4 Acquired Heart Disease

In this chapter, primary myocardial disease (hypertrophic, dilated, and restrictive cardiomyopathy), cardiovascular infections (myocarditis, infective endocarditis), and acute rheumatic fever will be presented.

I. PRIMARY MYOCARDIAL DISEASE (CARDIOMYOPATHY)

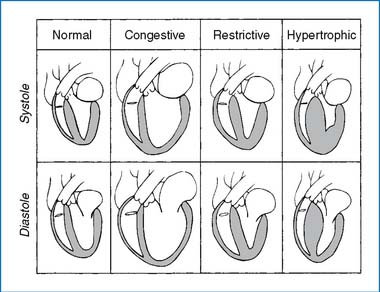

Primary myocardial disease affects the heart muscle itself and is not associated with congenital, valvular, or coronary heart disease or systemic disorders. Cardiomyopathy has been classified into three types on the basis of anatomic and functional features: (1) hypertrophic, (2) dilated (or congestive), and (3) restrictive (Fig. 4-1). The three types of cardiomyopathies are functionally different from one another, and the demands of therapy are also different.

A. HYPERTROPHIC CARDIOMYOPATHY

In about 30% to 60% of cases, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy appears to be genetically transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait; in the remainder, it occurs sporadically. It may be seen in children with LEOPARD syndrome (see Table 1-1).

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

1. A massive ventricular hypertrophy is present. Although asymmetric septal hypertrophy (ASH), formerly known as idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis (IHSS), is the most common type, a concentric hypertrophy with symmetric thickening of the left ventricle (LV) sometimes occurs. Occasionally an intracavitary obstruction may develop during systole, partly because of systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve against the hypertrophied septum, called hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM).

2. The myocardium itself has an enhanced contractile state, but diastolic ventricular filling is impaired because of abnormal stiffness of the LV. This may lead to left atrium (LA) enlargement and pulmonary venous congestion, producing congestive symptoms (exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea).

3. A unique aspect of HOCM is the variability of the degree of obstruction from moment to moment. The obstruction to LV output worsens when LV volume is reduced (as seen with positive inotropic agents, reduced blood volume, lowering of systemic vascular resistance [SVR], and so on). The obstruction lessens when the LV systolic volume increases (negative inotropic agents, leg raising, blood transfusion, increasing SVR, and so on). About 80% of LV stroke volume occurs in the early part of systole when little or no obstruction exists, resulting in a sharp upstroke of arterial pulse.

4. Anginal chest pain, syncope, and ventricular arrhythmias may lead to sudden death.

5. Infants of diabetic mothers develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with or without left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction in 10% to 20% of cases.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. Some 30% to 60% of cases are seen in adolescents and young adults with positive family history. Easy fatigability, dyspnea, palpitation, or anginal chest pain may be the presenting complaint.

2. A sharp upstroke of the arterial pulse is characteristic. A late systolic ejection murmur may be audible at the middle and lower left sternal border (LSB) or at the apex. A holosystolic murmur (of mitral regurgitation [MR]) is occasionally present. The intensity and even the presence of the heart murmur vary from examination to examination.

3. The ECG may show left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), ST-T changes, abnormally deep Q waves with diminished or absent R waves in the left precordial leads (LPLs), and arrhythmias.

4. Chest x-ray (CXR) films may show mild LV enlargement with globular heart.

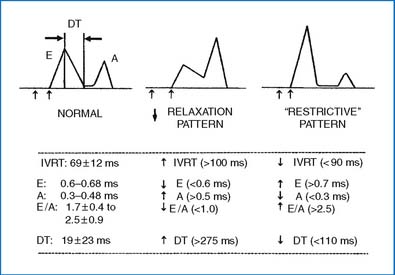

5. Echo demonstrates hypertrophy of the septum (ASH) and/or the LV free wall. In obstructive type, SAM of the mitral valve may be demonstrated. The Doppler examination of the mitral inflow demonstrates a decreased E velocity, an increased A velocity, and a decreased E/A ratio (Fig. 4-2).

MANAGEMENT

2. A β-adrenergic blocker (such as propranolol, atenolol, or metoprolol) or a calcium channel blocker (principally verapamil) is the drug of choice in the obstructive subgroup. These drugs reduce the degree of obstruction, decrease the incidence of anginal pain, and have antiarrhythmic actions. Prophylactic therapy with either β-adrenergic blockers or verapamil is controversial in patients without LVOT obstruction. In infants of diabetic mothers, β-adrenergic blockers are used when the LVOT obstruction is present. In most of these infants the hypertrophy spontaneously resolves within the first 6 to 12 months of life.

3. The following drugs are contraindicated: digitalis, other inotropic agents, and vasodilators tend to increase LVOT obstruction; diuretics may reduce LV volume and increase LVOT obstruction (but may be used in small doses to improve respiratory symptoms).

4. Morrow’s myotomy-myectomy or percutaneous alcohol ablation may be considered for drug-refractory patients with LVOT obstruction.

5. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) has been proved to be effective in preventing sudden death. The following are risk factors for sudden death in HCM and may be indications for an ICD.

6. Dual-chamber pacing tends to reduce the LVOT pressure gradient.

B. DILATED (CONGESTIVE) CARDIOMYOPATHY

Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most common form of cardiomyopathy. The idiopathic type is most common (>60%), followed by familial cardiomyopathy, active myocarditis, and other causes. It may be the end result of myocardial damage produced by a variety of infectious, toxic, or metabolic agents or immunologic disorders. Many cases of unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy may, in fact, result from subclinical myocarditis. Other causes of dilated cardiomyopathy include hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, excessive catecholamines, hypocalcemia, mucopolysaccharidosis, and nutritional disorders (kwashiorkor, beriberi, carnitine deficiency). Cardiotoxic agents (doxorubicin) also can cause dilated cardiomyopathy.

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

1. In dilated cardiomyopathy a weakening of systolic contraction is associated with dilation of all four cardiac chambers. Dilation of the atria is in proportion to ventricular dilation.

2. Intracavitary thrombus formation is common in the apical portion of the ventricular cavities and in atrial appendages, and it may give rise to pulmonary and systemic embolization.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. Fatigue, weakness, and symptoms of left heart failure (e.g., dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea) may be present.

2. On physical examination, signs of congestive heart failure (CHF) (e.g., tachycardia, pulmonary crackles, weak pulses, distended neck veins, hepatomegaly) may be present. A prominent S3 with or without gallop rhythm is present. A soft systolic murmur of MR or tricuspid regurgitation (TR) may be audible.

3. Sinus tachycardia, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), and ST-T changes are common ECG findings.

4. CXR films show generalized cardiomegaly, often with signs of pulmonary venous congestion.

5. Echo studies are diagnostic, and there may be unexpected findings in an asymptomatic patient. The LV and right ventricle (RV) are dilated with a reduced fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF). Intracavitary thrombus and pericardial effusion may be present. The mitral inflow Doppler tracing demonstrates a reduced E velocity and a decreased E/A ratio (Fig. 4-2).

6. Progressive deterioration is the rule rather than the exception. About two thirds of these patients die of arrhythmias, systemic or pulmonary embolization, or CHF within 4 years of the onset of symptoms.

MANAGEMENT

1. CHF is treated with digoxin, diuretics (furosemide, spironolactone), ACE inhibitors (captopril, enalapril), bed rest, and restriction of activity. Critically ill patients may require intubation, mechanical ventilation, and administration of rapidly acting inotropic agents (dobutamine, dopamine).

2. Antiplatelet agents (aspirin) should be initiated. Anticoagulation with warfarin may be indicated. If thrombi are detected, they should be treated aggressively with heparin initially and later switched to long-term warfarin therapy.

3. Patients with arrhythmias may be treated with amiodarone or other antiarrhythmic agents. Amiodarone is effective and relatively safe in children. For symptomatic bradycardia a cardiac pacemaker may be necessary. An ICD may be considered.

4. The beneficial effects of β-adrenergic blocking agents (somewhat unorthodox, given poor contractility) have been reported in adult and pediatric patients. Carvedilol is a β-adrenergic blocker with additional vasodilating action. Recent evidence suggests that activation of the sympathetic nervous system may have deleterious cardiac effects rather than being an important compensatory mechanism as traditionally thought.

5. If carnitine deficiency is considered the cause of the cardiomyopathy, carnitine supplementation should be started.

6. A preliminary report suggests that administration of recombinant human growth hormone (0.025 to 0.04 mg/kg/day for 6 months) may improve LV ejection fraction, increase LV wall thickness, reduce the chamber size, and improve cardiac output.

7. Many of these children may become candidates for cardiac transplantation.

D. DOXORUBICIN CARDIOMYOPATHY

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY

1. Doxorubicin cardiomyopathy is becoming the most common cause of chronic CHF in children. Its prevalence is nonlinearly dose related, occurring in 2% to 5% of patients who have received a cumulative dose of 400 to 500 mg/m2 and up to 50% of patients who have received more than 1000 mg/m2 of doxorubicin (Adriamycin).

2. Risk factors for the cardiomyopathy include age younger than 4 years and a cumulative dose exceeding 400 to 600 mg/m2. A dosing regimen with larger and less frequent doses has been raised as a risk factor but not proved.

3. Dilated LV, decreased contractility, and elevated LV filling pressure are present.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. Patients have a history of receiving doxorubicin, with the onset of symptoms 2 to 4 months, and rarely years, after completion of therapy.

2. Patients are usually asymptomatic until signs of CHF develop. Tachypnea and dyspnea made worse by exertion are the usual presenting complaints.

3. Signs of CHF may be present on physical examination.

4. CXR films show cardiomegaly with or without pulmonary congestion or pleural effusion.

5. The ECG frequently shows sinus tachycardia with occasional ST-T changes.

6. Echo studies reveal slightly increased LV size, reduced LV wall thickness, and decreased ejection fraction or fractional shortening.

7. Symptomatic patients have a high mortality rate. The 2-year survival rate is about 20%, and almost all patients die by 9 years after the onset of the illness.

MANAGEMENT

1. Attempts to reduce anthracycline cardiotoxicity have been made in three directions: (a) anthracycline dose limitation, (b) developing less cardiotoxic analogs, and (c) concurrently administering cardioprotective agents to attenuate the cardiotoxic effects of anthracycline to the heart.

2. In symptomatic patients, the following medications are used.

3. Cardiac transplantation may be an option for selected patients.

F. RESTRICTIVE CARDIOMYOPATHY

PREVALENCE, PATHOLOGY, AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

1. Restrictive cardiomyopathy is the least common of the three types of cardiomyopathy, occurring in 5% of cardiomyopathy cases in children.

2. The condition is characterized by an abnormal diastolic ventricular filling owing to excessively stiff ventricular walls, often caused by infiltrative disease processes (e.g., sarcoidosis, amyloidosis). The ventricles remain normal in size and maintain normal contractility, but the atria are enlarged out of proportion to the ventricles.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. History of exercise intolerance, weakness and dyspnea, or chest pain may be present.

2. Jugular venous distention, gallop rhythm, and a systolic murmur of MR or TR may be present.

3. CXR films show cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, and pleural effusion.

4. The ECG may show atrial fibrillation and paroxysms of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

5. Echo studies reveal characteristic biatrial enlargement, with normal cavity size of the LV and RV. LV systolic function (ejection fraction) is normal until the late stages of the disease. Atrial thrombus may be present.

MANAGEMENT

1. Diuretics are beneficial by relieving congestive symptoms. Digoxin is not indicated because systolic function is unimpaired. ACE inhibitors may reduce systemic BP without increasing cardiac output, and therefore should probably be avoided.

2. Calcium channel blockers may be used to increase diastolic compliance.

3. Anticoagulants (warfarin) and antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and dipyridamole) may help prevent thrombosis.

4. Permanent pacemaker is indicated for complete heart block.

II. CARDIOVASCULAR INFECTIONS

A. INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS (SUBACUTE BACTERIAL ENDOCARDITIS)

PATHOGENESIS AND PATHOLOGY

1. Two factors are important in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis: (a) structural abnormalities of the heart or great arteries with a significant pressure gradient or turbulence, with resulting endothelial damage and platelet-fibrin thrombus formation and (b) bacteremia, even if transient, with adherence of the organisms and eventual invasion of the cardiac tissue.

2. Those with a prosthetic heart valve or prosthetic material in the heart are at particularly high risk for infective endocarditis. Drug addicts may develop endocarditis in the absence of known cardiac anomalies.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

1. Most patients are known to have an underlying heart disease. The onset is usually insidious with prolonged low-grade fever (101° F to 103° F) and various somatic complaints.

2. Heart murmur is almost always present, and splenomegaly is common (70%).

3. Skin manifestations (50%) may be present in the following forms.

4. Embolic or immunologic phenomena in other organs are present in 50% of cases.

6. Echocardiography. Although standard transthoracic echo (TTE) is sufficient in most cases, transesophageal echo (TEE) may be needed in obese or very muscular adolescents.

DIAGNOSIS.

The diagnosis of infective endocarditis is challenging. The modified Duke criteria are used in the diagnosis. There are three categories of diagnostic possibilities using the modified Duke criteria: definite, possible, and rejected. A diagnosis of “definite” IE is made either by pathologic evidence or fulfillment of certain clinical criteria (Box 4-1). Box 4-2 shows definitions of major and minor clinical criteria.

BOX 4-1 DEFINITION OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS ACCORDING TO THE MODIFIED DUKE CRITERIA

From Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS et al: Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association, Circulation 111(23):e394-e433, 2005.

BOX 4-2 DEFINITION OF MAJOR AND MINOR CLINICAL CRITERIA FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

MAJOR CRITERIA

A. BLOOD CULTURE POSITIVE FOR IE

1. Typical microorganisms consistent with IE from two separate blood cultures: Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus bovis, HACEK group, Staphylococcus aureus, or community-acquired enterococci in the absence of a primary focus

2. Microorganisms consistent with IE from persistently positive blood cultures defined as follows: at least two positive cultures of blood samples drawn >12 hr apart, or all of three or a majority of at least four separate cultures of blood (with first and last sample drawn at least 1 hr apart)

3. Single positive blood culture for Coxiella burnetii or antiphase-1 IgG antibody titer >1:800

B. EVIDENCE OF ENDOCARDIAL INVOLVEMENT

1. Oscillating intracardiac mass on valve or supporting structures, in the path of regurgitant jets, or on implanted material in the absence of an alternative anatomic explanation; or

3. New partial dehiscence of prosthetic valve; or

4. New valvular regurgitation (worsening or changing or preexisting murmur not sufficient)

MINOR CRITERIA

1. Predisposition, predisposing heart condition, or injection drug users

3. Vascular phenomena: major arterial emboli, septic pulmonary infarcts, mycotic aneurysm, intracranial hemorrhage, conjuctival hemorrhages, and Janeway lesions

4. Immunologic phenomena: glomerulonephritis, Osler nodes, Roth spots, and rheumatoid factor

5. Microbiologic evidence: positive blood culture but does not meet a major criterion as noted previously* or serologic evidence or active infection with organisms consistent with IE

From Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS et al: Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association, Circulation 111(23):e394-e433, 2005.

MANAGEMENT

1. Blood cultures are indicated for all patients with fever of unexplained origin and a pathologic heart murmur, a history of heart disease, or previous endocarditis.

2. Consultation from a local infectious disease specialist is highly recommended.

3. Initial empirical therapy is started with the following antibiotics while awaiting the results of blood cultures.

4. The final selection of antibiotics for native valve IE depends on the organism isolated and the results of an antibiotic sensitivity test.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree