Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug, with approximately 200 million users worldwide. Once illegal throughout the United States, cannabis is now legal for medicinal purposes in several states and for recreational use in 3 states. The current wave of decriminalization may lead to more widespread use, and it is important that cardiologists be made aware of the potential for marijuana-associated adverse cardiovascular effects that may begin to occur in the population at a greater frequency. In this report, the investigators focus on the known cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral effects of marijuana inhalation. Temporal associations between marijuana use and serious adverse events, including myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, cardiomyopathy, stroke, transient ischemic attack, and cannabis arteritis have been described. In conclusion, the potential for increased use of marijuana in the changing legal landscape suggests the need for the community to intensify research regarding the safety of marijuana use and for cardiologists to maintain an awareness of the potential for adverse effects.

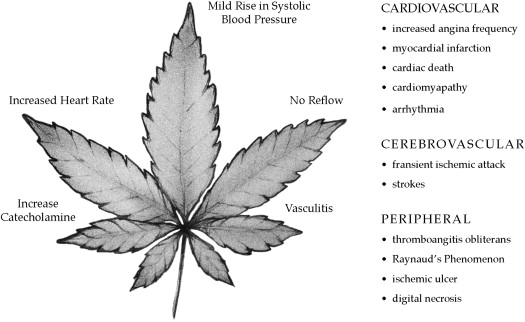

Marijuana is produced by drying the leaves and flowering tops of the cannabis plant and goes by several names, including weed, pot, and ganja. Worldwide, marijuana is among the most widely used illicit drugs. The main active substance in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol, affects cannabinoid receptor 1 in the brain and cannabinoid receptor 2 in the periphery, with predominantly psychoactive effects. Once illegal throughout the United States, marijuana is now legal for medicinal purposes in several states and for recreational use in 3 states (Alaska, Colorado, and Washington). The current wave of decriminalization may lead to more widespread use, and evidence suggests that use in the United States has been steadily increasing since 2007. Although cannabis can be used in several forms, inhalation via smoking is the most common form of marijuana use in the United States and is the focus of this review. There are several well-recognized complications associated with marijuana use, including psychiatric, respiratory system, and cardiovascular disorders. It is therefore important that cardiologists be aware of the potential for marijuana-associated adverse cardiovascular effects, which may begin to occur in the population at a greater frequency. Although noninhalational administration of cannabinoids has been shown to have some beneficial effects on the modulation of atherosclerotic processes in animal models, in this review, we focus on the various adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation in humans ( Figure 1 ).

Cardiovascular Effects of Marijuana Use

Marijuana is more widespread than any other street drug, with an estimated 125 million to 203 million users worldwide, and the potential for adverse cardiovascular effects has been recognized for >40 years. Relatively little is known about its cardiovascular effects or the mechanism underlying such effects. Published reports describe a temporal relation between marijuana use and the development of acute myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, and sudden cardiac death. However, careful evaluation of the cardiovascular effects of marijuana inhalation is complicated by the fact that it is often used in combination with other drugs, such as alcohol or cocaine. Additionally, in many parts of the world, marijuana is smoked in conjunction with tobacco, making it difficult to separate the specific cardiovascular effects of each substance. However, reports of myocardial infarction after exposure to the synthetic cannabinoid K2 suggest that the deleterious effect is likely secondary to cannabinoid exposure rather than 1 of the other nearly 500 chemical components that make up the cannabis plant.

The mechanism underlying the association between marijuana use and myocardial infarction is currently unknown. It is possible that cannabis has a deleterious effect on coronary microcirculation. Rezkalla et al reported a 34-year-old man who developed syncope and ventricular tachycardia after marijuana use. In the electrophysiology laboratory, ventricular tachycardia was inducible. Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries with a significant reduction in coronary flow. After cessation of marijuana, coronary flow reverted to normal, and the patient was no longer inducible in the electrophysiology laboratory. This case suggests a possible effect of marijuana on coronary microcirculation. Other reports describe the phenomenon of slow coronary flow and resulting myocardial infarction.

Marijuana inhalation has been linked to a higher event rate for acute myocardial infarction and an increase in mortality after myocardial infarction. In 2001, Mittleman et al addressed the question by interviewing 3,882 patients with acute myocardial infarctions about marijuana use and found that the risk for developing myocardial infarction was 4.8 times higher than average in the hour immediately after marijuana use. Several case reports describe a similar temporal relation. Most case reports describe relatively young patients in their second or third decades with normal coronary arteries or minimal atherosclerosis, suggesting that marijuana does not lead to the development or acceleration of atherosclerotic damage in healthy adults. Such atypical presentation may explain the paucity of reports on marijuana-associated myocardial infarction despite widespread use of the drug. Marijuana use may also precipitate the development of myocardial infarction in patients with coronary artery disease. After myocardial infarction, mortality is significantly higher in marijuana users than in the general population. In a study of 1,913 adults after hospitalization for myocardial infarction, Mukamal et al found a 4.2-fold increased risk for mortality in marijuana users who reported consuming the drug more than once per week before the onset of the infarction compared with nonusers.

Reports of an association between marijuana use and cardiomyopathy or sudden cardiac death are rarer than those of myocardial infarction. Two case reports describe left ventricular dysfunction associated with marijuana smoking. Similarly, although occasional case reports describe sudden death after marijuana use, most patients were abusing other street drugs, precluding an accurate conclusion about the role of marijuana in causing death. However, Bachs and Mørland reported 6 cases of probable cardiac death in young adults ranging from 17 to 43 years of age that appeared to be related solely to marijuana use. In each case, toxicologic studies revealed only the presence of tetrahydrocannabinol in the blood and urine and no other drugs, and all patients were healthy before sudden death. The rarity of such reports prevents any certainty regarding the potential for direct effects of marijuana on left ventricular function or sudden cardiac death, but the presence of these cases in the published research may be a signal to look for additional cases in the future.

Cerebrovascular Effects of Marijuana Use

Cases of clear, documented stroke during marijuana use have been previously reported. Later reports confirmed this association, finding that strokes tend to occur during actual marijuana inhalation in episodic and heavy marijuana users. Mouzak et al reported classic transient ischemic attacks in 3 patients during marijuana use that resolved with normal full neurologic workup, suggesting a reversible effect of cannabis inhalation on the blood vessels of the brain that may be attributable to a spasm or, less likely, a temporal increase in blood pressure.

Yeung et al postulated that the incidence of stroke related to recreational substance abuse, including marijuana use, is likely underestimated. In 2 studies examining risk factors for stroke in young subjects, marijuana use was found to be an important risk factor for ischemic stroke. In 2012, Singh et al reported a case series including 17 patients with stroke related to cannabis exposure. In 5 patients, reexposure to cannabis resulted in recurrent stroke despite the absence of other vascular risks. There have been 2 additional case reports published describing stroke after myocardial infarction related to heavy marijuana use.

Cerebrovascular Effects of Marijuana Use

Cases of clear, documented stroke during marijuana use have been previously reported. Later reports confirmed this association, finding that strokes tend to occur during actual marijuana inhalation in episodic and heavy marijuana users. Mouzak et al reported classic transient ischemic attacks in 3 patients during marijuana use that resolved with normal full neurologic workup, suggesting a reversible effect of cannabis inhalation on the blood vessels of the brain that may be attributable to a spasm or, less likely, a temporal increase in blood pressure.

Yeung et al postulated that the incidence of stroke related to recreational substance abuse, including marijuana use, is likely underestimated. In 2 studies examining risk factors for stroke in young subjects, marijuana use was found to be an important risk factor for ischemic stroke. In 2012, Singh et al reported a case series including 17 patients with stroke related to cannabis exposure. In 5 patients, reexposure to cannabis resulted in recurrent stroke despite the absence of other vascular risks. There have been 2 additional case reports published describing stroke after myocardial infarction related to heavy marijuana use.

Peripheral Effects of Marijuana Use

Several case reports describe peripheral atherosclerotic disease, known as cannabis arteritis, that is indistinguishable from thromboangiitis obliterans after cannabis consumption. Although some patients inhaled cannabis with tobacco, others used pure marijuana. Martin-Blondel et al reported that even in cases when marijuana use was combined with tobacco use, thromboangiitis obliterans presented earlier in subjects with cannabis exposure. Cannabis arteritis presents with claudication, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and ischemic ulcers or digital necrosis. Angiography usually shows atherosclerotic changes ranging from mild atherosclerotic plaques to total occlusion. Some patients improved with marijuana cessation.

Mechanisms Underlying Adverse Effects of Marijuana Use

Despite the many descriptions of adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular events related to marijuana use, relatively little is known about the underlying mechanisms. In the early 1970s, Beaconsfield et al administered marijuana cigarettes to human volunteers. Within minutes, pulse rate increased from a mean of 66 to 89 beats/min, and systolic blood pressure increased slightly by 5 to 10 mm Hg. Beaconsfield et al also noted an increase in peripheral blood flow consistent with the increase in pulse rate. The consequent increase in heart workload may be responsible for triggering ischemic events. Additionally, although the study was limited, electrocardiographic abnormalities were observed in 5 of 6 subjects, suggesting the possibility of direct cardiac effects.

Several additional mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between marijuana use and adverse cardiovascular effects. For example, Rezkalla et al reported syncope and ventricular tachycardia after marijuana use in a 34-year-old man. In the electrophysiology laboratory, ventricular tachycardia was inducible. Coronary angiography showed normal coronary arteries with a significant reduction in coronary flow. After cessation of marijuana, coronary flow reverted to normal, and the patient was no longer inducible, suggesting a possible effect of marijuana on coronary microcirculation. Other reports describe the phenomenon of slow coronary flow and resulting myocardial infarction.

Several features of marijuana use may explain the potential for an adverse effect on patients with known coronary artery disease. For example, marijuana use is known to increase heart rate and enhance sympathetic tone. The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study showed that patients who used marijuana tended to have a high caloric diet and were more likely to smoke tobacco and use other illicit drugs. In 1997, Gottschalk et al published a randomized, double-blind, crossover study of 10 patients with documented coronary artery disease. They found that smoking marijuana decreased myocardial oxygen delivery, increased myocardial oxygen demand, and decreased the time to develop angina during exercise. A single small study published in 1976 suggests that some of the cardiovascular effects of marijuana may be attenuated by administration of β blockers.

Whether platelets play a role in marijuana-related adverse effects is currently unclear. Dahdouh et al reported the case of a 20-year-old patient who abused tobacco and marijuana and developed cardiac arrest and massive myocardial infarction. Angiography showed a left main artery thrombus with no evidence of underlying atherosclerotic narrowing. Although this may suggest an increase in platelet coagulability related to marijuana use, there is no reason to believe that this may not have been related to heavy smoking alone. Further studies are needed to investigate the effect of marijuana on human platelet function.

Potential mechanisms for sudden cardiac death after marijuana use could be related to the development of acute myocardial infarction and or arrhythmias, the no-reflow phenomenon, or increased catecholamine levels. A single case report supports this notion in describing ectopic atrial rhythm related to cannabis use.

Mechanisms underlying adverse cerebrovascular events may also include cerebral vasoconstriction. Ducros et al reported 9 cases of reversible vasoconstriction syndrome that was associated with marijuana use as the only abused drug. On magnetic resonance imaging, patients showed diffuse or multifocal segmental arterial constriction. Herning et al addressed the same question using transcranial Doppler sonography, finding that marijuana increased vascular resistance and velocity in users compared with nonusers. Although the increased resistance was attenuated with abstinence, it persisted at levels higher than in nonusing controls. These findings suggest that the transient ischemic attacks and strokes seen during marijuana use may be associated with increased cerebral vascular resistance and visible changes in those vessels by magnetic resonance angiography. Peripheral vascular effects may be similar but have not been examined, and studies of the mechanisms underlying marijuana-related adverse events and measures to prevent occurrence or ensure reporting may be warranted in the future.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication for assistance in preparing this report.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

See page 189 for disclosure information.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree