Chapter 22

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

1. What is acute decompensated heart failure? Isn’t it just a worsening of chronic heart failure?

2. Are there clinically important subcategories of ADHF?

Hypertensive acute heart failure: Data from large registries such as ADHERE and OPTIMIZE have shown that a substantial portion of ADHF patients are hypertensive on initial presentation to the emergency department. Such patients often have relatively little volume overload, preserved or only mildly reduced ventricular function, and are more likely to be older and female. Symptoms often develop quickly (minutes to hours), and many such patients have little or no history of chronic heart failure. Hypertensive urgency with acute pulmonary edema represents an extreme form of this phenotype.

Hypertensive acute heart failure: Data from large registries such as ADHERE and OPTIMIZE have shown that a substantial portion of ADHF patients are hypertensive on initial presentation to the emergency department. Such patients often have relatively little volume overload, preserved or only mildly reduced ventricular function, and are more likely to be older and female. Symptoms often develop quickly (minutes to hours), and many such patients have little or no history of chronic heart failure. Hypertensive urgency with acute pulmonary edema represents an extreme form of this phenotype.

Decompensated heart failure: This describes patients with a background of significant chronic heart failure, who develop symptoms of volume overload and congestion over a period of days to weeks. These patients typically have significant left ventricular dysfunction and chronic heart failure at baseline. Although specific triggers are poorly understood, episodes are often triggered by noncompliance with diet or medical therapy.

Decompensated heart failure: This describes patients with a background of significant chronic heart failure, who develop symptoms of volume overload and congestion over a period of days to weeks. These patients typically have significant left ventricular dysfunction and chronic heart failure at baseline. Although specific triggers are poorly understood, episodes are often triggered by noncompliance with diet or medical therapy.

Cardiogenic shock/advanced heart failure: Although patients with advanced forms of heart failure are often seen in tertiary care centers, they are relatively uncommon in the broader population (probably fewer than 10% of ADHF hospitalizations). These patients may present with so called low-output symptoms (e.g., confusion, fatigue, abdominal pain, or anorexia) that may make diagnosis challenging. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] less than 90 mm Hg) and significant end-organ dysfunction (especially renal dysfunction) are common features. Many of these patients have concomitant evidence of significant right ventricular dysfunction, with ascites or generalized anasarca.

Cardiogenic shock/advanced heart failure: Although patients with advanced forms of heart failure are often seen in tertiary care centers, they are relatively uncommon in the broader population (probably fewer than 10% of ADHF hospitalizations). These patients may present with so called low-output symptoms (e.g., confusion, fatigue, abdominal pain, or anorexia) that may make diagnosis challenging. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] less than 90 mm Hg) and significant end-organ dysfunction (especially renal dysfunction) are common features. Many of these patients have concomitant evidence of significant right ventricular dysfunction, with ascites or generalized anasarca.

3. What is the role of biomarkers like B-type natriuretic peptides (BNPs) in the diagnosis of ADHF?

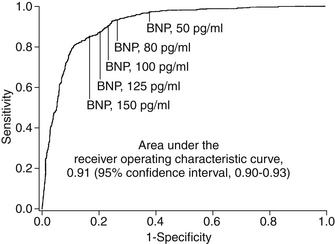

Although the clinical symptoms (dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea [PND], orthopnea, fatigue) and signs (elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary rales, edema) of ADHF are well known, the diagnosis can often be challenging in patients presenting to acute care settings. This is especially true in the elderly and patients with significant comorbid conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The development of natriuretic peptides as a diagnostic tool has been a major advance in ADHF diagnosis. The clinically available natriuretic peptides for ADHF diagnosis include BNP and its biologically inert amino-terminal fragment, N-terminal prohormone of B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Despite some subtle differences between these two biomarkers, they provide similar diagnostic information when used in patients presenting to the emergency department with unexplained dyspnea, although the range of values is significantly different (in general, NT-proBNP levels are approximately 5 to 10 times greater than BNP levels in the same patient). The landmark Breathing Not Properly Study measured BNP levels in 1586 patients presenting to the emergency department with unexplained dyspnea. In this study, treating physicians were blinded to BNP values and a panel of cardiologists adjudicated whether hospitalizations were due to ADHF or other causes (based on all clinical data other than the BNP values). As shown in Figure 22-1, a cutoff of 100 pg/mL of BNP had a positive predictive value of 79% and a negative predictive value of 89% for the diagnosis of ADHF. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.91, suggesting a very high degree of accuracy for establishing the diagnosis of ADHF. Subsequent studies have demonstrated similar findings for NT-proBNP, although optimal diagnostic cutoffs are different (450 pg/mL for patients younger than 50 years and 900 pg/mL for patients older than 50 years). The use of natriuretic peptide has now become the standard of care in the diagnosis of patients with dyspnea presenting to acute care settings, and has a class I indication (“should be done”) in clinical practice guidelines.

Figure 22-1 Receiver operating characteristic curve for use of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) in making diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure in patients with acute unexplained dyspnea. (Adapted from Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM, et al: Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med 347:161-167, 2002.)

4. What features suggest patients who are particularly high risk?

Analysis of large datasets from both clinical trials and registries of ADHF patients have identified a few features that consistently suggest a high risk of short-term morbidity and mortality in patients hospitalized with ADHF (Box 22-1). Across studies, the most consistent of these are blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine, SBP, and hyponatremia. Interestingly, BUN has consistently proved to be a stronger predictor of outcomes than creatinine (Fig. 22-2). One potential explanation of this finding is that BUN may integrate both renal function and hemodynamic information. Unlike the situation in many other cardiovascular conditions, higher blood pressure has consistently been associated with lower

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree