Infectious causes (>2/3 of cases)

Viral (especially enteroviruses, adenoviruses, EBV, CMV, parvovirus, HCV, HIV)

Bacterial (especially tuberculosis)

Other (rare): fungal (rare; histoplasma more likely in immunocompetent patients; aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candida more likely in immunosuppressed host). Parasitic (very rare; echinococcus, toxoplasma)

Non-infectious causes (about 1/3 of cases)

Systemic inflammatory diseases (especially: systemic lupus erythematosus, Rheumathoid arthritis, scleroderma, Sjogren syndrome, Behcet syndrome)

Autoinflammatory diseases (especially familial mediterranean fever, TRAPS)

Post-cardiac injury syndromes (post-pericardiotomy syndrome, post-myocardial infarction, post-traumatic following any kind of interventional cardiovascular procedure, irradiation or accidental trauma)

Neoplastic diseases (especially secondary to lung and breast cancer or lymphomas, rarely as primary tumours of the pericardium, especially pericardial mesothelioma)

Drugs or toxic agents (rare): procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, and phenytoin (lupus-like syndrome), penicillins (hypersensitivity pericarditis with eosinophilia), doxorubicin, and daunorubicin (often associated with a cardiomyopathy; may cause a pericardiopathy)

Current diagnostic criteria do not allow the identification of the cause in more than two thirds of patients in Western Europe and North America. In developed countries such cases are supposed to be viral or post-viral and named as “idiopathic”.

Diagnosis and Workup

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is based on clinical criteria. Patients with an infectious etiology may present with signs and symptoms of systemic infection such as fever and leukocytosis. Viral etiologies in particular may be preceded by “flu-like” respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients with a known autoimmune disorder or malignancy may present with signs or symptoms specific to their underlying disorder.

The major clinical manifestations of acute pericarditis include:

Chest pain in >90 % of cases – typically sharp and pleuritic, improved by sitting up and leaning forward

Pericardial friction rub in 25–33 % of cases – a superficial scratchy or squeaking sound best heard with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the left sternal border

Electrocardiogram (ECG) changes – new widespread ST elevation or PR depression in 50–60 % of cases

Pericardial effusion in >60 % of cases

The diagnosis of acute pericarditis is reached with at least two of four of these clinical manifestations [1, 5].

Criteria for the diagnosis of recurrent pericarditis [4] include a documented first attack of acute pericarditis, according to previously stated diagnostic criteria; a symptom-free interval of 6 weeks or longer; and evidence of subsequent recurrence of pericarditis. Patients with persistent pericarditis or those with a symptom-free interval of less than 6 weeks should be given the diagnosis of incessant pericarditis [5, 6].

Recurrence is documented by recurrent pain and one or more of the following signs:

a pericardial friction rub,

changes on electrocardiography (ECG),

echocardiographic evidence of pericardial effusion, and

an elevation in the white-cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein level

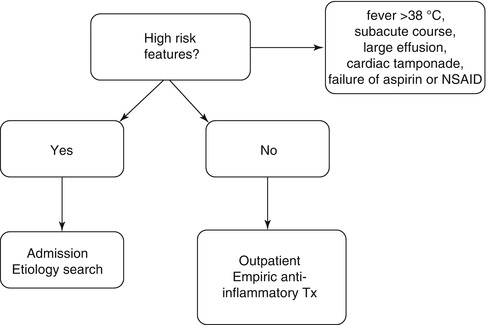

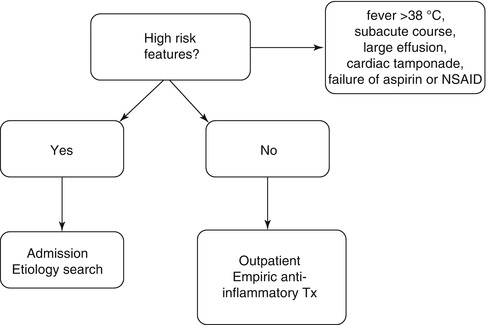

Specific features at presentation suggest an increased risk of a non-idiopathic, non-viral etiology and possible complications during follow-up [11]. These features include: fever >38 °C, subacute course, large effusion or cardiac tamponade, and failure of aspirin or of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Patients without high risk features may be managed as outpatient (Fig. 8.1) [12–14].

Fig. 8.1

Triage of pericarditis (see text for explanation)

Initial evaluation of an patient with a acute or recurrent pericarditis include first, the initial history and physical examination – This evaluation should consider disorders that are known to involve the pericardium, such as prior malignancy, autoimmune disorders, uremia, recent myocardial infarction, and prior cardiac surgery. The examiner should pay particular attention to auscultation for a pericardial friction rub and the signs associated with tamponade.

Subsequent testing [12, 13] should include:

Complete blood count, troponin level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or serum C-reactive protein level, an electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and chest x-ray in all cases.

Blood cultures if fever higher than 38 ºC (100.4 ºF) or signs of sepsis.

Tuberculin skin test or an interferon-gamma release assay (e.g, QuantiFERON TB assay) if not recently performed. The interferon-gamma release assay is most helpful in immunocompromised or HIV positive patients and in regions where tuberculosis is endemic.

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer in selected cases (eg, young women, especially those in whom the history suggests a rheumatologic disorder). Rarely, acute pericarditis is the initial presentation of a systemic inflammatory disease (SID), i.e. systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It is important to recognize that a positive ANA is a non-specific test. A rheumatology consult should be sought in patients with pericarditis in whom a diagnosis of a SID is suspected.

HIV serology

Computed tomography (CT) may be useful to confirm the diagnosis and especially evaluate concomitant pleuropulmonary diseases and lymphadenopathies, thus suggesting a possible etiology of pericarditis (i.e. TB, lung cancer). Non-calcified pericardial thickening with pericardial effusion is suggestive of acute pericarditis. Moreover, with the administration of iodinated contrast media, enhancement of the thickened visceral and parietal surfaces of the pericardial sac confirms the presence of active inflammation. Computed tomographic attenuation values can help in the differentiation of exudative fluid (20–60 Hounsfield units), as found with purulent pericarditis, and simple transudative fluid (<10 Hounsfield units).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may be performed if the echocardiogram is unrevealing but the diagnosis of acute pericarditis is suspected, especially in patients with ongoing fever, poor response to treatment, or suspicion of hemodynamic compromise [15].

Echocardiography should be performed in all cases, with urgent echocardiography if cardiac tamponade is suspected. Even a small effusion can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis of pericarditis, although the absence of an effusion does not exclude the diagnosis. In addition, echocardiography can be particularly helpful if purulent pericarditis is suspected, if there is concern about myocarditis, or if there is radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly, particularly if this is a new finding.

The 2003 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Society of Echocardiography (ACC/AHA/ASE) guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography stated that evidence and/or general agreement supported the use of echocardiography for the evaluation of all patients with suspected pericardial disease [16]. Similarly, a 2013 expert consensus statement from the ASE recommends echocardiography for all patients with acute pericarditis [15].

Multimodality imaging is an integral part of modern management for pericarditis and pericardial diseases. Among multimodality imaging tests, echocardiography is most often the first-line test, followed by CMR and/or CT [15].

Viral studies are not cost-effective, since the yield is low and management is not altered [17].

Pericardiocentesis should be performed for therapeutic purposes in patients with cardiac tamponade and diagnostic purposes when a bacterial or neoplastic etiology is suspected and not assessed by other diagnostic means. In fact, the definite diagnosis of such etiologies relies on the demonstration of the etiological agent in the pericardial fluid or tissue [13]. Persistent symptomatic disease >3 weeks may warrant a pericardial biopsy.

Management

Medical treatment of pericarditis should be targeted at the cause as much as possible. For bacterial causes, specific antibiotic therapies are the key for successful management. The same applies for neoplastic pericarditis where oncologic therapies provide causative treatment [18, 19]. Nevertheless if the cause is unknown or viral there are no specific therapies available and we may provide successful treatments for patients as we do for other medical conditions when the cause cannot be known (i.e. primary hypertension). The mainstay of the medical therapy of acute and recurrent pericarditis is aspirin or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (generally ibuprofen or indomethacin) (Class I indication, LOE A) [20]. The choice of the specific drug should be based on previous history in order to select a drug that has been efficacious in previous attacks of pericarditis, concomitant diseases (i.e. favoring aspirin on patients who already are or need an antiplatelet agent), and last, but not least, physician experience [21]. An attack dose is recommened for 7–10 days till symptoms resolution and C-reactive protein normalization [18–23]. Colchicine may help to hasten symptoms resolution, improve remission rates at 1 week, and reduce recurrence by 50 % at 18 months (Class I indication, LOE A) [4, 5].

Corticosteroids should be used as second choice for patients refractory to more than 1 NSAID plus colchicine, contraindications or intolerance to aspirin or NSAID, specific indications (i.e. SID, pregnancy). Low to moderate doses (i.e. prednisone 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day) should be favored instead of high doses (i.e. prednisone 1.0 mg/kg/day) to decrease the risk of severe side effects, chronicization, and disease-related hospitalizations (class IIa, LOE B) [24]. Additional immunosuppressive therapies are based on less evidence based data and should be considered only for true refractory cases also after failure of combined therapies with aspirin or a NSAID, colchicine and a corticosteroid [21, 23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree