(1)

Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin Ospedale Molinette, Turin, Italy

Abstract

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) arises as a branch of the primitive olfactory artery which originates from the anterior cranial division of the ICA. The ACA develops replacing progressively the primitive olfactory artery which regresses. Later in the evolution from the ACA arises as a secondary branch the MCA (De Vriese 1905; Abbie 1934; Padget 1948; Linn and Kriceff 1974). The adult ACA can be divided into several segments (Huber 1979) (Fig. 4.1):

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) arises as a branch of the primitive olfactory artery which originates from the anterior cranial division of the ICA. The ACA develops replacing progressively the primitive olfactory artery which regresses. Later in the evolution from the ACA arises as a secondary branch the MCA (De Vriese 1905; Abbie 1934; Padget 1948; Linn and Kriceff 1974). The adult ACA can be divided into several segments (Huber 1979) (Fig. 4.1):

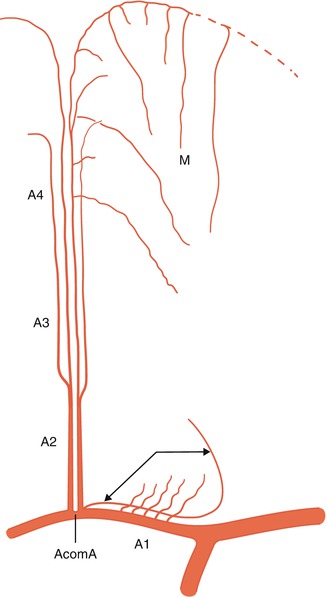

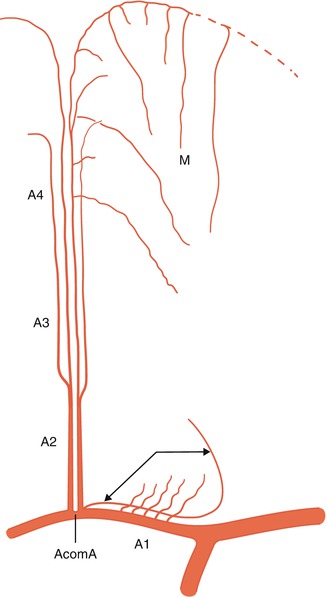

Fig. 4.1

Segments of the anterior cerebral artery: A1, A2, A3, and A4. Deep perforators arising from the A1. Artery of Heubner (double arrow) arising from A1–A2. Medullary arteries (M, short and long branches) arising from cortical branches. Leptomeningeal anastomosis with the MCA (——–)

A1 (precommunicating segment): from its origin to the anterior communicating artery (AcomA)

Distally to the AcomA, the ACA continues as the pericallosal artery

A2 (infracallosal segment)

A3 (precallosal segment)

A4 (supracallosal segment)

4.1 Precommunicating Segment

The first part of the artery is called the A1or precommunicating segment. It arises at the carotid bifurcation, and it runs medially above the chiasma and optic nerve with a horizontal, sometimes descending, ascending, or tortuous course, joining the contralateral A1 by way of the AcomA. Its length is on average 12.7 mm (Perlmutter and Rhoton 1976) (Fig. 4.2).

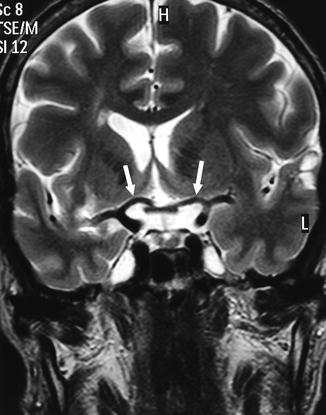

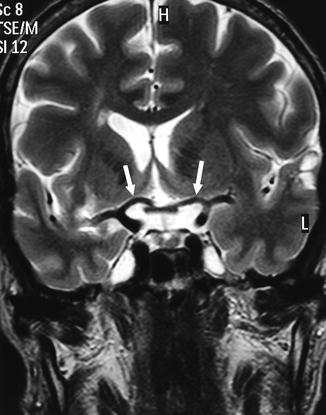

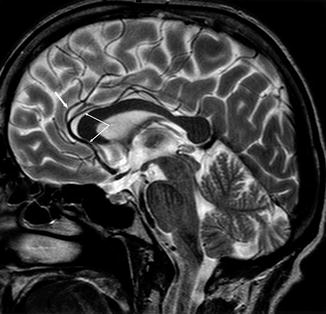

Fig. 4.2

Coronal MRI, T2-weighted image showing the relationship of the A1 to the chiasma (arrows)

Branches. Perforators are found along the length of the A1, but they are more numerous in its proximal section, arising from the superior surface (Dunker and Harris 1976; Perlmutter and Rhoton 1976; Rosner et al. 1984; Mercier et al. 1993). A few perforators also arise from the AcomA (Dunker and Harris 1976; Perlmutter and Rhoton 1976; Rosner et al. 1984; Krayenbühl et al. 1972; Marinković et al. 1990). The perforators enter the anterior medial part of the anterior perforated substance (APS), supplying the suprachiasmatic anterior portion of the hypothalamus. Other perforators supply the optic nerve and chiasma.

The recurrent artery of Heubner, first described by Heubner (1872) and considered by Padget (1948) as an embryological remnant of the primitive olfactory artery, is the largest and longest perforating artery. It commonly takes its origin from the distal A1or proximal A2 segments, rarely from the AcomA. In a few cases, it can have a common origin with the orbitofrontal and frontopolar arteries (Perlmutter and Rhoton 1976; Rosner et al. 1984; Gomes et al. 1984; Tao et al. 2006).

In its course, the artery of Heubner runs back parallel to the A1 and M1 segments to enter the APS anterior to the other perforators of the A1. It can occur as a single or sometimes multiple branches, supplying the inferior part of the head of the nucleus caudatus, the inferior part of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, and adjacent part of the globus pallidus and putamen (Perlmutter and Rhoton 1976; Rosner et al. 1984) (Figs. 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.9, 4.10a–d, 4.12, 5.14 and 11.11).

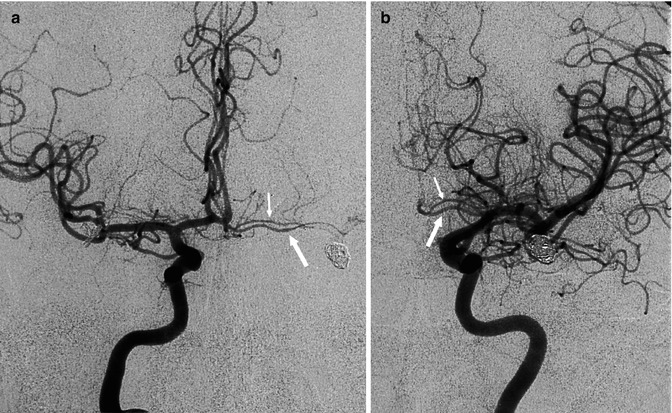

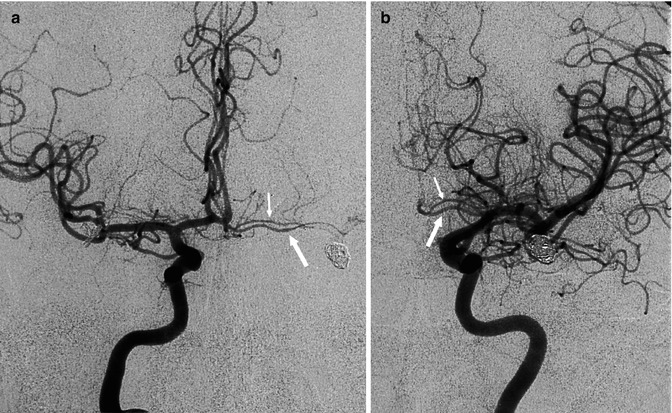

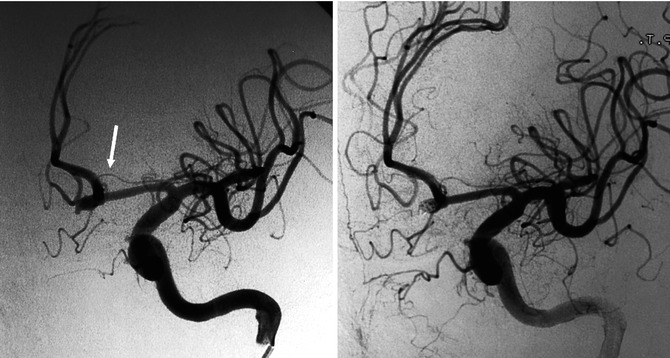

Fig. 4.3

Right (a) – left (b) AP carotid angiogram in a patient treated with coils for a ruptured left middle cerebral artery aneurysm. Well-developed A1 on the right. Hypoplastic left A1 segment (large white arrow). Artery of Heubner (small white arrow) running parallel to the A1 segment

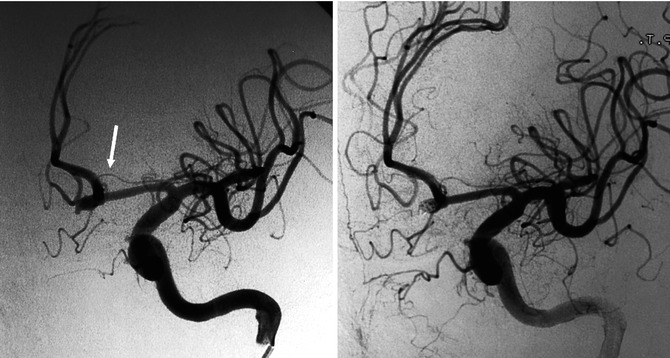

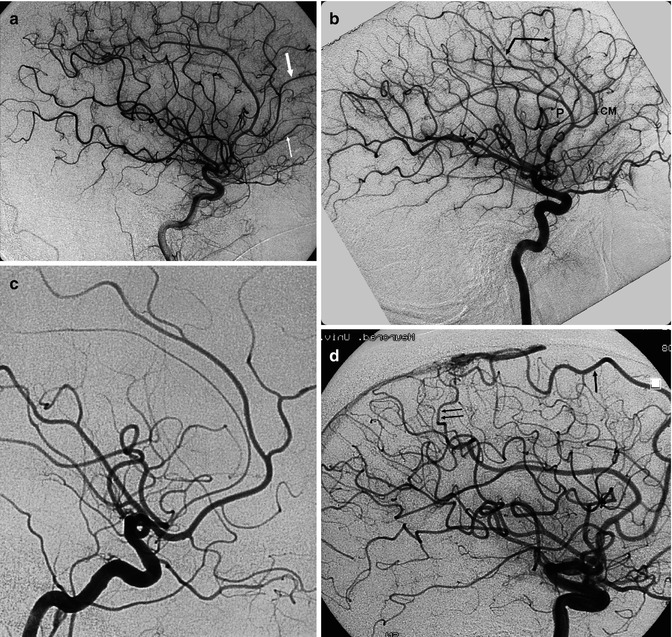

Fig. 4.4

Carotid angiogram, oblique view in a patient examined for ruptured aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery treated in the same section with coils. Left, artery of Heubner (white arrow) arising close to the aneurysm

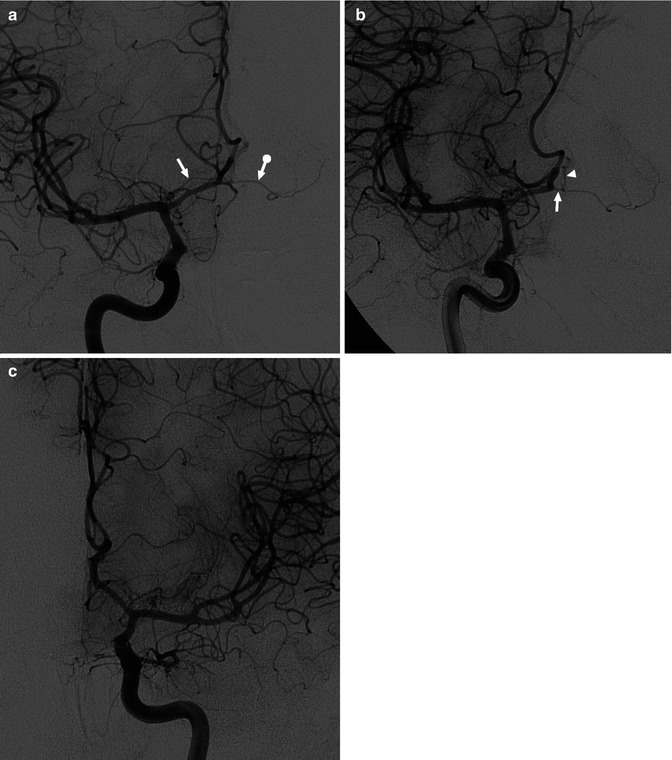

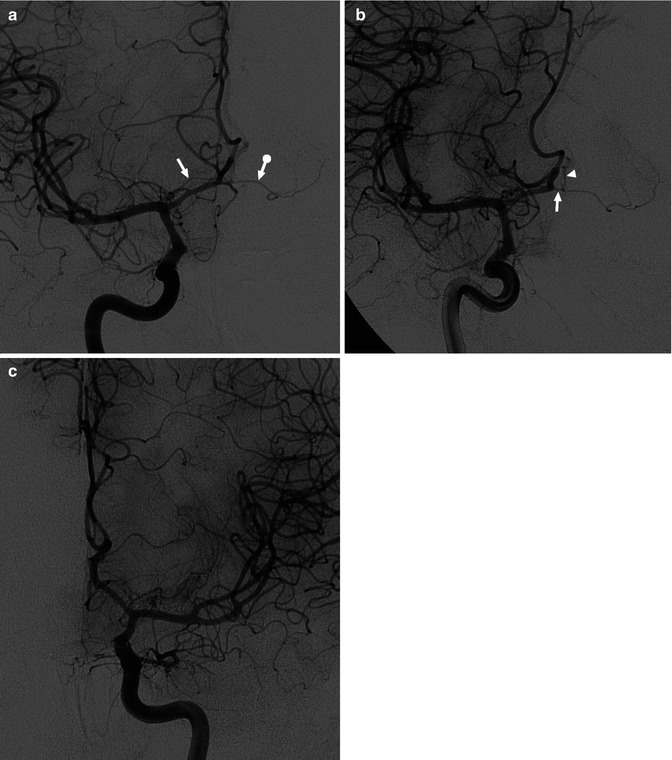

Fig. 4.5

Patient with a meningioma of the planum sphenoidale. Bilateral carotid angiogram. AP view. Typical shifting of both A1. (a) On the right carotid angiogram, the right (arrow) and the left (arrow with dot) arteries of Heubner are clearly recognizable. That on the left arises from the proximal left A2. (b) On the oblique view the origin of the left Heubner artery (arrow) is better shown. There is a faint injection of the left A2 segment (arrow head). (c) Left carotid angiogram. The left Heubner artery is more difficult to identify

The AcomA and the A1–A2 junction are typical sites of aneurysm, which can have a close relationship with the artery of Heubner. When surgical or endovascular treatment is planned, it is very useful to attempt to identify this artery on the angiogram.

4.2 Distal Segments

Distal to the junction with the AcomA begins the segment called the pericallosal artery, which can be divided, according to its relationship with the corpus callosum, into three further segments (Linn and Kriceff 1974; Huber 1979).

4.2.1 Infracallosal Segment

This is also called the A2, and it runs into the interhemispheric fissure upward in front of the lamina terminalis to the genu of the corpus callosum. It gives off infraorbital and frontopolar branches, supplying, respectively, the frontobasal region (gyrus rectus, orbital gyri, olfactory bulb and tract) and the anterior medial part of the superior frontal gyrus (Figs. 4.6 and 4.7).

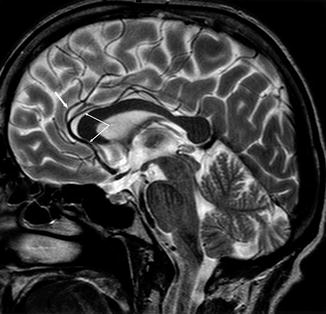

Fig. 4.6

T2-weighted sagittal MRI image. Infra-, pre-, and supracallosal segments of the pericallosal artery (arrow with angle). The supracallosal segment runs with an undulating course above the corpus callosum, partially in the pericallosal cistern and partially superior to it. From its precallosal segment arises the callosomarginal artery (arrow)

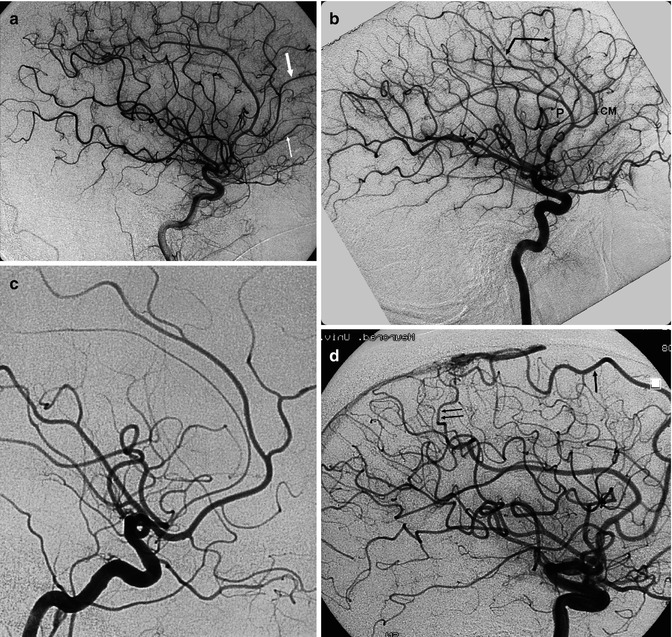

Fig. 4.7

Lateral angiograms. (a) Well-developed callosomarginal artery, though the pericallosal artery is hypoplastic. Fronto-orbital artery (small white arrow) and frontopolar artery (large white arrow). (b) Pericallosal artery (P) in its course along the corpus callosum. Callosomarginal artery (CM) and frontal and parietal branches (arrow with angle). (c) Hypoplastic pericallosal artery and well-developed callosomarginal artery arising as a separate trunk. (d) Well-developed callosomarginal artery (large arrow) supplying small-convexity angiomas. Another branch (double arrow), probably a dilated paracentral artery, arises from the dilated pericallosal artery

4.2.2 Precallosal Segment

This is also called the A3. It is a short segment and curves around the genu of the corpus callosum, to which it gives off small branches (Figs. 4.6 and 4.7). It gives off the callosomarginal artery, which, when well formed, runs posteriorly in the cingulate sulcus above the gyrus cinguli and appears on the lateral angiogram superior and on the anteroposterior view (AP) slightly displaced from the pericallosal artery running on the midline. The more distal branches extend to the paracentral and precuneus lobes.

The callosomarginal artery can be absent or developed only in its frontal portion. In such cases, its branches are replaced by arteries arising from the presupracallosal segment of the pericallosal artery. In other cases it can be predominant and replace completely or partially the pericallosal artery.

4.2.3 Supracallosal Segment

This segment is also called the A4 (Figs. 4.6 and 4.7). It is the more distal segment of the pericallosal artery. It runs posteriorly in the pericallosal cistern, above the surface of the corpus callosum, toward the splenium. Its posterior extent depends on the size of the posterior pericallosal branch (artery of the splenium) of the posterior cerebral artery. Occasionally, it can extend below the corpus callosum toward the foramen of Monro (Kier 1974; Perlmutter and Rhoton 1978) as in the embryological life and anastomoses with the posterior medial choroidal artery (see also Sect. 12.8). The supracallosal artery may have an undulating course and sometimes show an upward distension in its midportion. The artery can be well formed, hypoplastic, or uni- or bilaterally absent.

A meningeal branch can arise from the presupracallosal segment, and this branch supplies the inferior portion of the falx (Lasjaunias and Berenstein 1990). It anastomoses with the branches of the middle meningeal artery, which descend along the falx. The meningeal branch can also be connected with the meningeal branch that arises from the posterior cerebral artery (see Sect. 7.1).

4.2.4 Cortical Branches

Several arteries arise from the supracallosal segment of the pericallosal artery and/or the callosomarginal artery and run on the medial surface of the hemisphere. There is a close relationship between the pericallosal and callosomarginal arteries; when one of these is hypoplastic or absent, the other can replace its vascular territory.

From anterior to posterior, the cortical branches are represented first by the frontal branches. The second artery is the small paracentral branch, which runs toward the paracentral lobule and extends to the central sulcus, supplying the paracentral lobule and superior part of the precentral and postcentral gyri. The more distal arteries are the inferior and superior parietal branches. The superior parietal artery is usually a large branch that runs in the marginal segment of the cingulate sulcus and marks the boundary between the paracentral lobule and precuneus, with branches supplying both lobules (Figs. 4.6 and 4.7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree