Chapter 6 Acute Stroke

Introduction

A stroke is a sudden change in neurologic function caused by a change in cerebral blood flow. A stroke is also called a brain attack. The public is familiar with the phrase heart attack. Because a stroke happens in the brain rather than in the heart, the phrase brain attack may convey the events involved in a stroke more clearly to the public than the word stroke. The term brain attack and its application to stroke are credited to Vladimir C. Hachinski, M.D., and John Norris, M.D., neurologists from Canada. The National Stroke Association (NSA) began using the term in 1990. The term cerebrovascular accident, a term that was used for many years as a synonym for stroke, has lost favor because strokes are not really accidents.1

Stroke Facts

Classification of Stroke by Anatomic Location

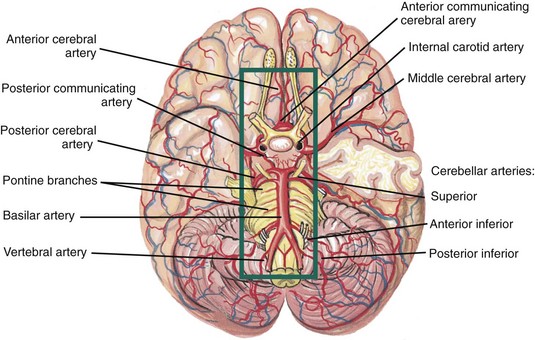

Eighty percent of blood flow to the brain is supplied by the carotid arteries. Twenty percent is supplied through the vertebrobasilar system (Figure 6-1). Strokes involving the carotid arteries are called anterior circulation strokes or carotid territory strokes. They usually involve the cerebral hemispheres. Strokes affecting the vertebrobasilar arteries are called posterior circulation strokes or vertebrobasilar territory strokes. They usually affect the brain stem or cerebellum. Approximately 75% to 80% of ischemic strokes occur in the carotid (or anterior) circulation and 20% to 25% occur in the vertebrobasilar (or posterior) circulation.3 Signs and symptoms of stroke are shown in Table 6-1.

Table 6-1 Signs and Symptoms of Stroke

| Affected Artery | Structures Supplied by Affected Vessel | Signs and Symptoms of Blockage |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior cerebral | Supplies medial surfaces and upper portions of frontal and parietal lobes | |

| Middle cerebral (most commonly blocked vessel in stroke) | Supplies a portion of the frontal lobe, lateral surface of the temporal and parietal lobes, including the primary motor and sensory areas of the face, throat, hand, and arm and in the dominant hemisphere, the areas for speech | |

| Posterior cerebral | Supplies medial and inferior temporal lobes, medial occipital lobe, thalamus, posterior hypothalamus, visual receptive area | |

| Internal carotid | Supplies cerebral hemispheres and diencephalon | |

| Vertebral or basilar | Supplies brainstem and cerebellum |

Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke

Ischemic Stroke

Of the approximately 795,000 strokes that occur each year, about 87% are ischemic, 10% are intracerebral hemorrhage, and 3% are subarachnoid hemorrhage.2,4 About 8% to 12% of ischemic strokes result in death within 30 days.3

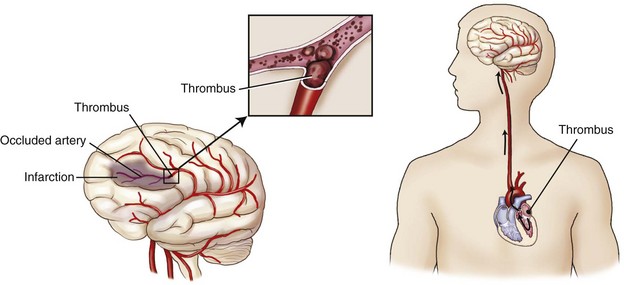

There are two types of ischemic strokes: thrombotic and embolic. It is estimated that about 45% of ischemic strokes are caused by a small (~25%) or large artery (~20%) thrombus, about 20% are embolic in origin (most often from atrial fibrillation),5 and about 30% have an unknown cause.6

A thrombotic stroke is the most common cause of stroke (Figure 6-2). In a thrombotic stroke, atherosclerosis of large vessels in the brain causes progressive narrowing and platelet clumping. Platelet clumping results in the development of blood clots within the brain artery itself (i.e., cerebral thrombosis). When the blood clots are of sufficient size to block blood flow through the artery, the area that was previously supplied by that artery becomes ischemic. Ischemia occurs because the tissue supplied by the blocked artery does not receive oxygen and the essential nutrients needed for normal brain function. The patient’s signs and symptoms depend on the location of the artery affected and the areas of brain ischemia.

ACLS Pearl

About 5% of patients with acute ischemic stroke present with a seizure, and up to 30% have a headache.7

ACLS Pearl

Similar to acute cardiac events, the time of onset of an ischemic stroke has also been shown to have a dominant peak between 6 AM to noon. Even when accounting for stroke patients awakening with symptoms, when the time of onset may not be known, more than 50% of strokes in one study8 and 38% in another9 were thought to have had their onset between 6 AM and noon.10

Evolution of an Ischemic Stroke

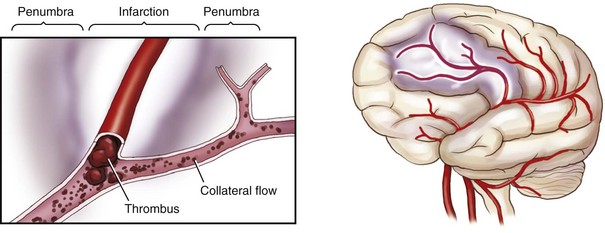

In an ischemic stroke, there are two main areas of injury (Figure 6-3). The first area is the zone of ischemia. Because of the blockage in the artery, there is little blood flow through this area. As a result, brain tissue previously supplied by the blocked vessel is deprived of oxygen, glucose, and other essential nutrients. Unless blood flow is quickly restored, nerve cells and other supporting nervous system cells will be irreversibly damaged or die (i.e., infarct) within a few minutes of the blockage.

The second area of injury is called the ischemic penumbra or the transitional zone. The penumbra is a rim of brain tissue that surrounds the zone of ischemia. It is supplied with blood by collateral arteries that connect with branches of the blocked vessel. The size of the penumbra depends on the number and patency of the collateral arteries. Blood flow to brain tissue in this area is decreased to between 20% and 50% of normal, but not absent. Brain tissue in the penumbra is “stunned” but not yet irreversibly damaged. Because the collateral blood supply is not enough to maintain the brain’s demand for oxygen and glucose indefinitely, brain cells in the penumbra may live or die depending on how quickly blood flow is restored during the early hours of a stroke. Many acute stroke therapies are targeted toward restoring flow or function to the ischemic penumbra.11

A patient may experience warning signs of impending stroke. A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is one of the most important warning signs. A transient ischemic attack has been traditionally defined as a neurologic deficit caused by focal brain ischemia that completely resolves within 24 hours. Most TIAs last only about 5 to 20 minutes.3 This definition has been changed to “a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischemia, with clinical symptoms typically lasting less than one hour, and without evidence of acute infarction.”12 This definition is tissue based rather than time based because some patients with traditionally defined transient ischemic attacks have, in fact, had a stroke.12 Some studies have shown positive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of stroke in up to two thirds of patients with a clinical transient ischemic attack diagnosis. The longer the duration of symptoms, the more likely that the MRI result will be positive.12 A TIA should be treated with the same urgency as a completed stroke.

Reperfusion Therapy

The time from the onset of stroke symptoms to treatment is a key factor to the success of any therapy. The earlier the treatment for stroke is given, the more favorable the results are likely to be. Blood flow needs to be restored to the affected area as quickly as possible. In acute stroke management, the phrase time is brain reflects the need for rapid assessment and intervention because delays in diagnosis and treatment may leave the patient neurologically impaired and disabled.13

Intravenous administration of a recombinant form of tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) has proved to be an effective cerebral reperfusion therapy. Since 1996, the window of opportunity for the use of intravenous rtPA for the treatment of ischemic stroke patients has been within 3 hours of symptom onset. This has required that patients be at a hospital within 60 minutes of symptom onset to be evaluated and receive treatment. Unfortunately, delay in seeking treatment is a common reason for ineligibility for rtPA. Patients not directly seeking medical attention and waiting to see if their symptoms would improve; delays in transfer to a hospital capable of treating the patient; and indeterminate time of symptom onset are among the reasons for treatment delays, precluding the use of rtPA.14,15 The designation of a longer time window for treatment is one of the potential approaches that have been proposed to increase patient treatment opportunities.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

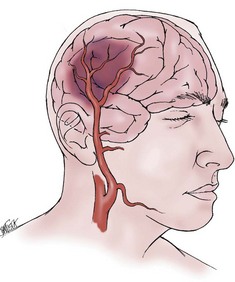

A hemorrhagic stroke is caused by either rupture of an artery with bleeding into the spaces surrounding the brain (i.e., subarachnoid hemorrhage) or bleeding into the brain tissue (i.e., intracerebral hemorrhage) (Figure 6-4). Hemorrhagic strokes can occur in patients of any age. When they occur in young patients, they generally are caused by the rupture of an aneurysm or an arteriovenous malformation. Rarely do these patients have a history of hypertension.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) accounts for about 3% of all strokes.4 A ruptured cerebral aneurysm is the most common cause of SAH. Patients often report a sudden onset “thunderclap” headache or describe the feeling as “the worst headache of my life.” Assessment findings and symptoms may quickly progress to forceful vomiting (often without nausea), neurologic deficits, and visual disturbances (e.g., blurry or double vision), unconsciousness, and seizures. The patient also may show signs and symptoms of rising intracranial pressure, such as unilateral pupil dilation, nausea, vomiting, and vital sign changes.

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) accounts for about 10% of all strokes.4 Most intracerebral hemorrhages are associated with chronic hypertension, but other common causes and risk factors include bleeding disorders, African-American ethnicity, advanced age, vascular malformations, excessive use/abuse of alcohol, and liver dysfunction.16 This type of stroke may require neurosurgery.

You Should Know

Stroke care consists of two phases.16 Phase 1 (emergency or hyperacute phase) encompasses the first 3 to 24 hours after stroke onset and includes prehospital and emergency department care. During this phase, attention is focused on identifying stroke symptoms and location of the infarction, evaluating the patient’s risk for acute and long-term complications, and identifying treatment options. Phase 2 (acute care) encompasses the period 24 to 72 hours after stroke onset. This phase focuses on confirming the cause of stroke and preventing medical complications, preparing the patient and family for discharge, and establishing long-term secondary prevention measures.

Stroke Chain of Survival

[Objective 2]

Like the Chain of Survival used to describe the sequence of events needed to survive sudden cardiac death, the Chain of Recovery is a metaphor for the series of events that must occur during the emergency care of the possible stroke patient to optimize his or her chances of full recovery. The critical links in the chain include:17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree