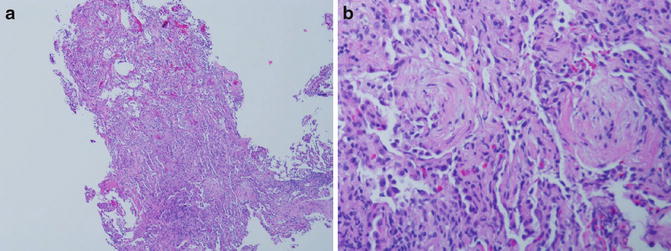

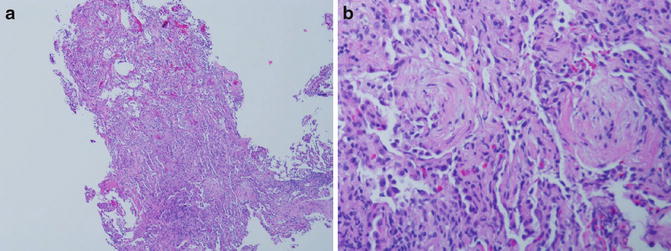

Fig 4.1

Low magnification view of the fibrinopurulent exudate in the alveolar space with thickening of the interalveolar septa in (a). A higher magnification of the same pattern shows the neutrophilic infiltrate in the alveoli as well as in the interstitium in (b)

On a small biopsy, the presence of acute inflammation and/or necrosis is a fortuitous finding. It tends to be sporadic or focal judging from the autopsy material. Usually, by the time a patient is scheduled for a biopsy, the most common finding is the organizing pneumonia which will be discussed later under the acute lung injury pattern.

Viral pneumonia could present in different ways. Adenovirus infection could be subtle and shows only as dark smudgy nuclei in the alveolar lining or with viral cytopathic effect showing ground-glass nuclei. On the other hand, influenza virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) tend to cause areas of necrosis and some neutrophilic infiltrate similar to that of bacterial pneumonia. The clue to the viral etiology would be based on the presence of viral cytopathic changes with nuclear inclusions in case of the HSV and ground-glass nuclei in the influenza virus. These findings could be present in the background of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and recognizing the viral etiology or other etiologies in general is important in the treatment of these cases. Cytomegalovirus induces only chronic inflammation and is characterized by the enlarged cells with basophilic nuclear inclusions. The virus usually infects alveolar lining cells and endothelial cells.

Acute Lung Injury Pattern

The clinical definition of acute lung injury has evolved over the years. In its latest iteration, it is defined as the ratio of the partial pressure of the arterial oxygen relative to that pressure in inspired air. A ratio of <300 is considered indicative of acute lung injury, and a ratio <200 confirms respiratory failure due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [1].

From the histopathologic point of view, the acute lung injury pattern is one that is predominantly of organizing fibrosis mainly by fibroblastic proliferation and a recent myxoid background. The fibrosis is of the recent type without dense collagen deposition or distortion of lung architecture as would be highlighted by a reticulin stain. The main two entities of this pattern are DAD which is the majority of cases of ARDS. The idiopathic variant of DAD is acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) or Hamman-Rich disease. The other entity is bronchiolitis obliterans/organizing pneumonia (BOOP) with its idiopathic variant called cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) [2]. There is a substantial overlap in the histomorphologic features between BOOP and DAD. In both of these entities, there are commonly:

1.

Thickening of the interalveolar septa with mild chronic inflammatory infiltrate and fibroblastic proliferation. The septa could also demonstrate intercellular edema exaggerating the thickness of the septa and making it appear as a reticular pattern.

2.

Proliferation of type II pneumocytes lining the alveolar spaces.

3.

Proliferation of the fibroblasts forming polypoid and fascicular bundles filling up the alveolar spaces to be called “fibroblastic plugs.” The latter could plug the alveolar air spaces or the bronchial lumens.

The lung will turn into a consolidated mass with sporadic air spaces in predominantly fibroelastic mass comprised by the thick septa and fibroblastic plugs [3]. This in turn hinders gas diffusion and hence results in the shortness of breath and hypoxia when measuring blood gases.

Bronchiolitis Obliterans/Organizing Pneumonia

It is by far the most common pattern seen on a lung biopsy. Several reasons account for that; BOOP could be encountered as a reaction to the primary lung injury. This would include post-infectious pneumonia, inhalational injury, post radiation, aspiration pneumonia, and in the setting of collagen vascular disease. In addition, BOOP could be present around mass lesions in the lung such as tumors or granulomas. In the latter situation, if there is familiarity with imaging finding and if there is suspicion for a mass lesion, it is important to communicate to the clinician that the presence of BOOP could be a nonspecific finding, which does not account for the mass lesion seen on imaging. The other scenario where BOOP can be present is as a minor component of other disease entities such as hypersensitivity pneumonia or nonspecific interstitial pneumonia [4].

Histopathologic Features

BOOP usually appears as polypoid structures bulging into the air spaces in the peribronchial areas with a short stalk embedded in the interstitium (Fig. 4.2a, b). Some fascicles of elongated fibroblasts could be seen extended in parallel to the interalveolar septa. Using collagen stains such as Movatt stain, the highlighted light green color of recent organizing fibrosis pattern appears as a tree of cauliflower extending throughout the lung parenchyma in the area of biopsy [5]. The polypoid masses used to be called “Masson’s bodies.” The interstitial cellular infiltrate is usually comprised by a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and neutrophils (Fig. 4.3a, b ). The presence of lymphoid aggregates or lymphoid follicles with germinal centers should raise the possibility of a more chronic process such as hypersensitivity pneumonia (HP) or collagen vascular disease. The presence of poorly formed granulomas and eosinophils would make the first more likely, and the history and serologic testing would confirm the latter.

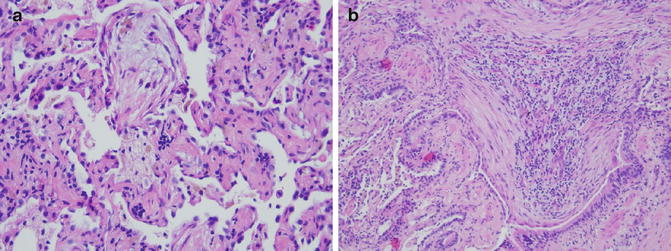

Fig. 4.2

Low power magnification of a small biopsy showing the pale areas with the myxoid fibroblastic plugs and the cellular infiltrate in the thickened interalveolar septa. The air spaces are markedly reduced by the infiltrate (a). The polypoid plug with its stalk is shown with swirling bands of fibroblasts (b)

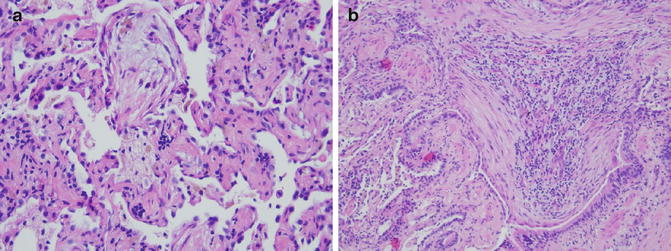

Fig. 4.3

Another example of a polypoid fibroblastic plug filling up the alveolar space (a), and another one is almost obliterating the bronchial lumen (b)

Whereas, in most cases, the histomorphologic features do not provide the underlying etiology of BOOP, it is important to not ignore some of the easily recognizable etiologies. Finding a frothy material in the alveolar space in an immunocompromised patient would suggest Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. In addition, looking for viral inclusions or smudgy nuclei characteristic of adenovirus infection would elicit the causing agent in some cases.

Sometimes, it is difficult to rule out DAD based on a small biopsy, and because of the significant overlap between BOOP and DAD, an umbrella term such as “acute lung injury pattern” may be a useful first step in characterizing the lesion in the lung. DAD usually has an interstitial pattern with less fibroblastic plugs and more fascicles of fibroblasts and of course the hallmark of hyaline membrane. These could be sporadic and not included in the small transbronchial biopsy, but the use of acute lung injury pattern could cover both entities as they share common therapeutic and management pathways.

Another term that is usually confused with BOOP is obliterative bronchiolitis or constrictive bronchiolitis. Many in the lung transplant community refer to it as “bronchiolitis obliterans” which is the opposite of BOOP clinically and histopathologically. Obliterative bronchiolitis most commonly occurs as a late complication of transplant rejection and is mainly a small airway disease. The lung parenchyma is almost normal, and the main problem is the presence of an annular band of fibrosis constricting the lumen of the small airways [6]. Movatt stain is helpful in highlighting the fibrosis.

Idiopathic BOOP is usually a problem on imaging and clinically. As the name suggests, there is no prior incident to suggest the presence of a sole area of consolidation or ground-glass opacity in the lung, and suspicion of malignancy is in the differential diagnosis, especially for adenocarcinoma in situ, which used to be called bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. This particular type was recognized as a separate clinicopathologic entity and given the name COP. However, from the histopathologic standpoint, it is similar in every aspect to BOOP [7].

Diffuse Alveolar Damage and Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome

DAD is characterized by an insidious onset and a rapid course of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation in most cases. In clinical terminology, this is recognized as ARDS. However, there are several etiologies that could result in ARDS but fail to show the characteristic findings of DAD in histopathologic examination. For instance, acute silicosis could result in massive pulmonary edema that results in ARDS, but the pathology of course is not that of DAD. All cases of DAD are considered part of ARDS but not all cases of ARDS would result in DAD. The list of potential causative agents is long and variable. The list includes infection, toxic inhalants, drugs, radiation and chemotherapy, trauma and shock, burns, and certain ingested material like kerosene.

Pathologically, the disease goes through two stages:

Exudative phase: usually in the first week of presentation and is characterized by presence of patchy areas of pulmonary edema and plasma proteins in the alveolar spaces. There are mild or focal areas of thickening of the interalveolar septa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree