In a recent editorial in the journal, He et al state that the association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and blood pressure may be mediated, at least in part, by salt intake. We take the issue with several points made by the authors and make a case for quite different conclusions.

The authors state that, “salt is a major drive to thirst”; “an increase in salt intake will increase the amount of fluid consumed, and if part of this fluid is in the form of soft drinks, [sugar] will be increased proportionately.” In other words, salt consumption drives fluid intake, and sugar may just, coincidentally, come along for the ride. We would argue something more akin to the opposite. Sugar consumption leads to insulin spikes, low blood sugar, and hunger. Sugar is a major drive to hunger; an increase in sugar will increase the amount of food consumed, and if part of this food is in the form of processed foods, sodium will be increased proportionately. In other words, sugar consumption drives food intake, and sodium may just, coincidentally, come along for the ride.

Processed foods are the principal source of dietary sodium ; they also happen to be predominant sources of added sugars. Dietary sodium intake tracks with the consumption of added sugars, but it is that sugar, not the salt, that may be the actual causative factor for increased blood pressure. This notion is supported by meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials suggesting that sugar is more strongly related to blood pressure in humans than sodium. Moreover, the fructose component of commonest sugars has been shown to increase blood pressure in a manner independent of sodium intake and salt sensitivity. Encouraging consumers to hold the sugar, not the salt, may be the better dietary strategy to achieve blood pressure control.

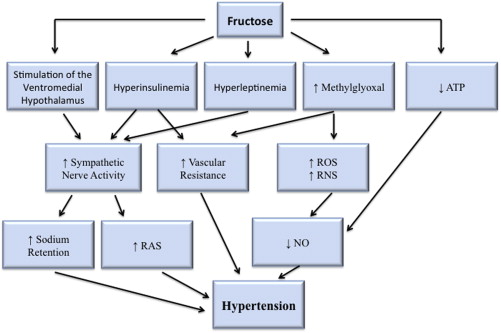

The authors go on to state that “sugar in soft drinks stimulates insulin secretion which could lead to sodium and water retention and, thereby, possibly increasing blood pressure.” Although this might be true, clinical trial data do not support the notion that retention of sodium is clinically significant in regards to increased blood pressure with sugar-sweetened beverages. In a trial of 20 healthy normotensive men, consumption of a sucrose-sweetened beverage led to a significant increase in blood pressure, whereas consumption of a fructose-sweetened beverage did not, although the fructose-sweetened beverage had the greater antinatriuretic effect. What this result suggests is that retention of sodium is not the main mechanism for sugar’s ability to elevate blood pressure. Another, more likely, mechanism is activation of the sympathetic nervous system—both directly through sugar’s effect on the ventromedial hypothalamus and indirectly through hyperinsulinemia—with resultant changes to heart rate and vascular tone. Hyperleptinemia, increased production of methylglyoxal, and reductions in adenosine triphosphate—leading to reductions in nitric oxide—may also play a role ( Figure 1 ). Activation of the sympathetic nervous system by fructose is supported by its ability to increase blood pressure and heart rate in humans on acute ingestion.

He et al conclude that, “A reduction in population salt intake, which can easily be made by slowly reducing the amounts of salt added to foods by the food industry, will lead to a reduction in population blood pressure and cardiovascular mortality, as demonstrated in the UK and Finland.” But such ecological associations hardly prove causation. Data from randomized trials and prospective cohort studies suggest that lowering sodium intake could actually increase mortality for those with diabetes and heart failure (both of which are growing in prevalence in the general population). Moreover, even in healthy subjects, low sodium intake may predispose to insulin resistance, and a meta-analysis implicates low sodium intake in elevating cardiovascular risk through unhealthy lipid and neuroendocrine profiles.

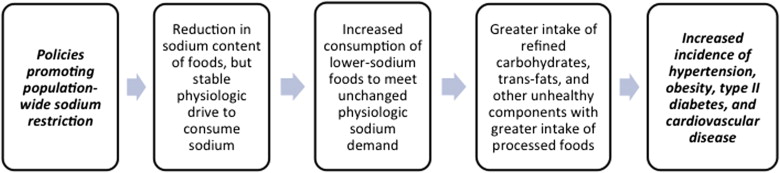

Beyond concerns related to sodium directly, the suggestions by He et al for “reducing the amounts of salt added to foods by the food industry” could have broader unintended consequences for the population in general. Human intake of sodium occurs in a remarkably narrow range across varied populations, suggesting tight physiological regulation. If prepared and processed foods became less salty, it is entirely possible that people would eat more of them to obtain the sodium their physiology demands ( Figure 2 ). Would the concomitant increase in added sugars and other refined carbohydrates, transfats and other processed oils, and chemical colorings, flavorings, and preservatives from the increased consumption of processed foods result in overall benefit for population health?

The investigators state that “a reduction in salt intake will cause a reduction in sugar sweetened soft drink consumption and, thereby, a decrease in obesity and type II diabetes.” We argue the opposite ( Figure 2 ); a reduction in salt intake may lead to an increased intake in processed foods (and added sugars) and, thereby, increase the risk of diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. We do, however, agree with the authors that, “efforts to reduce soft drink consumption combined with a gradual reduction in the amounts of sugar added to soft drinks will provide additional beneficial effects on health.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree