Antegrade Aorto-SMA and Celiac Artery Bypass

William J. Quinones-Baldrich

Revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia is indicated in symptomatic patients with appropriate occlusive lesions of at least two of the three mesenteric vessels. On rare occasions, single vessel involvement of the superior mesenteric artery can also present with symptoms in patients with poor collateralization as occurs after prior abdominal surgery particularly stomach or bowel resection. Surgical intervention for patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia is now often reserved for patients who fail or are not suitable candidates for superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and/or celiac angioplasty and stenting. In particular, younger patients who are acceptable risks for surgical repair benefit from a lower recurrence rate and better long-term outcomes with the surgical approach. Patients who present with complete occlusion of the superior mesenteric and/or celiac artery, or longer lesions that extend to the branching portion of these vessels are better treated with surgical intervention. The decision between bypass surgery versus transaortic endarterectomy is based on the extent of occlusive atherosclerotic plaque within the aortic lumen which favors endarterectomy with lesions that extend beyond the vessel origin better treated with bypass surgery.

When mesenteric bypass surgery is recommended, the origin of the reconstruction can be antegrade from the distal descending or supraceliac aorta or retrograde from the infrarenal aorta or common iliac artery. The advantages of an antegrade aortoceliac/SMA reconstruction include origination of the bypass from a usually nondiseased portion of the aorta, a shorter bypass, anatomic forward blood flow with a lower tendency to kink, and less risk of graft enteric adherence with potential erosion or fistula. Patients who require concomitant infrarenal aortic reconstruction to provide inflow for the mesenteric revascularization are better treated with antegrade bypass given the increased risk of combined aortic and mesenteric reconstruction. Longer lesions in the superior mesenteric artery are better treated with an antegrade reconstruction as retrograde revascularization in these instances is more prone to kink and technically more difficult to perform. The main disadvantage of an antegrade mesenteric reconstruction is the need

for supraceliac aortic control for creation of the proximal anastomosis. The risks involved can be minimized with proper patient selection (see “Contraindications”).

for supraceliac aortic control for creation of the proximal anastomosis. The risks involved can be minimized with proper patient selection (see “Contraindications”).

Contraindications

In general, surgical revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia carries higher risks in older patients, patients with chronic renal insufficiency, and those who require concomitant aortic reconstruction. Unless infrarenal aortic reconstruction is indicated for other reasons, patients who would require infrarenal aortic replacement simply to provide inflow for the mesenteric bypass are better treated with an antegrade technique. An absolute contraindication to antegrade mesenteric reconstruction is the presence of substantial calcification in the supraceliac aorta. When plaque is present in the area where the proximal anastomosis is anticipated, there is a significant risk of aortic rupture by the calcified plaque and/or distal embolization during aortic clamping. The degree of calcification can be assessed on the axial views of a CT scan. Minor calcification in the absence of an alternative source of inflow may be acceptable. Moderate or severe calcification represents undue risk and a contraindication to antegrade reconstruction. Similarly, the presence of thrombus in the distal thoracic and supraceliac aorta is a contraindication to cross- or side-clamp the aorta for antegrade mesenteric revascularization.

Relative contraindications to antegrade bypass for chronic mesenteric ischemia include the inability of the patient to tolerate complete or partial supraceliac aortic cross-clamping due to preexisting heart disease. This includes valvular aortic insufficiency, congestive heart failure, and significant untreated coronary artery disease. The presence of aortic valvular disease with insufficiency is of particular concern as increasing resistance from aortic clamping, even when partial, can lead to significant acute ventricular dysfunction. Patients with chronic renal insufficiency have an increased risk of worsening renal function with supraceliac aortic control secondary to decrease renal perfusion. Unfortunately, these patients often have significant aortoiliac occlusive disease and careful judgment is necessary to individualize the recommended technique. If aortoiliac reconstruction is necessary merely to provide adequate inflow for a mesenteric bypass, we prefer an antegrade reconstruction.

Preoperative imaging should include a CT angiogram from the mid-descending thoracic aorta down to the pelvis. Noncontrast images should be reviewed to assess the degree of calcification, if any, particularly in the distal descending and supraceliac aorta. Operative reconstruction for chronic mesenteric ischemia should in all cases attempt to bypass at least the superior mesenteric artery and in most cases both the celiac and superior mesenteric artery. The extent of the lesion in each one of these vessels can be assessed on CT angiography. Many of these patients will have had prior angioplasty and stenting and it is preferable for the distal anastomosis to be located distal to the stented segment. If this is not possible, on rare occasions the stented area can be used provided there is no significant stenosis distal to it (Fig. 12.1). Patency of the celiac bifurcation should be assessed. If patent, the distal anastomosis can be to the splenic or hepatic artery whichever is technically easier. If the celiac bifurcation is occluded, the hepatic artery would be preferred for distal anastomosis as retrograde flow from the splenic may be inadequate. Preoperative angiography is seldom required although in many instances these images are available from prior attempts at endovascular treatment.

Patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia secondary to atherosclerosis will likely be at increased perioperative risk secondary to comorbidities. It is essential to assess these factors and identify those that can be optimized prior to surgery. In particular, significant coronary artery disease should be identified and corrected when partial or complete supraceliac aortic clamping is anticipated. Patients with significant aortic valvular disease, specifically aortic insufficiency, are not good candidates for supraceliac

aortic reconstruction. A preoperative cardiac echocardiogram should be performed to exclude these patients.

aortic reconstruction. A preoperative cardiac echocardiogram should be performed to exclude these patients.

Figure 12.1 Superior mesenteric artery after failed stenting. When the stent extends to the distal SMA, the anastomosis can be performed provided it ends distal to the stent. |

Hypertension should be appropriately controlled prior to surgery and discussions with the anesthesiologist for proper blood pressure control during aortic clamping should take place. We routinely start patients on beta-blockers and a statin prior to aortic surgery. In addition, aspirin is continued or started if the patient is not on an antiplatelet regimen. Clopidogrel is discontinued as in our experience it is associated with a significant increased risk of perioperative bleeding during and after aortic surgery. Patients that are chronically anticoagulated with Coumadin are asked to discontinue the medication 72 hours prior to surgery and depending on the indication for chronic anticoagulation may proceed with the surgery at that time or admitted to the hospital 24 hours before surgery for temporary anticoagulation with heparin.

Preoperative bowel preparation is preferred if the patient can tolerate it. If the patient is unable to tolerate mechanical bowel preparation, an alternative is to keep the patient on clear liquids for at least 48 hours before surgery. Given an anticipated intraoperative period of bowel ischemia, it is best to not have undigested food or bulky stools within the intestine. Type and cross-matching of at least two units of blood is recommended. Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are administered routinely.

Technique: Retroperitoneal Aorto-SMA and Celiac Artery Bypass

A retroperitoneal approach to the supraceliac aorta, celiac and superior mesenteric artery is an excellent alternative if the occlusive process is limited to the first centimeter of the target vessels. These lesions are most often treated in modern practice with angioplasty and stenting. Although the offending lesion may have been limited to the orifice in the proximal portion of the artery in these cases, the presence of the stent will require exposure beyond that segment. Therefore, a retroperitoneal approach from supraceliac to mesenteric bypass is not often possible. It is a good alternative for primary cases selected on the basis of a short proximal occlusion not amenable to endovascular treatment. It is also a good option for patients who have history of prior abdominal surgeries.

We prefer to position the patient for retroperitoneal exposure using a right semilateral decubitus with the left arm on an arm holder. The chest is elevated with the hips as far posterior as possible. The table is hyperextended and the body is supported with a beanbag. The incision is between the 10th and 11th rib and carried towards the midline just below the umbilicus. Every effort is made to maintain the incision within a

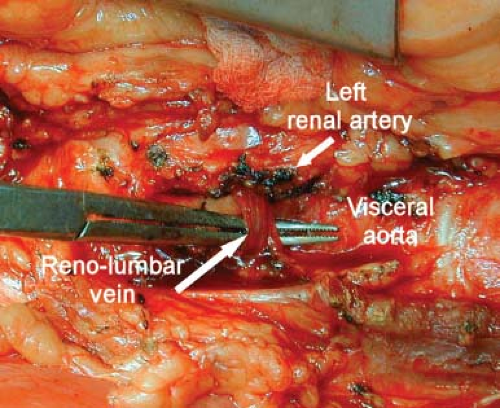

single dermatome. The rectus muscle is preserved dividing the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. Maintaining the incision within a single dermatome and preserving the rectus muscle decreases the incidence of postoperative incision bulge. The peritoneum is separated from the abdominal wall staying anterior to the psoas and separating it from the diaphragm. The incision can be extended proximally which occasionally makes a small entry into the left chest. The diaphragm is not divided. The reno-lumbar vein should be sought, ligated and divided (Fig. 12.2). This is a relatively constant landmark that otherwise would prevent anterior rotation of the left renal vein. The presence of a retro aortic renal vein should also be anticipated during preoperative review of the CT scan. A self-retaining table retractor is essential for adequate exposure. An NG tube is not necessary.

single dermatome. The rectus muscle is preserved dividing the anterior and posterior rectus sheath. Maintaining the incision within a single dermatome and preserving the rectus muscle decreases the incidence of postoperative incision bulge. The peritoneum is separated from the abdominal wall staying anterior to the psoas and separating it from the diaphragm. The incision can be extended proximally which occasionally makes a small entry into the left chest. The diaphragm is not divided. The reno-lumbar vein should be sought, ligated and divided (Fig. 12.2). This is a relatively constant landmark that otherwise would prevent anterior rotation of the left renal vein. The presence of a retro aortic renal vein should also be anticipated during preoperative review of the CT scan. A self-retaining table retractor is essential for adequate exposure. An NG tube is not necessary.

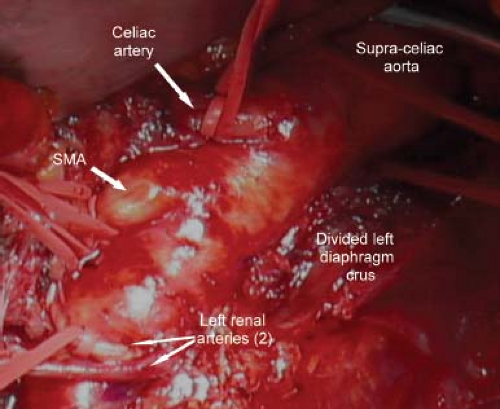

Exposure of the distal descending and supraceliac aorta is performed by division of the diaphragmatic crus (Fig. 12.3). It is necessary to have distance between the celiac origin and the aortic anastomosis of the proximal graft to allow graft control and room to route the graft. Small phrenic arteries are ligated and divided. Intercostal arteries in the chosen aortic segment should be temporarily controlled or ligated if small. The aorta should be encircled with an umbilical tape to assure adequate control. The celiac artery should be exposed to its bifurcation controlling the left gastric, splenic, and hepatic

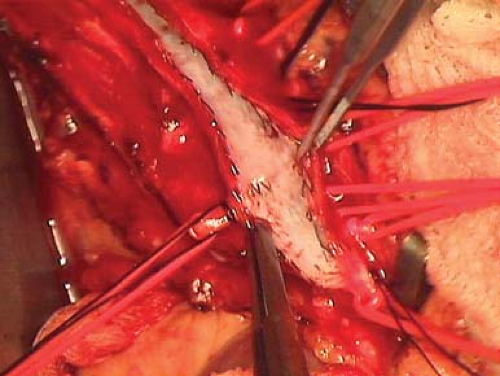

artery individually. The SMA can be exposed to about the takeoff of the middle colic. Further exposure is usually limited by the left renal artery. A 12-6 bifurcated Dacron graft is anastomosed end-to-side to the aorta at least 7 to 10 cm above the celiac origin. This will allow sufficient distance to control the graft for distal anastomosis and facilitates the course of the graft to avoid kinking.

artery individually. The SMA can be exposed to about the takeoff of the middle colic. Further exposure is usually limited by the left renal artery. A 12-6 bifurcated Dacron graft is anastomosed end-to-side to the aorta at least 7 to 10 cm above the celiac origin. This will allow sufficient distance to control the graft for distal anastomosis and facilitates the course of the graft to avoid kinking.

I prefer to perform the celiac anastomosis in an end-to-end fashion given the short length past the offending lesion. Therefore, it is best to control the splenic and hepatic artery individually, ligating the celiac artery at its origin and dividing it proximal to its bifurcation. A continuous 5-0 polypropylene suture is used for anastomosis. The more lateral limb of the bifurcated graft is then anastomosed to the superior mesenteric artery in an end-to-side fashion. Both bypasses are examined by Doppler to assure adequate flow. The viscera are then allowed to return to their anatomic position. We frequently make a small opening in the peritoneum to examine the bowel after it has been derotated. The wound is closed with absorbable monofilament suture, approximating the posterior rectus sheath, internal and transverse muscles in one layer, and the external oblique and anterior rectus sheath as a second layer.

Technique: Transperitoneal Supraceliac Aorta to SMA/Celiac Bypass

Transperitoneal exposure of the supraceliac, celiac, and superior mesenteric artery is the preferred approach for antegrade mesenteric bypass. The patient is positioned supine on the operating table with the back partially hyperextended either with a bump or by flexing the table. An NG tube is inserted to decompress the stomach and maintained postoperatively until the return of bowel function. Although bilateral subcostal incision can give excellent exposure, it involves proximal division of both rectus muscles and abdominal musculature. I prefer a midline incision extended proximally to the xiphoid bone ending just below the umbilicus. This gives excellent exposure to all necessary structures with minimal morbidity. A self-retaining table retractor is essential for adequate exposure.

Once the peritoneal cavity is entered, the bowel is examined to assure viability and absence of any contraindication to prosthetic revascularization. I prefer to expose the superior mesenteric artery first. Retropancreatic exposure of the proximal superior mesenteric artery through the lesser sac by downward retraction of the pancreas has been described. Similarly, the proximal superior mesenteric artery can be exposed by division of the ligament of Treitz, downward retraction of the left renal vein with ligation of the adrenal vein, rotation of the small bowel to the right with visualization of the base of the mesentery, and the takeoff of the superior mesenteric artery. In current practice, these techniques are frequently not appropriate as lesions that require surgical revascularization are longer and require more distal exposure of the target artery. I prefer to expose the mid-superior mesenteric artery at the base of the mesocolon just distal to the takeoff of the middle colic artery (Fig. 12.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree