Chapter 10 Adverse circulatory effects of exercise

After reading this chapter, you should:

SYNCOPE

In an upright individual, the gravitational field between heart and brain means that cerebral perfusion pressure is always lower than blood pressure at the level of the arterial baroreceptors. In consequence, cerebral perfusion varies more dramatically with variations in cardiac ejection and peripheral resistance than does perfusion to other organs, and situations that result in substantially reduced blood pressure may, in the upright posture, result in fainting (syncope) due to inadequate blood flow to the forebrain.

Causes of syncope

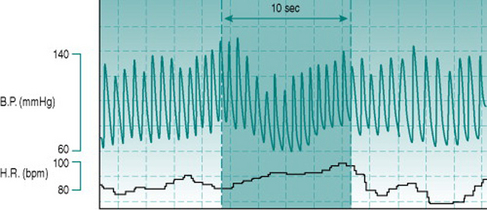

Such reductions in blood pressure could result from reduced venous return and cardiac filling or from reduced baroreflex capacity to induce peripheral vasoconstriction. In the context of exercise, the typical primary effect is obstructed systemic venous return due to elevation of intrathoracic pressure. This pressure increase can be induced voluntarily by forced expiration against a closed glottis and is known as the Valsalva manoeuvre (Fig. 10.1). It occurs naturally during any activity that involves thoracic muscle activation and breath holding, such as carrying heavy suitcases, weight lifting or straining on the lavatory.

All of these additional factors may be associated with athletic performance of specific types. In competitions that involve weight divisions, many performers restrict their fluid intake dramatically in order to make weight, with resulting depletion of plasma volume. Intense, long-term dynamic training has been reported to cause increases in compliance of the large veins, predisposing these athletes to increased venous pooling and to hypotension and fainting during rapid postural change, even in the absence of a Valsalva manoeuvre (Hernandez & Franke 2004). Finally, the elevation of plasma adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) due to the generalized sympathetic discharge associated with central command is enhanced by the additional sympathetic activation due to the stress of competition. Although the cerebral vasculature itself receives only a sparse sympathetic innervation, these circulating catecholamines exert a moderate vasoconstrictor effect on the cerebral precapillary resistance vessels and so reduce brain perfusion at any given level of pressure gradient. An example of Valsalva-induced syncope in a competitive athlete appears in the Case history below.

HYPERTHERMIA

Dependence on evaporative cooling

As discussed in Chapter 9 (p. 106), the internal heat generated by even intense prolonged exercise produces only moderate hyperthermia, so long as there is effective evaporative cooling by sweat. By definition, therefore, anything that interferes with heat loss is likely to result in excessive elevation of body temperature. If this rises to more than 41° C (106° F) then central nervous function begins to be impaired, with permanent brain damage or death occurring at only slightly higher temperatures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree