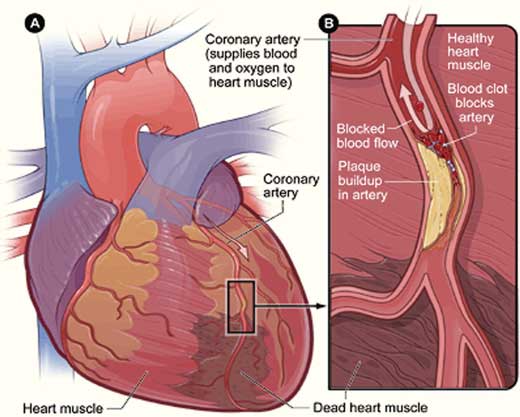

Figure 9.1 – Schematic diagram of ACS.

Acute coronary syndrome In A Heartbeat

Definition | Syndrome consisting of unstable angina, NSTEMI and STEMI |

Epidemiology | Most common cause of death in Western countries |

Aetiology | Most commonly caused by atherosclerosis |

Clinical features | Symptoms: central crushing retrosternal chest pain, diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting |

Investigations | 1st-line: blood tests, cardiac troponin, ECG, CXR |

Management | Immediate: dual antiplatelet therapy, oxygen, morphine, GTN, beta-blockers |

9.2 Epidemiology

- ACS causes approximately 150 000 admissions a year in the UK

- ACS accounts for an estimated 30% of all deaths worldwide

- Male predominance; may be underdiagnosed in women

- More commonly seen in older age groups

- One of the most common causes of death worldwide

- Approximately 8% of patients admitted for a heart attack will be readmitted within a month.

// PRO-TIP //

The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) study indicated that 38% of ACS patients present with a STEMI.

9.3 Risk factors

Non-modifiable risk factors:

- Age: average age 66 for males, 70 for females at present

- Male sex – being male increases the risk of developing acute coronary syndrome when compared to pre-menopausal women, but this risk equalises when compared to post-menopausal women

- Ethnicity: South Asians are at higher risk

- Family history of coronary heart disease: <55 years old in men, <65 years old in women

- Previous myocardial infarction.

// Why? //

Oestrogen is a protective factor in pre-menopausal women. In post-menopausal women, despite its therapeutic advantages, using hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is associated with significant risks (endometrial cancer, thromboembolism). The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study showed that women with endogenous oestrogen deficiency are seven times more likely to develop coronary artery disease. It is important to note that it is not recommended in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Modifiable risk factors:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Cigarette smoking

- Dyslipidaemia (low HDL, high LDL)

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle and physical inactivity

9.4 Pathophysiology

Most cases of acute coronary syndrome result from sudden changes in a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque of the coronary arteries. In stable angina, the plaque is characterised by a thick fibrous cap and a small lipid core. ACS, on the other hand, is characterised by an unstable plaque with a thin fibrous cap and large lipid content. The plaque is prone to rupture and fissure, and when this occurs, exposure to the plaque elements triggers the coagulation cascade and promotes the formation of an acute coronary thrombus.

Figure 9.2 – Formation of a coronary thrombus.

9.4.1 ST elevation myocardial infarction

If there is complete occlusion of the coronary vessel by the resultant thrombus, infarction and necrosis develop rapidly, characterised by ST elevation on ECG (STEMI).

9.4.2 | Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction |

If the thrombus does not fully occlude the coronary vessel, blood supply to the myocardium is not fully compromised and varying levels of ischaemia may occur. This depends on the degree of obstruction, extent of collateralisation and the presence of emboli. This typically manifests with ST changes, including ST depression and/or T-wave inversion. In unstable angina there is no myocardial necrosis and troponin is not raised. In non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) there is a rise in troponin, indicating that underlying injury has taken place.

9.5 Clinical features

9.5.1 Key features

EXAM | Chest pain in ACS is classically associated with the sudden onset of a severe, left-sided or central crushing retrosternal chest pain. The pain may radiate to the jaw, neck or arm (usually the left).

Only 20% of ACS patients have a history of long-standing angina. |

- Chest pain

- Other important features include a sense of impending doom (angor animi ), breathlessness, sweating, nausea and vomiting

- Atypical presentations may also occur

// PRO-TIP //

Atypical presentations occur in at least 20% of patients, particularly in those with autonomic dysfunction (diabetics and the elderly). Possible presentations include:

- Silent MI – no chest pain

- Epigastric pain

- Pulmonary oedema, syncope and oliguria

- Hypotension and acute confusional state

9.5.2 Examination findings

- Levine’s sign: a clenched fist on the chest (specificity between 76 and 86%)

- Pallor, diaphoresis and anxiety

- Low-grade pyrexia

- Occasionally, a fourth heart sound may be heard

9.6 Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes a variety of conditions, arranged below in order, from least serious to life-threatening:

- Musculoskeletal chest pain

- Costochondritis

- Pericarditis

- Myocarditis

- Prinzmetal’s angina (refer to Chapter 8)

- Pulmonary: pneumothorax, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism

- Gastrointestinal: oesophagitis, diffuse oesophageal spasm (nutcracker oesophagus), oesophageal rupture

- Aortic dissection

GUIDELINES: Diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (NICE, 2010)

NICE advises against the evaluation of patient response to glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) as a factor in favour of the diagnosis of ACS.

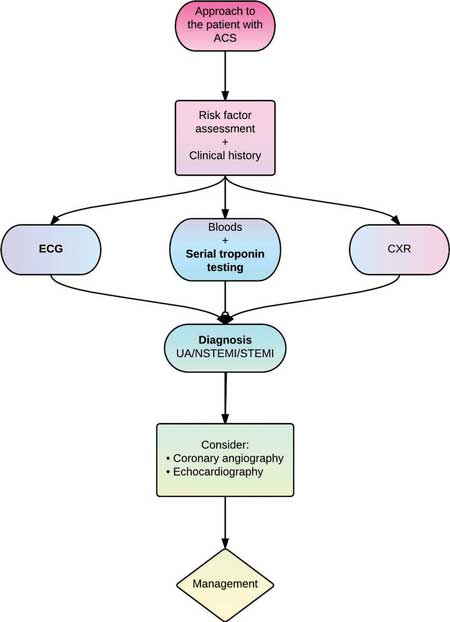

9.7 Investigations

The aim is to establish the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, confirm the diagnosis by eliciting evidence of myocardial damage, and to exclude other conditions that may mimic ACS.

- Blood tests: FBC, U&Es, glucose, lipid profile, LFTs and serial cardiac troponins

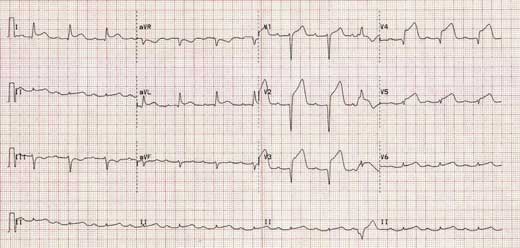

- Electrocardiogram: this is a key investigation. A series of changes observed can be correlated with the age of the infarct (see below). ST elevation will eventually resolve, giving rise to deep T wave inversion and the emergence of Q waves.

- ST elevation: hours

- T wave inversion: days

- pathological Q waves: days to months. It is present in transmural infarcts

- the ECG findings vary according to the type of ACS

- features of UA/NSTEMI:

– ST depression

– T-wave inversion (TWI is normal in aVR, III and V2)

– may be normal.

- ST elevation: hours

Figure 9.3 – Approach to the patient with ACS. UA: unstable angina.

EXAM | Features of STEMI:

|

Figure 9.4 – ST elevation in leads V2–V5 consistent with an anteroseptal MI.

- Cardiac troponin: cardiac troponin I and T are highly sensitive and specific for acute myocardial infarction. Troponin is recommended in the diagnosis, detection of

re-infarction and the evaluation of prognosis in all patients with ACS.

- elevated as early as 2 hours, peaks at 12–18 hours, and remains elevated for approximately 14 days (refer to Chapter 3)

- should be requested on presentation and 12 hours after onset of symptoms

- the universal definition of myocardial infarction states that the 99th centile upper reference limit Is used to define myocardial necrosis (see below)

- raised in other conditions and should not be used in isolation (see below)

- the higher the troponin level, the greater the 30-day and 6-month mortality.

- elevated as early as 2 hours, peaks at 12–18 hours, and remains elevated for approximately 14 days (refer to Chapter 3)

- Chest radiography: to exclude other causes of chest pain and dyspnoea such as aortic dissection, and to look for complications of ACS such as acute pulmonary oedema.

// PRO-TIP //

With the advent of high-sensitivity troponin assays, very low levels of troponin can be detected. While these newer assays improve diagnostic sensitivity, they are likely to affect clinical specificity. This is primarily because troponin can be elevated in several other conditions: acute heart failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, renal failure and sepsis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree