Chapter 6

Acute Limb Ischaemia

Christos D. Karkos and Thomas E. Kalogirou

5th Department of Surgery, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Hippocratio Hospital, Greece

Introduction

Acute limb ischaemia (ALI) is defined as a sudden decrease in limb perfusion that causes a potential threat to limb viability (manifested by ischaemic rest pain, ulcers and/or gangrene) in patients who present within 2 weeks of the acute event. It is one of the most common emergencies in vascular surgery affecting about 14–16 per 100 000 inhabitants annually. The incidence increases with age and it is seen with equal frequency in men and women. A vascular unit serving a community of half a million can expect to treat approximately 75 such patients each year.

Clinical features

The ‘six P’s’ have been used as a mnemonic to remember the presentation of a patient with ALI (Table 6.1). However, in daily practice, not all of these will necessarily be present in all patients. A subtle clinical picture is not uncommon, reflecting an adequate collateral supply (due to pre-existing atherosclerosis) and the often incomplete nature of the occlusion.

Table 6.1 The six P’s: symptoms and signs of ALI.

| History (three P’s) |

|

| Clinical examination (three P’s) |

|

Pain: It is the most common symptom in ALI and is often severe, continuous and localised in the foot and toes. Its intensity does not reflect the severity of ischaemia. In less severe cases, it may be absent, while in more severe cases, it may decrease with improving collateral perfusion or because sensory loss interferes with perception. Diabetic patients often have a degree of neuropathy and a decreased sensation of pain.

Paraesthesia: It starts as a feeling of numbness and soon progresses to loss of sensation to light touch. This is because thin nerve fibres conducting impulses from light touch are very sensitive to ischaemia and are damaged soon after perfusion is interrupted. In contrast, with pain fibres being less ischaemia-sensitive, finding a decreased pain perception indicates a much later stage of ischaemia.

Paralysis: It can be due to ischaemic damage of either the motor nerves or the muscle itself. In cases of severe proximal ischaemia, the entire limb can become paretic, which may be misinterpreted for a stroke. The inability to dorsiflex and plantarflex the toes is an ominous sign indicating impending necrosis of calf muscles and should prompt immediate revascularisation. Development of firm, spastic musculature (rigour), especially if the contralateral side is normal, indicates extensive muscle necrosis. Attempts to revascularise such a limb are futile.

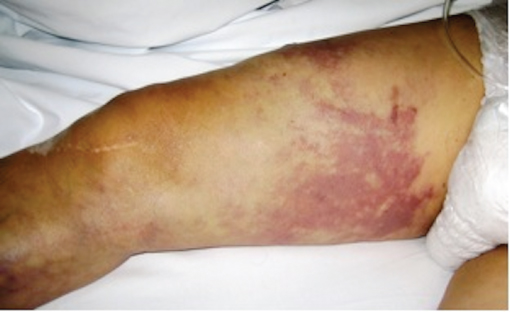

Pallor: Initially, the acutely ischaemic limb is pale (‘marble’ white) due to arterial spasm, but over the next few hours, secondary vasodilatation occurs and blotchy mottled areas of cyanosis develop (representing areas of stagnant blood flow). Failure of the blue blotches to blanch on pressure (fixed mottling) is a sign of capillary bed thrombosis, indicating irreversible ischaemia (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Fixed mottling extending up to the level of the upper thigh and is indicative of irreversible ischaemia and tissue necrosis.

Pulselessness: In general, palpable peripheral pulses exclude severe ischaemia, whereas sudden loss of a previously palpable pulse indicates acute arterial occlusion. Although the prior pulse status of the limb is unlikely to be known, in most cases, the diagnosis can be facilitated by comparing the presence of pulses in the opposite limb.

Perishing cold: Examination will also reveal coldness of the limb about one joint distal to the level of obstruction. The point of occlusion, therefore, can be estimated by the level where the colour and temperature change and the pulse disappears.

The severity of ALI at initial presentation determines the limb outcome and is classified into three categories (Table 6.2).

Table 6.2 Rutherford categories of ALI based on clinical findings and Doppler signals.

| Category | Description and prognosis | Findings | Doppler signals | ||

| Muscle weakness | Sensory loss | Arterial | Venous | ||

| (I) Viable | Not immediately threatened | None | None | Audible (>30 mmHg) | Audible |

| (IIa) Marginally threatened | Salvageable if promptly treated | None | Minimal (toes) or none | Inaudible | Audible |

| (IIb) Immediately threatened | Salvageable with immediate revascularisation | Mild, moderate | More than toes, associated with rest pain | Inaudible | Audible |

| (III) Irreversible | Major tissue loss or permanent tissue damage inevitable | Profound paralysis | Profound, anaesthetic | Inaudible | Inaudible |

Aetiology

The major causes of ALI are (i) embolism, (ii) thrombosis, (iii) occlusion of a vascular graft and (iv) trauma.

Embolism

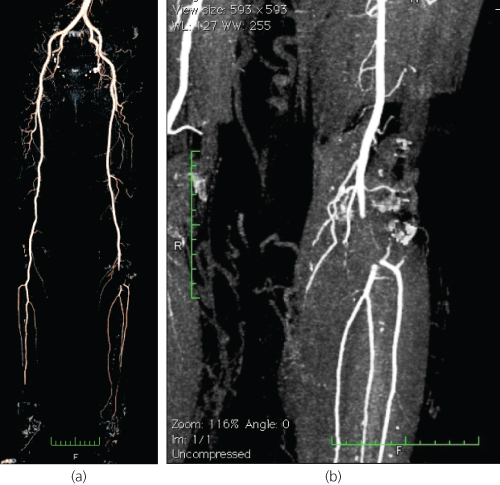

Embolic causes were historically the most common, but with the diminishing prevalence of rheumatic heart disease, they are nowadays responsible for <30–40% of cases. Emboli originate from a proximal source (e.g. the heart or an aneurysm) and lodge at the points of arterial bifurcation, where the vessel diameter decreases abruptly (Figure 6.2), or at points of significant arterial stenoses (in cases of concurrent occlusive disease). The lower limb arteries are affected about five to six times as frequently as those of the upper limb. Embolism usually occurs in the setting of atrial fibrillation or acute myocardial infarction, but other less common cardiac sources also exist (Table 6.3). Frequent non-cardiac causes include peripheral aneurysms or ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques.

Figure 6.2 Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) of a patient with a popliteal artery embolus. (a) The entire arterial tree of both lower limbs looks normal, apart from an abrupt cut-off (filling defect) in the left below-the-knee popliteal artery, which is in keeping with the diagnosis of embolism. (b) The embolus lodged at the point where the artery bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk.

Table 6.3 Causes of embolic occlusion.

| Cardiac causes |

Most common:

Less common:

|

| Non-cardiac causes |

|

| Unknown |

Cholesterol embolisation (atheroembolism) is a particular form of embolism, in which a portion of the plaque breaks off and undergoes embolization to smaller diameter peripheral arteries, such as the digital arteries. In the latter case, one may be faced with the paradox of a patient who has ischaemic toes (or fingers) but palpable distal pulses. This condition is known as trash foot or blue toe syndrome and may occur spontaneously or follow diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, vascular or cardiac surgery. A similar situation can be seen with popliteal (or other peripheral) aneurysms. Occasionally, a cervical rib may compress the subclavian artery (thoracic outlet syndrome), resulting in a post-stenotic dilatation or aneurysm immediately distal to an area of compression and cause emboli in the hand (blue finger).

Thrombosis

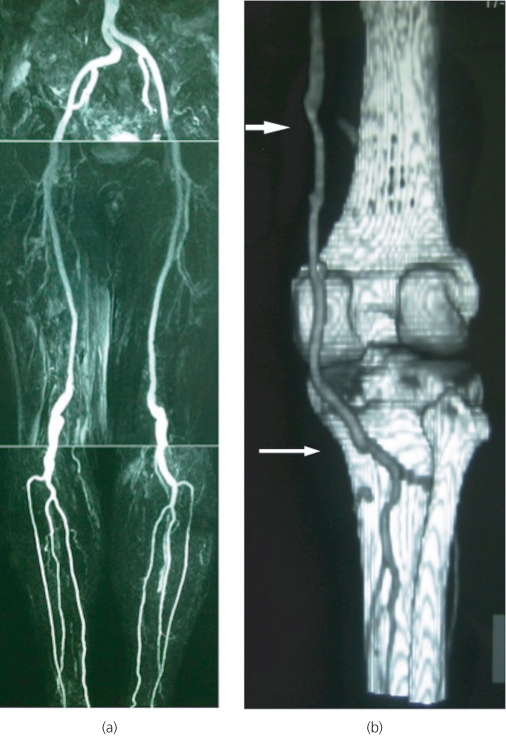

Thrombotic occlusion of native arteries is nowadays the commonest cause of ALI. Thrombosis, as an aetiology for ALI, is a much more diverse category than embolism (Table 6.4). Arterial thrombosis most often develops at the points of severe stenosis, typically of the superficial femoral or popliteal artery. However, a thrombus can be formed in the absence of significant pre-existing stenosis, particularly when the surface of the plaque is ulcerated or after an intraplaque haemorrhage resulting in sudden arterial occlusion. Popliteal aneurysms may also thrombose acutely, a condition that is associated with a high risk of limb loss due to the propagation of thrombus into the crural vessels (Figure 6.3). Other factors leading to thrombosis of a diseased artery (or even of a relatively normal one) are low-flow or hypercoagulable conditions. When faced with a young patient without atherosclerotic risk factors who presents with ALI, the presence of malignancy, hyperviscosity and prothrombotic syndromes should be considered as possible causes, along with anatomical rarities, such as popliteal entrapment or thoracic outlet syndrome.

Table 6.4 Thrombotic causes of ALI.

| Atherosclerotic disease |

| Popliteal and other less common peripheral arterial aneurysms |

| Low-flow conditions (e.g. cardiac failure, immobility, hypovolaemia, hypotension of any cause or decreased blood flow due to a more proximal stenosis) |

| Hypercoagulable states (e.g. myeloproliferative disorders, hyperviscosity syndromes and coagulation disorders) |

| Aortic dissection |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia (occasionally involving the iliac arteries) |

| Cystic adventitial disease (usually affecting the popliteal artery) |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome |

| Popliteal entrapment syndrome |

| Arteritides (e.g. Takayasu’s aortitis and giant cell arteritis) |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans (involving medium-sized muscular arteries) |

| Compartment syndrome |

Figure 6.3 (a) Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of a patient with bilateral popliteal artery aneurysms. (b) Post-operative CTA of another patient who presented with ALI due to a thrombosed right popliteal aneurysm and underwent open surgical repair by means of distal thrombectomy, on-table thrombolysis and interposition bypass with reversed long saphenous vein (white arrows).

Graft occlusion

Prosthetic and venous bypass grafts may occlude for a variety of reasons. Early failures (within the first month) are usually due to technical problems at the time of surgery or poor run-off. Medium-term failures (occurring at around 1 year) are due to intimal hyperplasia at the anastomoses. Vein graft occlusion may also be caused by the development of stenosis within the graft itself (e.g. retained valve cusp of an in situ vein graft or the site of pervious thrombophlebitis). Late failures are usually caused by progression of proximal or distal atherosclerosis.

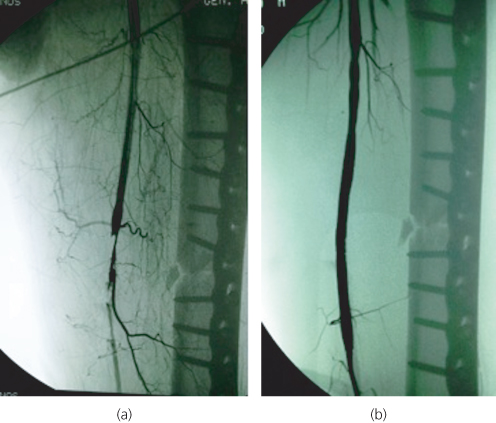

Trauma

Arterial trauma (either blunt or penetrating) is a common cause of ALI. Possible mechanisms include artery transection, intimal disruption or spasm due to a large expanding haematoma. Acute traumatic limb ischaemia may also result from limb fractures and dislocations (Figure 6.4) or be iatrogenic (e.g. percutaneous cardiology and vascular interventions, vascular and orthopaedic limb surgery, general surgical, gynaecological or urological procedures in the pelvis).

Figure 6.4 (a) Intimal disruption of the superficial femoral artery as a result of a femoral shaft fracture. (b) The patient was successfully treated by balloon angioplasty and stent placement.

Management and treatment

Distinguishing embolism from thrombosis, although not always feasible, is desirable because treatment is different (Table 6.5). However, it is the severity of ischaemia that should largely dictate the management. Muscle paralysis, tense swollen fascial compartments and fixed skin staining (i.e. Rutherford category III) characterise the irreversible limb ischaemia, which is, by definition, an indication for primary amputation after appropriate resuscitation and stabilization of the patient. The prevention of limb loss in the Rutherford IIb category (acute white leg with sensorimotor deficit) requires immediate intervention. On the other hand, moderate ALI with acute onset of rest pain with no concomitant paralysis and only mild sensory loss (i.e. Rutherford IIa category) represents the majority of the patients and is often due to acute thrombosis of an atherosclerotic segment. As the limb is not immediately threatened, there is time to plan appropriate intervention with arteriography.

Table 6.5 History and clinical findings pointing towards an embolic cause for ALI.

| Acute onset where the patient is often able to accurately time the moment of the event |

| Prior history of embolism |

| Known embolic source (such as cardiac arrhythmias) |

| No prior history of intermittent claudication |

| Normal pulse and Doppler examination in the unaffected limb |

General measures—conservative treatment

ALI is often the tip of the iceberg of a patient in poor clinical condition with multiple co-morbidities. Many patients suffer from dehydration, cardiac failure, hypoxia and pain that should be managed in the standard way. Urgent venous access, pain relief, oxygen, rehydration and intravenously given heparin (5000 units) may help in stabilizing the patient and limit propagation of thrombus.

Surgery

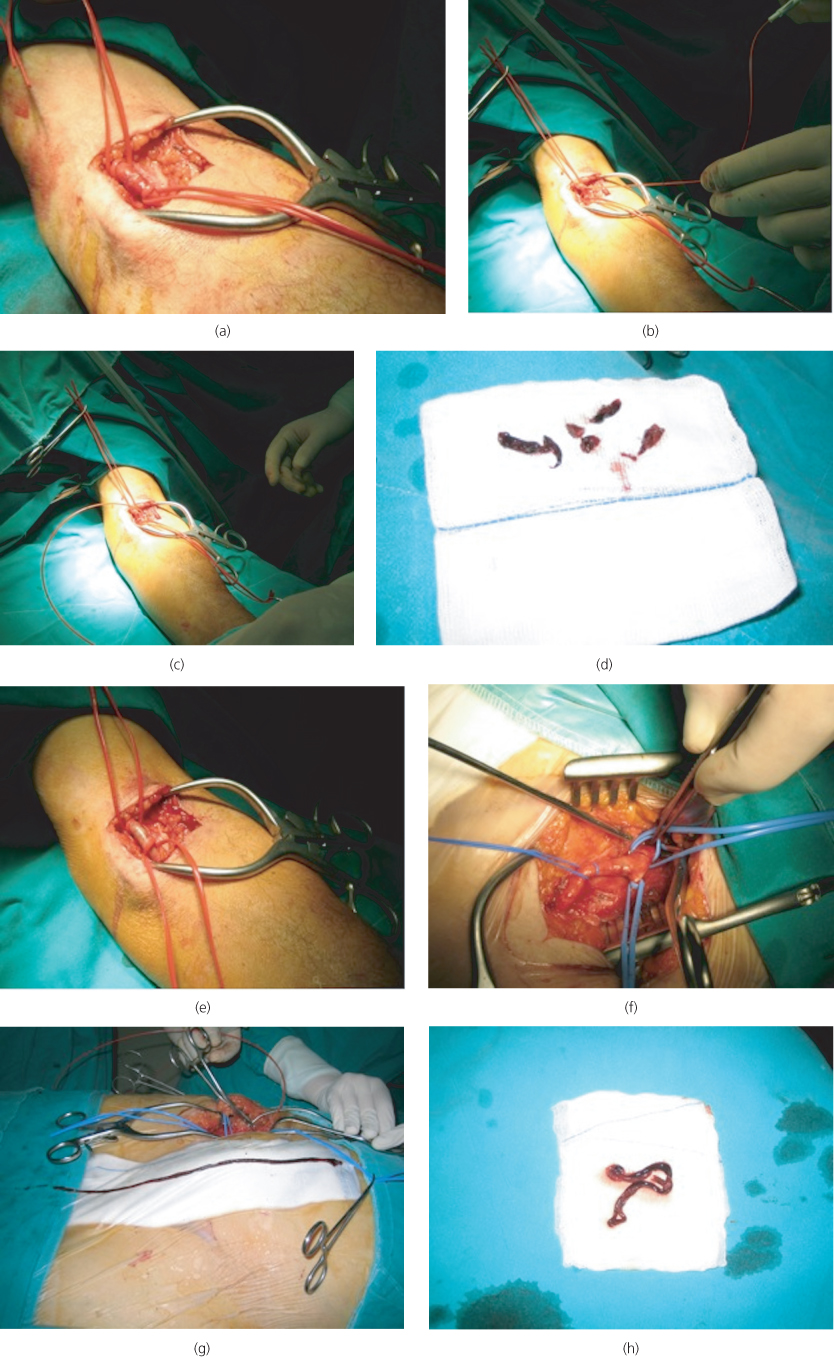

When an embolus is suspected, embolectomy with a balloon catheter is performed under local anaesthesia (Figure 6.5). Standard embolectomy is usually performed blind (i.e. there is no control over the direction of the catheter past the popliteal trifurcation), and as a result, residual thrombus may well be left behind. An alternative is to use an over-the-wire catheter that can be selectively guided to each one of the crural arteries under fluoroscopy. On completion of the procedure, an on-table angiogram can be performed to check the result. If the initial procedure is unsatisfactory, further options are exposure and direct embolectomy of the popliteal and distal arteries, bypass or on-table thrombolysis.

Figure 6.5 Balloon catheter embolectomy. In the upper limb, an antecubital fossa incision is made to expose the brachial artery (a), a transverse arteriotomy is performed, the balloon catheter (known as Fogarty catheter) is passed both proximally (b) and distally (c) until two successive passes yield no further clots (d) and the arteriotomy is repaired (e). In the lower limb, a vertical groin incision is made to expose the femoral bifurcation and the arteries are controlled with silastic slings (f). Here, the entire column of the propagated thrombus has been removed intact from the superficial femoral artery (g, h).

Contrary to embolism, arterial thrombosis is unlikely to be effectively treated by balloon catheter thrombectomy alone. Provided that ischaemia is not absolute (which is usually the case in most patients with thrombosis due to pre-existing disease), there is time for preoperative angiography. A wider variety of options are available in these patients, including open surgery (endarterectomy, bypass), endovascular interventions (balloon angioplasty, stenting) or thrombolysis.

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis for ALI is best achieved via a percutaneous, catheter-directed, intra-arterial technique. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) and urokinase are currently the most commonly used thrombolytic agents, whereas streptokinase is less popular because of fear of allergic reactions. Compared to surgery, thrombolysis is generally less invasive and can open both large and small vessels (the latter being inaccessible to surgical thrombectomy or bypass). It may be used as a monotherapy, i.e. obviating the need for surgery, or it may convert a major emergency operation to an elective one of a lesser magnitude. By dissolving the thrombus, thrombolysis will often unmask the underlying, flow-limiting lesion that triggered thrombosis and permit subsequent correction by the most appropriate percutaneous or open surgical technique. However, it cannot be used in patients with complete ischaemia because thrombus dissolution takes several hours and permanent muscle death follows 6–12 h of ischaemia. Such patients should undergo emergency revascularisation. Even so, thrombolysis may still be used in these cases as an adjunct to clear run-off vessels. There are several contraindications to thrombolysis, so one should be careful in patient selection (Table 6.6). Because of the risk of bleeding and systemic complications (minor haemorrhage 20–40%, major haemorrhage 5–10%, stroke 3%), and also because the ischaemic leg may deteriorate, careful monitoring during thrombolysis is necessary. This is best done in an intensive care or step-down unit by experienced nursing and medical staff. Clinical deterioration during thrombolysis signals the need to interrupt the infusion and proceed with surgical revascularisation. New developments, on the other hand, such as mechanical or aspiration thrombectomy, may enhance the effectiveness of thrombolysis, particularly, in cases of high bulk of initial thrombus or where the initial thrombolysis fails (high amount of residual thrombus).

Table 6.6 Contraindications for thrombolysis in ALI.

| Active internal bleeding (absolute) |

| Intolerable ischaemia |

| Cerebrovascular accident within 2 months |

| Intracranial pathology (known intracerebral tumour, aneurysm or arteriovenous malformations) |

| Craniotomy within 2 months |

| Transient ischaemic attack within 2 weeks |

| Recent major surgery or trauma (<10 days) |

| Vascular surgery within 2 weeks |

| Previous gastrointestinal tract bleeding |

| Severe hypertension |

| Coagulation disorders |

| Pregnancy |

| Recent eye surgery or diabetic retinopathy |

| Puncture of a non-compressible vessel or biopsy within 10 days |

| Severe liver disease |

| Severe renal failure |

Several randomised trials and a recent Cochrane review concluded that there is no difference in limb salvage or death at 1 year, and, therefore, universal initial treatment with either surgery or thrombolysis cannot be advocated on the available evidence. Thrombolysis may be associated with a higher risk of ongoing limb ischaemia and haemorrhagic complications, but this higher risk of complications must be balanced against the risks of surgery in each person. The final choice would depend on local policy, preference and expertise.

Ischaemia–reperfusion

Patients treated for severe ALI are at risk of developing ischaemia–reperfusion syndrome, a condition that can be more harmful than ischaemia alone. When perfusion of ischaemic muscles is restored, metabolites from damaged and disintegrated muscle cells are spread systemically and may cause further tissue injury both locally (manifested as compartment syndrome) and at remote sites. Oxygen free radicals and neutrophil activation play an important role in this complex process. Systemic manifestations may include acute renal failure (metabolic acidosis, hyperkalaemia, myoglobinuria, and acute tubular necrosis), myocardial depression (cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, infarction and cardiac arrest), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), hepatic failure or gastrointestinal endothelial oedema leading to increased gastrointestinal vascular permeability and endotoxic shock. The elevated mortality encountered in severe ALI may be due to the above-mentioned complications and avoiding or minimising the effects of reperfusion may improve survival. Candidates at significant risk for reperfusion are those with longer ischaemia times (>4–6 h) and those with more proximal occlusions (e.g. saddle emboli in the aortic bifurcation) where the affected muscle mass is large. Treatment includes correction of underlying abnormalities, such as acidosis and hyperkalaemia, hydration and maintaining a good urine output, alkalinisation of the urine with sodium bicarbonate, mannitol (acting both as an osmotic agent to induce diuresis and a scavenger of deleterious oxygen free radicals) and, in some cases, haemodialysis. Cardiorespiratory support may also be required in certain patients.

Compartment syndrome

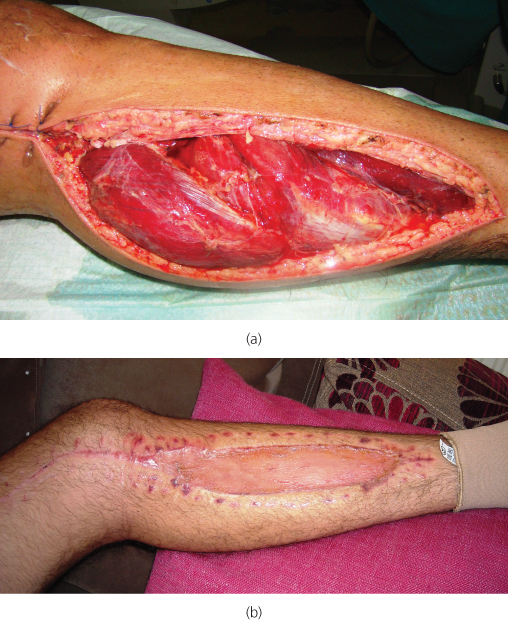

The acute inflammation in the muscle after restoring perfusion leads to swelling and, as the available space for the muscles within the confined fascial compartment is limited, the increased pressure in the compartments reduces capillary blood perfusion below the level necessary for tissue viability (compartment syndrome). As a result, nerve injury and muscle necrosis can occur. The amount of oedema parallels the severity and duration of the ischaemia. The main clinical feature is pain—often very strong and ‘out of proportion’—which is accentuated by squeezing the calf or passive dorsiflexion of the foot. Pedal pulses may still be present and do not exclude the syndrome. Treatment consists of emergency fasciotomy (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6 Fasciotomy for compartment syndrome. Decompression of all four compartments of the leg has been achieved using two long incisions, one placed laterally (not seen here) and one medially in the calf (a). The wounds can be closed or skin-grafted later (b).

Post-operative anticoagulation

Following embolectomy, patients with atrial fibrillation should be on long-term anticoagulation with warfarin to reduce the risk of recurrent embolism. When non-cardiac causes of embolism (such an aneurysm or a penetrating aortic ulcer) are identified, these should be treated accordingly. If the source of the emboli is not clear, it should be investigated. If no source of embolism is found (which is the case in 5–12% of patients despite a full diagnostic work-up), anticoagulation should continue long term. Long-term anticoagulation should also be considered in cases of arterial thrombosis when the risk of recurrent thrombosis persists.

Prognosis

The outlook for patients admitted with ALI has generally been poor. Only 60–70% of patients leave the hospital with an intact limb. The 30-day mortality is 15–30% and 15% of the survivors undergo an amputation. Mortality is higher in patients presenting with embolic causes (due to the underlying cardiac disease), whereas limb loss is higher in those with thrombosis. Long-term outcome is equally poor with only 30–40% of the patients being alive at 5 years (probably due to a combination of advanced age and co-morbidities).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree