipoprotein oxidation, inflammation, and microscopic calcification), there are important differences. These include the presence of osteochondrogenic differentiation markers on the surface of valvular endothelial cells, essentially leading to “bone formation” in the valve, as well as a correlation between aortic stenosis and low serum levels of fetuin-A, a serum-based inhibitor of calcification.

Rheumatic involvement of the aortic valve, less prevalent today in the United States than a generation ago, typically results in a combination of stenosis and regurgitation, usually with concomitant mitral valve disease. The rheumatic valve is characterized by commissural fusion and calcification, whereas the more common degenerative aortic stenosis shows calcification progressing from the base of the cusps toward the leaflets, generally sparing the commissures (see Fig. 34-2). Rheumatic aortic stenosis generally presents between ages 30 and 50. Less common causes of aortic stenosis include obstructive vegetations from endocarditis, history of radiation therapy, and rheumatoid involvement with severe nodular thickening of the valve leaflets. Aortic stenosis may also be associated with systemic diseases including Paget’s disease, Fabry’s disease, ochronosis, and end-stage renal disease.

Clinical Presentation

Physical Examination

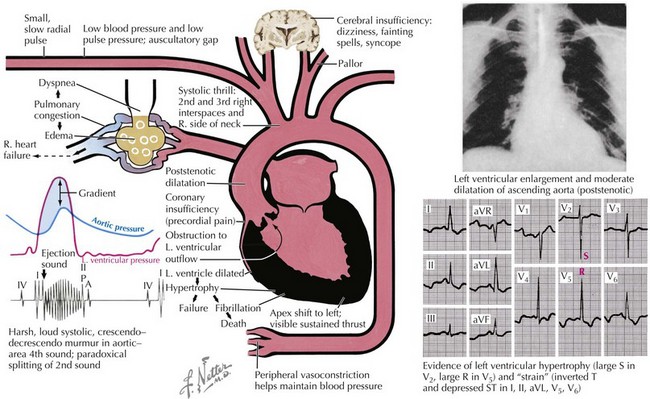

Although noninvasive imaging provides an excellent tool for evaluation of patients with aortic stenosis, this condition can be assessed by a careful physical examination. One of the most notable findings in severe aortic stenosis is a decreased pulsation of the carotid arteries and a slowed arterial upstroke (pulsus parvus et tardus), with the maximum carotid upstroke noticeably delayed after the apical impulse (Fig. 34-3). A marked vibration or shudder may also be felt in the carotid artery. The jugular venous pressure is not elevated unless CHF is present. In mild aortic stenosis the jugular venous pulsations may be unremarkable, whereas late in the disease a prominent “v” wave may occur from tricuspid insufficiency caused by pulmonary hypertension and bulging of the hypertrophied septum into the right ventricle. As the degree of valve stenosis progresses, the LV apical impulse becomes displaced inferiorly and laterally, with a palpable presystolic pulsation (palpable S4). If the apical impulse is hyperdynamic, concomitant aortic or mitral insufficiency should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree