Intermediate Coronary Lesions

Angiographers commonly encounter lesions that elude accurate determination of their severity despite using multiple radiographic projections. Vessel overlapping, vessel tortuosity, eccentric lesions, ostial or bifurcation lesions, and severe calcification constitute the major reasons for suboptimal angiographic visualization of the lumen. This is particularly important when the lesions are of intermediate (40% to 70%) severity in patients whose symptomatic status is difficult to evaluate. For these ambiguous lesions, IVUS provides a tomographic perspective, independent of the radiographic projection and often permits plaque and lumen quantification. Further, it allows the determination of plaque morphology, which can aid in the assessment of the clinical significance of a lesion.

When an intermediate lesion is encountered, further assessment of the lesion can be accomplished either by functional assessment using pressure or flow measurements or by morphologic delineation using IVUS. Measurements of fractional flow reserve (FFR) and coronary velocity flow reserve (CVFR) have been proven useful in identifying lesions of hemodynamic significance, based on cut-off values that achieve clinically adequate sensitivity and specificity (

4,

5). The use of IVUS is preferred if the anatomical distribution (e.g., involvement of ostium or bifurcation) or morphology of the lesion (e.g., ulceration versus calcification as the cause of haziness) is critical for decision making. Therefore, IVUS interrogation of the intermediate lesion should include careful measurements and detailed assessment of the morphology of the lesion.

The cut-off values for IVUS measurements that identify hemodynamically significant lesions have been mostly determined by comparing the lumen dimensions with functional studies such as fractional flow reserve (FFR). However, clinical outcome data for these IVUS measurements have been validated only in small retrospective studies. On the other

hand, the FFR data have been prospectively validated and suggest that deferring intermediate-severity lesions that are hemodynamically insignificant by FFR has a favorable clinical follow-up (

6). A study of 51 lesions (not involving the left main coronary artery) in 42 patients found that using IVUS, a minimal luminal area of <3 mm

2 and a lumen area stenosis (lumen area at lesion site divided by lumen area at reference site) of >60% best predicted a hemodynamically significant lesion by FFR (

7). In another study of 53 lesions in 43 patients, a minimal luminal diameter of <1.8 mm, a minimal luminal area of <4 mm

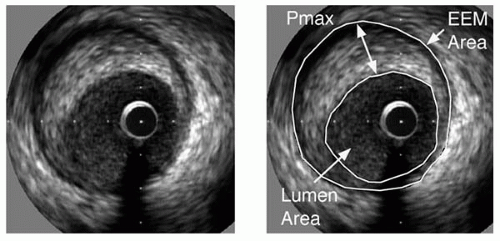

2, and a cross-sectional area stenosis (plaque area divided by external elastic membrane area;

Fig. 5B.1) of >70% have been found to be indicators of hemodynamically significant lesions (

8). Important methodological differences are present in the measurements of FFR in these two studies (use of intracoronary adenosine versus papaverine for the generation of hyperemia), which may explain the discrepant cut-off values. Clinical follow-up data are available for the minimum lumen area of ≥4.0 mm

2, where it has been shown that, in these lesions, the event rate on >1 year follow-up was acceptably low (

9).

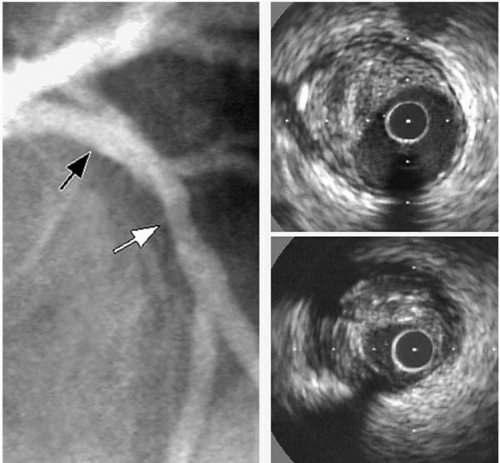

A combination of the IVUS criteria may increase the specificity for determining hemodynamic significance (

8). An example of the utility of IVUS for evaluating an intermediate lesion is shown in

Figure 5B.2. A better understanding of the disease severity and plaque morphology by using IVUS has been found to change the management strategy in more than 20% of the examinations performed immediately prior to coronary intervention in two large series (

10,

11). In both studies, however, the selection of patients for ultrasound examination may have resulted in an overestimation of the true impact of ultrasound imaging on clinical decision making.

Evaluation of the Left Main Coronary Artery

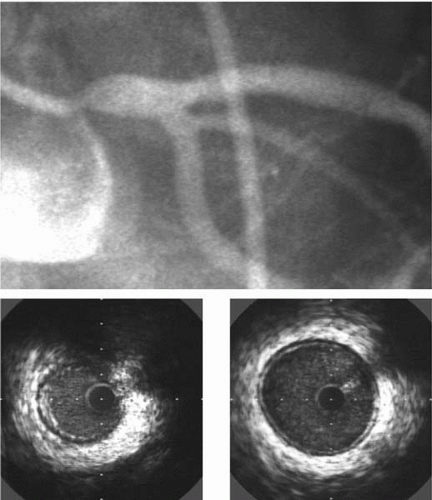

Angiographic quantification of the severity of left main coronary artery (LMCA) obstruction represents a particularly vexing clinical problem (

Fig. 5B.3) (

12). At times, contrast in the aortic cusp obscures the ostium, requiring the operator to engage the vessel with the angiographic catheter and depend on the “reflux” of contrast to visualize the proximal vessel. Occasionally, the left main trunk is very short, which may leave no normal segment to utilize for referencing. “Streaming” of contrast material from the injection vortex also may result in an impression of luminal narrowing. Furthermore, the bifurcation or trifurcation into daughter branches may conceal the distal left main trunk. Therefore, it is not surprising that the reproducibility of quantitative coronary angiography of the LMCA is worse than those of all other coronary arterial segments (

13). Accordingly, IVUS imaging is commonly employed to quantify left main coronary lesions when angiographic interpretation is uncertain.

The imaging of the LMCA using IVUS must be performed carefully for proper measurements. Typically, the IVUS probe is placed in the straighter distal vessel (commonly LAD) and then the guide catheter is disengaged, keeping the catheter coaxial to the LMCA. Selection of the guiding catheter is important to permit coaxial imaging. A short-tip JL-4 guiding catheter tends to provide the ability to withdraw the tip while maintaining the coaxiality in many patients.

Similar to angiography, criteria for the significance of LMCA lesions as assessed by IVUS are different from the rest of the coronary tree. In a recent study of 55 patients with angiographically ambiguous LMCA, a minimal luminal diameter of <2.8 mm and a minimal luminal area of <5.9 mm

2 have been found to predict hemodynamically significant lesions by FFR with high sensitivity and specificity (

14). A single-center study of 122 patients with moderate stenosis (42 ± 16% diameter stenosis by QCA) in the LMCA showed that the minimal luminal diameter of the LMCA was the most important quantitative predictor of cardiac events (death, myocardial infarction, and revascularization) and a minimal luminal diameter of 3 mm performed best as a threshold value (

15). Another study with clinical endpoints suggested that a minimal luminal area of 7.5 mm

2, a value higher than the 5.9 mm

2 dictated by FFR, should be used as the cut-off value for performing revascularization (

16). Because of the different minimal luminal areas proposed as cut-off values, for the time being, it is our preference to use a minimal luminal diameter of about 3 mm as the cut-off value for revascularization for ambiguous LMCA lesions.

Evaluation of Transplant Vasculopathy

The long-term success of cardiac transplantation is limited by transplant vasculopathy (TV), which is the major cause

of death after the first year of transplantation, when the risk of acute cellular rejection and fatal infections subsides. Early TV tends to be clinically silent, and functional testing has low sensitivity for the early process (

17). By the time the disease manifests clinically as heart failure, it is very advanced, and treatment options are limited. The identification of patients at the early stages of TV may provide an opportunity for the prevention of irreversible detrimental effects on the graft survival.

Although coronary angiography is very useful for the diagnosis of nontransplant coronary artery disease, its sensitivity is appreciably less in TV due to the diffuse nature of this disease (

18,

19). IVUS provides a very useful tool to study the development and progression of TV (

20). The routine use of IVUS in this context has been shown to be safe in both the short and long term (

21,

22).

Considering the histologic and IVUS data of normal human coronary artery segments, TV is commonly defined as a site where the intimal thickness is ≥0.5 mm (

23,

24). A grading system also is used by many transplant cardiologists that separates transplant vasculopathy into five classes, in which 0.3 mm is used as a cut-off to diagnose the earlier lesions (

Table 5B.2) (

25).

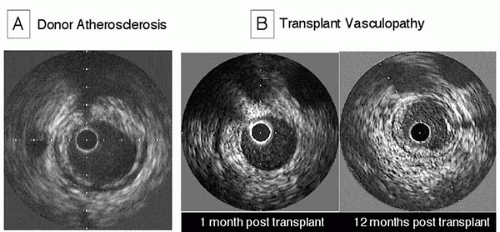

The use of IVUS in the detection of TV can be aided greatly by the inclusion of a baseline IVUS examination soon after transplantation, to separate donor atherosclerotic disease from the new lesions of TV (

Fig. 5B.4). Despite the young donor age, lesions of conventional atherosclerosis are frequently present in donor hearts. In one series with a mean donor age of 32 years, atherosclerotic lesions (maximal intimal thickness ≥0.5 mm) were detectable in more than half of the patients. Donor lesions are more frequently focal and noncircumferential, and they most commonly involve the proximal coronary artery segments (

26). In contrast to donor atherosclerosis, lesions of TV never have calcifications. Although donor disease progression can be detected in nearly half the lesions in the first year after transplantation, the progression of donor lesions is usually insignificant in the second year and thereafter (

26). Importantly, the presence of donor atherosclerosis does not seem to predispose to development of TV (

27,

28).

As opposed to the paucity of studies on the prognostic value of IVUS imaging in native coronary artery disease, several ultrasound studies have demonstrated an association between the severity of disease as assessed by IVUS and the clinical outcome in heart transplant recipients. In a serial study, rapidly progressive vasculopathy documented using IVUS, defined as a ≥0.5 mm increase in intimal thickness within the first year after transplantation, was a powerful predictor of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), and angiographic abnormalities (

29). Other cross-sectional studies have shown similar findings. In one study, patients with an intimal thickening of >0.5 mm were more likely to have cardiac events (sudden death, MI, revascularization) during a follow-up period of 4 years (

30). Another study showed an increased overall mortality and cardiac event rate in patients with mean intimal thickness of >0.3 mm (relative risk for overall mortality = 4.7,

p = 0.01), regardless of the presence of angiographic disease (

31).

In addition to its diagnostic and prognostic value, IVUS also is a sensitive tool to evaluate the effectiveness of various therapies influencing TV. The beneficial effects of pravastatin (

32), diltiazem (

33), vitamins C and E (

34), and everolimus (

35) in transplant vasculopathy have been shown using IVUS imaging, as well as with clinical endpoints.