Chapter 18 Acute Coronary Syndromes

The term acute coronary syndrome covers a broad spectrum of clinical situations, from unstable angina to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). These are, with rare exceptions (Table 18-1), a consequence of acute thrombus formation related to a disrupted coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Over the past decade, tremendous progress has been made in our understanding of the pathophysiology, classification, patient risk stratification, and management of acute coronary syndromes. However, they remain an important cause of morbidity and mortality; they were the most common cause of adult hospital admissions in the United States in 2001.

Table 18-1 Causes of Regional Myocardial Ischemia Other Than Atherosclerotic Disease

| Spontaneous coronary artery dissection |

| Coronary emboli (thrombus, vegetations, atrial myxoma, valve leaflet calcification) |

| Coronary artery spasm |

| Coronary arteritis |

| Aortic dissection involving the aortic root |

| Transplant vasculopathy |

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The coronary atherosclerotic plaque is the hallmark lesion of coronary artery disease. It is located in the intima of the artery and consists of a central lipid core surrounded by a fibrous capsule which separates the core from the vessel lumen (Fig. 18-1A). Atherosclerotic plaques most likely originate from preexisting intimal lesions (intimal masses or thickenings and intimal xanthoma or fatty streaks) that are present from childhood. The majority of these intimal lesions regress or remain stable. However, in the presence of atherogenic risk factors (smoking, hypertension, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia)—which result in endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation—these intimal lesions can lead to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. Endothelial cell dysfunction and inflammation are key features of this process.1,2

Thrombus Formation on Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaques

The underlying pathophysiologic process of acute coronary syndromes involves thrombus formation on an atherosclerotic plaque (Fig. 18-1B).3 Three separate mechanisms appear to result in thrombus formation: (1) plaque rupture; (2) plaque erosion; (3) thrombosis associated with a calcified nodule (Table 18-2).

Table 18-2 Plaque Thrombosis: Mechanisms and Plaque Characteristics

Rights were not granted to include this table in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book.

(Figures from Naghavi M, Libby P, Falk E, et al: From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient: A call for new definitions and risk assessment strategies: Part I. Circulation 108:1664, 2003.)

Following plaque disruption the subendothelial connective tissue, the tissue-factor-rich lipid core, or both are exposed to blood. This results in platelet activation and aggregation and in stimulation of the coagulation cascade, eventually leading to thrombus formation. Thrombus may be limited and remain within the plaque, in which case it is clinically silent. Alternatively, thrombus formation may progress and become exposed to blood flow within the artery lumen (mural thrombus). Platelet-thrombin emboli may pass distally and cause microvascular obstruction and result clinically in a non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Further growth of the thrombus eventually leads to intraluminal obstruction with resultant macrovascular ischemia. When thrombus causes total vessel occlusion, an ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome results.

The morphologies of plaques that are at high risk for thrombus formation through these mechanisms are quite distinct.4 Furthermore, the majority of these lesions are non-flow-limiting stenoses of less than 70% diameter. Therefore, the risk for future acute coronary ischemic events appears to be dependent largely on the presence of these morphologically distinct plaques, rather than on the presence of severely stenotic lesions. The term vulnerable plaque is used to describe lesions that are prone to thrombus formation.

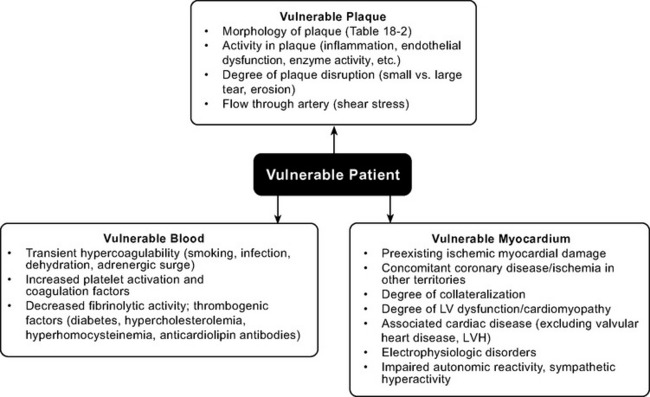

Vulnerable Patient

Whether disruption of a vulnerable plaque in an individual patient results in a clinical event is dependent not only on local plaque-related factors but also on the thrombogenicity of the patient’s blood and the state of the myocardium at the time of the event. The concept of the vulnerable plaque has been extended to include vulnerable blood, vulnerable myocardium, and the vulnerable patient (Fig. 18-2).5–7 Assessment and treatment strategies should address the vulnerable patient.

CLASSIFICATION OF ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

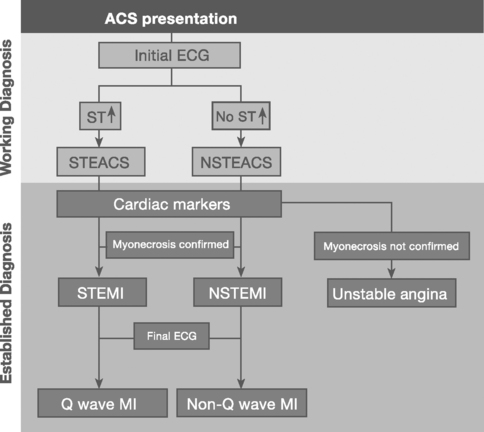

Establishing a Working Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome

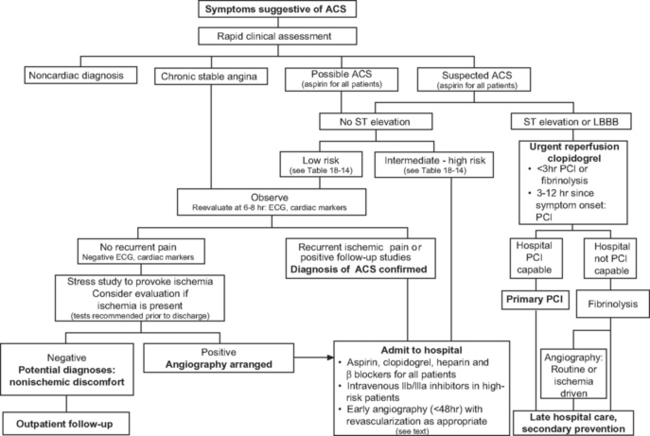

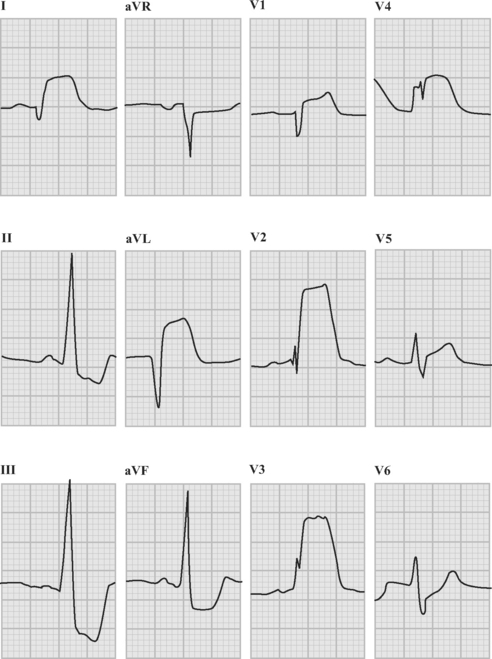

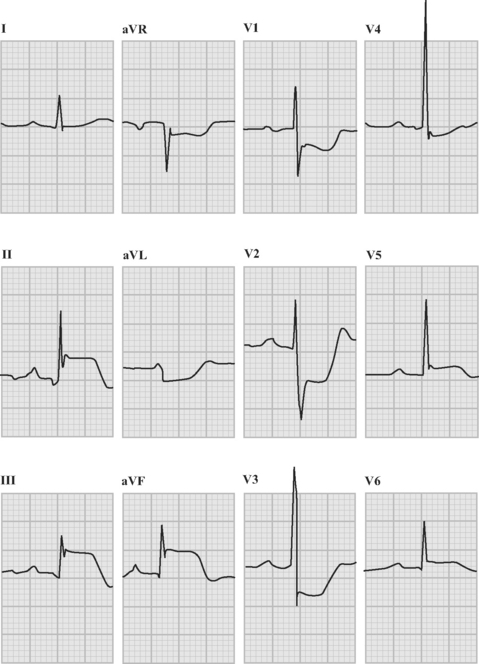

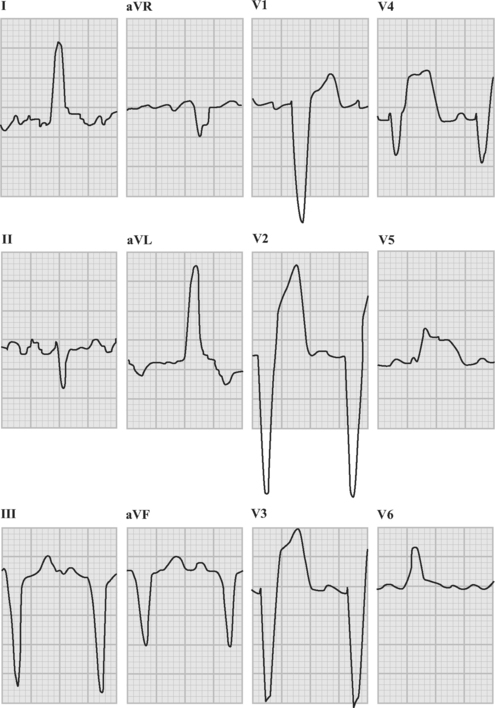

Patients with acute coronary syndromes are classified into two groups on the basis of ST-segment changes on their admission electrocardiograms (ECGs) (Fig. 18-3). This classification provides an initial working diagnosis so that appropriate therapy can be initiated.

ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

Sustained ST-segment elevation on an ECG, in the context of an acute coronary syndrome, is usually indicative of an occluded coronary artery. Included within this subset are those patients presenting with a presumed new left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern on the initial ECG. These patients require urgent pharmacologic or catheter-based reperfusion.8

Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome

In the absence of sustained ST elevation, patients with acute coronary syndromes represent a heterogeneous population, spanning transient ST-segment elevation, ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion, and the absence of ECG changes. This group of patients does not require urgent reperfusion therapies and, in fact, pharmacologic reperfusion is harmful. The ECG provides important prognostic information upon which antithrombotic treatment and early revascularization can be initiated—either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).9

Establishing a Final Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction is defined as myocyte necrosis in the setting of an acute coronary syndrome, PCI, or CABG (Table 18-3). The diagnosis of myocardial infarction in a patient with an acute coronary syndrome is based on: (1) biochemical markers; (2) evolving ECG changes; (3) clinical features.

Table 18-3 Definition of Myocardial Infarction

The European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology: Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Eur Heart J 21:1502-1513, 2000.

CK-MB, MB fraction of creatine kinase; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

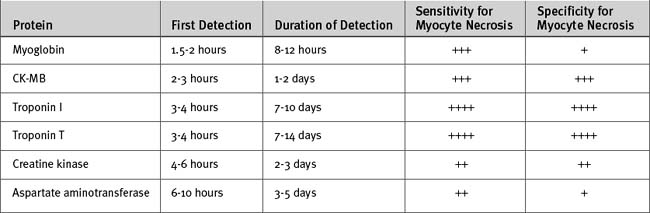

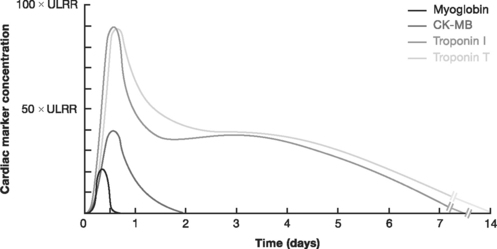

Biochemical evidence of myocardial infarction involves a typical pattern of elevation followed by a gradual fall of the troponins (either I or T) or of the creatine kinase MB fraction (CK-MB) (see Table 18-6 and Fig. 18-11 in Laboratory Tests, later in the text). When using troponin T, a level above 0.03 μg/l is considered elevated; the cut-off for troponin I depends on the assay used. CK-MB increases more rapidly than the troponins and provides early evidence of myocardial infarction, but CK-MB is a less sensitive and less specific marker of myocyte damage.

Figure 18.11 Kinetic profiles of cardiac markers following ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

(From French JK, White HD: Clinical implications of the new definition of myocardial infarction. Heart 90:99-106, 2004.) ULRR, upper limit of the reference range.

ASSESSMENT AND DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

A targeted history, a clinical examination, and investigations are needed to confirm a diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome, to exclude other causes of the presenting symptoms (Table 18-4), to risk-stratify the patient, and to initiate appropriate therapy without delay. The assessment and risk stratification of a patient should be a dynamic process throughout his or her hospitalization (Fig. 18-4).

Table 18-4 Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms Associated With Acute Coronary Syndromes

| Aortic dissection |

| Pulmonary embolus |

| Peptic ulcer |

| Tension pneumothorax |

| Esophageal rupture with mediastinitis |

| Pericarditis |

| Gastroesophageal reflux and spasm |

| Musculoskeletal/chest wall pain |

| Pneumonia/pleurisy |

| Biliary or pancreatic pain |

| Cervical disk or neuropathic pain |

History

Chest pain or discomfort is the principal symptom of myocardial ischemia in the majority of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Most often the discomfort is central or retrosternal and is described as crushing, squeezing, heavy, or tight and may radiate into the back between the shoulder blades, neck, jaw, left shoulder, or arm. Accompanying symptoms may include shortness of breath, weakness, sweating, nausea, and vomiting. Some patients, notably diabetic patients and the elderly, may have no discomfort but present with breathlessness, syncope, palpitations, or nonspecific symptoms of general lack of wellness.

Clinical Examination

Physical signs of left ventricular failure may be present, such as S3 and S4 heart sounds, crackles and wheezes on chest auscultation, and evidence of systemic hypoperfusion. A mid or late systolic murmur may indicate the presence of mitral regurgitation. Cardiogenic shock occurs in about 4% of patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (see Chapter 19).

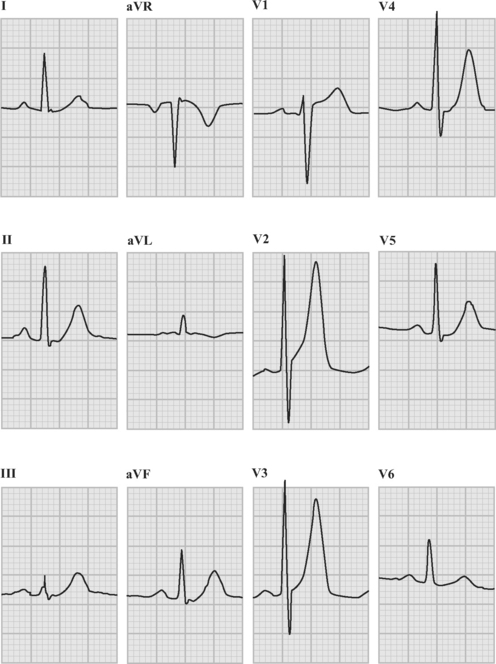

Electrocardiogram

An ECG should be obtained and reviewed immediately on presentation. If the initial ECG is normal or only mildly abnormal (Fig. 18-5) and there is a high clinical suspicion of myocardial infarction, serial ECGs should be performed at 5- to 10-minute intervals or, ideally, continuous ST-segment monitoring should be instituted. ECGs should be obtained every 6 to 8 hours in all other patients until an established diagnosis has been made.

ECG in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes

The following criteria are used to define ST-segment elevation: