Fig. 9.1

Pharyngeal anatomy. Sagittal view of pharynx divided into (1) nasopharynx, (2) oropharynx, and (3) hypopharynx (From Nemec SF, Krestan CR, Noebauer-Huhmann IM, et al. Radiologische Normalanatomie des Larynx und Pharynx sowie bildgebende Techniken. Der Radiologe. 2009;49(1):8–16.) (Reprinted with kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media)

Examination of the oropharynx is a prerequisite to performing procedures of the airways. Commonly, the Mallampati classification is used to identify the amount of opening of the oropharynx. The open mouth is examined with the head in neutral position and the tongue protruded. The distance between the base of the tongue to the uvula, soft palate, and pharyngeal pillars is rated:

Class I: uvula, soft palate, and pharyngeal pillars are easily visible.

Class II: soft palate and pharyngeal pillars are visible.

Class III: soft palate alone is visible.

Class IV: only hard palate is visible.

In addition to examining the oropharynx, the opening of the mouth and thyromental distance (distance from the mandibular mentum to the superior thyroid notch during neck extension) should be assessed. A mouth opening of <2 finger widths and a thyromental distance <3 finger widths is suggestive of a difficult airway. A cooperative patient should be able to touch chin to chest, hyperextend the neck, and turn the head from side to side without pain or paresthesia. Cervicooccipital extension of less than a 160 ° angle at the hyoid bone limits proper positioning of the mouth and pharynx to visualize the glottis for endotracheal tube placement. A careful assessment of the mouth should also include evaluation for any prominent or protruding teeth which may block the view of the glottis. Although none of these parameters can singly predict a difficult airway, a careful overall assessment of the oral cavity is a prerequisite in the preparation of a procedure.

Hypopharynx

The hypopharynx lies inferior to the oropharnx. It is surrounded by three constrictor muscles and three inner longitudinal muscles that are responsible for swallowing. Traumatic intubations may lead to complications resulting in dysfunctional swallowing. This area, innervated by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves, contains the piriform recess, postcricoid region, and the posterior pharyngeal wall. The piriform recess is where the tip of the laryngoscope blade rests during intubation. The hypopharynx extends from the epiglottis to the level of cricoid cartilage, and then continues posterior to turn into the esophagus. During swallowing, the hypopharynx facilitates the food bolus into the upper digestive tract.

Larynx

The larynx is responsible for many functions such as phonation and respiration. The most important function, however, is to prevent aspirations.

Laryngeal Anatomy

The larynx is located at the level of the third to sixth cervical spine and inferior to the hyoid bone and superior to the trachea. In women and children, it is situated higher. The laryngeal apparatus is composed of mucosal folds, cartilages, muscles, and their respective neural innervations.

Mucosal Folds

The laryngeal mucosa is mostly lined with squamous and ciliated columnar epithelium. The vocal folds, posterior surface of the epiglottis, the aryepiglottic folds, and the posterior commissure are lined with squamous cell mucosa, while the rest of the laryngeal apparatus is lined with ciliated columnar epithelium. On coronal view (Fig. 9.2), there are twofolds above the vocal folds; the paired aryepiglottic folds superiorly and the paired vestibular folds (structurally seen as false vocal folds) inferiorly. These supraglottic folds outline the vestibule. Below the vestibular folds are small cavities termed the ventricles that are bounded inferiorly by the vocal folds.

Fig. 9.2

Coronal view of the laryngeal apparatus

The Cartilaginous Framework of the Larynx

The structural skeleton framework of the larynx is composed of nine cartilages, along with their connecting membranes and ligaments. The three unpaired cartilages include the thyroid, cricoid, and the epiglottis, and the three paired cartilages are the arytenoids, corniculates, and cuneiforms.

The thyroid cartilage provides support for soft tissue structures. It is made of hyaline cartilage and consists of a pair of laminae that fuse inferiorly at an angle of 90 ° in men and 120 ° in women. Due to the sharper angle of fusion in men, the projection is much more prominent anteriorly and is commonly called the “Adam’s Apple.” The thyroid cartilage articulates with the cricoid cartilage on the medial surface and is further attached by the cricothyroid membrane. This thin membrane is near the surface of the skin, relatively avascular, and serves as the landmark for an emergent cricothyroidotomy. On the external lateral surfaces, there are ridges connecting the extrinsic laryngeal muscles: the sternothyroid, thyrohyoid, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor. The posterior margin of each thyroid lamina courses both upward and downward as superior and inferior cornua. The two superior horns suspend the larynx from the hyoid bone via lateral thyroid ligaments, and two inferior horns articulate with the cricoid cartilage.

The cricoid cartilage is situated below the thyroid cartilage and is the only complete cartilaginous ring. It is signet-ring-shaped and consists of an anterior arch and quadrilateral laminae posteriorly with superior articulating surfaces for the thyroid cartilage. It is also attached to the thyroid cartilage above by the median cricothyorid ligament and is attached to the first tracheal ring by the cricotracheal ligament.

Anterior cricothyroid pressure was advocated for patients who undergo rapid sequence intubation in order to prevent gastric content aspirations. However, the practice was originally described with small case series. In current practice, cricoid pressure should be practiced with caution as the maneuver has the potential to cause airway obstruction and make endotracheal intubations more difficult.

As described earlier, the cricoid cartilage is an important landmark for emergent cricothyroidotomy to rescue a difficult airway. However, subglottic stenosis can occur due to this procedure or in the cases of prolonged endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy that is performed too high (above first tracheal ring). In case of subglottic stenosis, surgical treatment with circumferential resection is not ideal. Instead, an anterior cricoid split is performed: a vertical anterior resection of the cricoid cartilage from the inferior aspect of the thyroid cartilage to the distal aspect of the stenotic segment. The membranous portion of the cervical trachea is preserved and used as a flap for reconstruction of the posterior cricoid plates.

The epiglottis is an elastic fibrocartilage with the superior free edge distal to the base of the tongue. It is lined with mucous membrane and is attached to the arytenoid cartilages by the aryepiglottic folds laterally on both sides. The anterior aspect of the epiglottis forms the inlet of the larynx.

Radiology of the Larynx

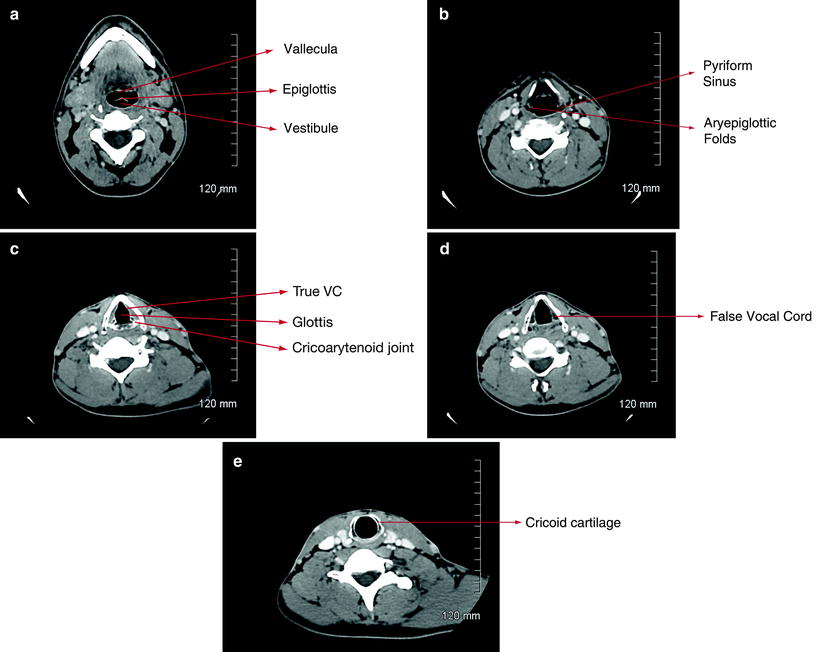

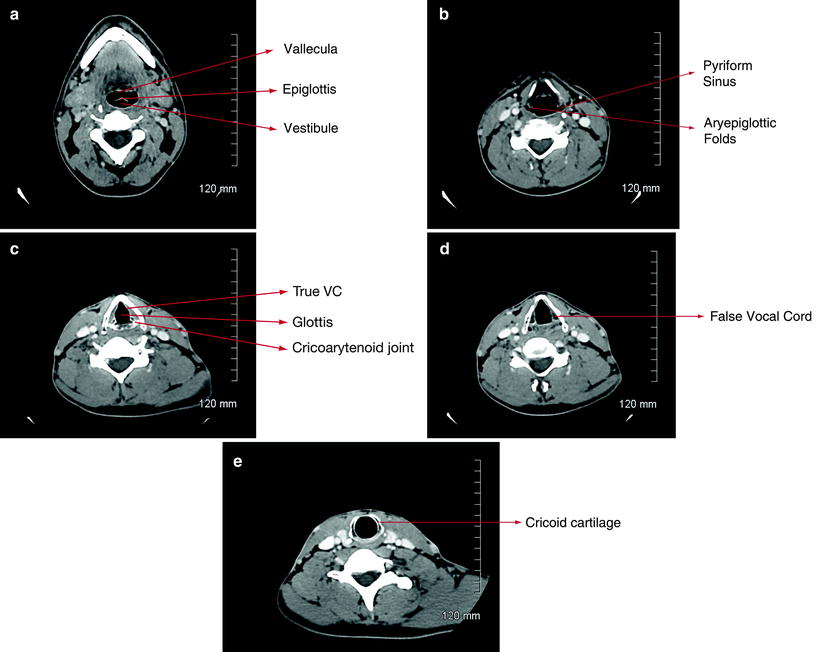

On axial view of computed tomography of the larynx, the epiglottis is seen at the level of the hyoid cartilage and separates the vallecula from the laryngeal vestibule (Figs. 9.2 and 9.3a–e). The valleculae are separated from one another by the glossoepiglottic ligament. Aryepiglottic folds appear at the anterolateral aspect of the larynx and are triangular in shape. They form a border between the laryngeal airway anteriorly and the piriform sinuses posteriorly (Fig. 9.3b). Supraglottic larynx consists of epiglottis, false/ventricular folds, aryepiglottic folds, and the arytenoids. Beneath this level is the glottis which consists of the true vocal folds, including the anterior commissure (Fig. 9.3c). Anterior commissure is the mucosa reflected from the anterior aspect of the true vocal folds, covering the posterior aspect of the thyroid cartilage in the glottis. Superiorly, the glottis is bound by the vocal cord epithelium which turns upward to form the lateral wall of the vestibules. The distinguishing feature between true and false vocal cords is the presence of fat in the false vocal cords (Fig. 9.3d). True vocal folds appear thin and elliptical in shape and are bounded by the thyroid cartilage anteriorly and thyroarytenoid muscles laterally.

Fig. 9.3

Laryngeal CT images. (a) Main carina showing left and right main bronchi. (b) Right upper lobe segments showing typical trifurcation into apical, anterior, and posterior segments. (c) Distal bronchus intermedius showing right middle lobe, right lower lobe segments, and superior segment of the right lower lobes. (d) Distal left main bronchus showing the secondary carina leading to the left upper lobe and left lower lobes. (e) Left lower lobe segments showing the superior segment and the basilar segments

Beneath the glottis is the subglottic region. It is the narrowest part of the airway and is situated between the vocal folds and the upper trachea. The subglottic space is circular in shape and is bounded posteriorly by the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 9.3e).

Muscles

The laryngeal muscles are divided into two groups: extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. The extrinsic group consists of the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles, and they are responsible for elevating and depressing, respectively, the laryngeal apparatus as a unit. The intrinsic muscles control the opening and closing of the glottis, as well as modulating the tension of the vocal cords.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree