You may encounter situations in which it’s difficult to apply the general guidelines presented in an algorithm. Such special situations require you to modify the general guidelines to increase your chance of successfully resuscitating the patient. These situations include acute stroke, pregnancy, trauma, submersion or drowning, electric shock or lightning strike, hypothermia, toxicologic emergencies, near-fatal asthma, and anaphylaxis. In addition, lifethreatening electrolyte disturbances are frequently associated with cardiac arrest. Sereve electrolyte disturbances may be the cause of cardiac arrest or complicate resuscitation efforts during cardiac arrest from other causes. (See

Managing electrolyte disturbances associated with cardiac arrest,

pages 254 to 255.)

As with all emergencies, investigation into the background of the injury may be essential to treat the patient. For example, treatment measures for stroke are dependent on the amount of time that has elapsed since the onset of symptoms. Likewise, in toxicologic emergencies, knowledge of the specific drug or substance ingested helps to determine antidotal treatment.

Acute stroke

Acute stroke is a sudden impairment of cerebral circulation in one or more of the blood vessels supplying the brain. Stroke interrupts or diminishes oxygen supply and commonly causes serious damage or necrosis in brain tissues.

Playing the odds

About 85% of strokes are ischemic, resulting from thrombus formation in a blood vessel supplying the brain or from embolism (typically from the heart or carotid artery). Other strokes are hemorrhagic, resulting from the rupture of a cerebral artery or aneurysm.

The sooner, the better

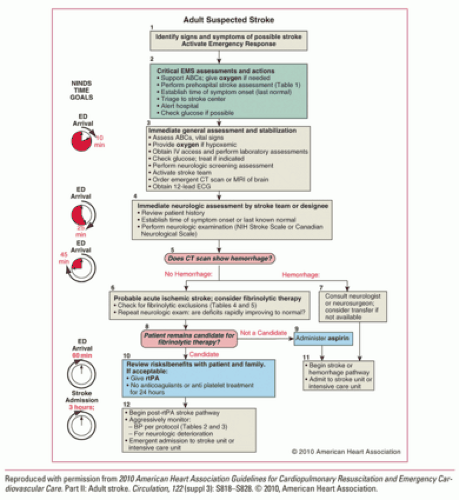

The sooner normal blood flow is restored to the brain after a stroke, the better the patient’s chance for recovery. A catch phrase that is commonly used is “time is brain.” Therefore, prompt recognition and treatment of stroke can limit the extent of damage and significantly improve the patient’s outcome. The National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has established guidelines for the completion of tasks beginning from the minute the patient arrives in the emergency department (ED).

What causes it

Some strokes are caused by an arrhythmia (particularly atrial fibrillation) or a hypertensive crisis. In many cases, no precipitating event is identified. The risk of stroke is increased in patients with a history of:

transient ischemic attacks (TIAs)

atherosclerosis

hypertension

arrhythmias

diabetes mellitus

heart disease

cigarette smoking

hormonal contraceptive use

personal or family history of stroke

hypercoagulative state

sickle cell disease

carotid artery disease.

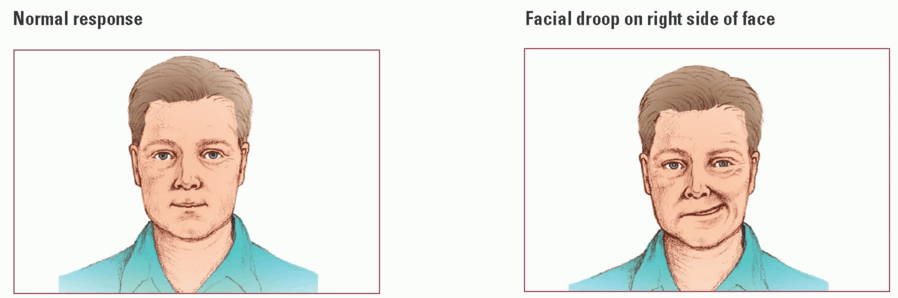

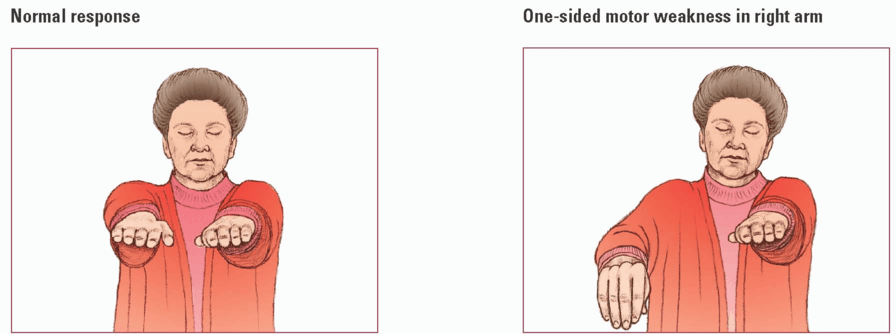

What to look for

Signs and symptoms of stroke vary with the artery affected (and, consequently, the portion of the brain it supplies), severity of damage, and extent of collateral circulation that develops to help the brain compensate for decreased blood supply.

Common signs and symptoms of stroke include the sudden onset of:

hemiparesis on the affected side to unilateral or bilateral paralysis of the extremities

unilateral sensory defect (such as numbness, tingling, or abnormal sensation), typically on the same side as the hemiparesis or hemiplegia

slurred or indistinct speech or the inability to understand speech

loss of half of the field of vision to the same side in both eyes, double vision, or transient vision loss in one eye (usually described as a shade coming down)

mental status changes or loss of consciousness (particularly if associated with at least one of the above symptoms)

severe headache (seen with hemorrhagic stroke).

How it’s treated

For all patients with signs and symptoms of stroke:

Maintain a patent airway and adequate oxygenation (oxygen saturation greater than 94%).

Monitor for and treat hypoglycemia or marked hyperglycemia (serum glucose level of 185 mg/dL or less).

Monitor blood pressure and manage it based on these considerations:

If the patient is a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy, keep his blood pressure below 185 mm Hg systolic or 110 mm Hg diastolic to minimize the risk of bleeding complications.

If the patient isn’t a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy, treat only a severely elevated blood pressure (systolic blood pressure greater than 220 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure greater than 120). Inducing lower perfusion pressures may increase ischemia and worsen the stroke.

Stroke Chain of Survial

As with the adult chain of survival for victims of cardiac arrest, remember the eight D’s (links in the chain) to help minimize brain injury and maximize recovery.

detection

dispatch

delivery

door

data

decision

drug

Detection

Early detection of the signs and symptoms of stroke helps ensure the best outcome. A patient presenting with signs of stroke, such as difficulty talking or unresponsiveness, needs to be differentiated from other emergencies. For example, a patient with a low blood sugar may present with slurred speech or altered level of consciousness (LOC). A rapid blood sugar analysis can rule out hypoglycemia as a cause. If low blood sugar is the cause, rapid treatment should be initiated. Also, the quicker a patient suffering a stroke is evaluated and diagnosed, the faster he may qualify for certain treatments such as fibrinolytic therapy.

Dispatch

You must notify emergency medical service (EMS) personnel at the earliest signs of stroke to ensure a quick response. A patient with suspected stroke should receive the same priority as a patient experiencing an acute myocardial infarction (MI). The 911 dispatcher is trained to ask specific questions of the caller to determine what type of emergency is occurring and alert the EMS team as to how to respond.

Primary priority

For a patient presenting with signs and symptoms of stroke, assess and manage his airway, breathing, and circulation, and intervene if necessary to provide cardiopulmonary support. Follow these steps:

First, assess the patient for a head or neck injury because a fall may have accompanied the stroke. If indicated, apply a cervical collar and logroll the patient to prevent further injury. (Cervical spinal X-rays may be ordered in the ED.)

Position the patient in the recovery position to prevent aspiration.

Suction the airway as necessary to ensure patency because paralysis of the tongue, mouth, and throat commonly causes partial or complete airway obstruction, hampering the patient’s ability to clear secretions. Aspiration is also possible.

If the patient’s breathing pattern is abnormal, you may need to insert an advanced airway. You may also need to provide ventilatory assistance through a bag-mask device. (Breathing patterns are typically normal except when the patient is comatose.) Administer oxygen to keep oxygen saturation at greater than 94%.

Apply a portable cardiac monitor. (Cardiac arrest is uncommon except in cases of intracranial hemorrhage; however, you may detect underlying cardiac arrhythmias on the monitor. If cardiac arrest occurs, begin cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR].)

Check the patient’s blood glucose level, but don’t delay transport for further assessment.

Critical interval

After completing the initial assessment, attempt to establish the time of the patient’s onset of symptoms. The interval between the onset of symptoms and the initiation of treatment is critical. If no one is able to identify when the patient’s symptoms began, the onset of symptoms is defined as the last time the patient was observed to be normal.

The patient should be transported to a stroke-prepared hospital, primary stroke center, or comprehensive stroke center. Studies show that patients admitted to dedicated stroke units have a greater chance of improved functional outcomes. Facilities with established stroke programs have protocols that may establish a diagnosis of stroke more quickly than a facility without one. Remember that communicating with the receiving facility while the patient is en route is critical to ensuring prompt action in the ED when the patient arrives.

Door

As soon as the patient comes through the door of the ED (within 10 minutes), rapid assessment and evaluation of baseline vital signs should begin. The patient should be evaluated to determine if he’s a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy. At this time, complete the secondary assessment. Follow these steps:

Reassess the patient’s airway and breathing.

If the patient is breathing adequately without assistance, administer oxygen to keep his saturation at greater than 94%.

Reassess circulation, assess blood pressure, and evaluate cardiac rhythm.

Make sure that I.V. access has been established.

Obtain appropriate laboratory studies (including blood glucose level, CBC, and cogqulation studies) and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). (Don’t delay the computed tomography [CT] scan to obtain the ECG.)

Assess the patient’s neurologic status to determine the extent of his deficits using a standardized tool such as the NIH Stroke Scale. (For a patient with a subarachnoid hemorrhage, you may use the Hunt and

Hess Scale to evaluate stroke severity. This scale may also help predict the patient’s risk of complications and chance of survival.)

Obtain a CT scan without contrast medium within 25 minutes of the patient’s arrival in the ED. (The results should be available within 45 minutes of patient arrival to determine whether a subarachnoid hemorrhage is present.)

Institute continuous cardiac monitoring.

Just to be sure

During the first few hours after an ischemic stroke, the CT scan may not show signs of ischemia. Those with a subarachnoid hemorrhage will have a normal CT scan only about 5% of the time. If you suspect a subarachnoid hemorrhage despite a normal CT scan, a lumbar puncture should be performed. Fibrinolytic therapy is contraindicated in patients who have experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Data

Data, such as your assessment, patient history, vital signs, and CT scan results, help the neurosurgical team determine the best treatment plan for the patient. If the patient has signs of brain hemorrhage and a neurosurgical team isn’t available, consider transferring the patient to another facility that can offer him the appropriate neurologic support.

Decision

The type of treatment you provide is based on the assessment parameters and the patient’s situation and type of injury.

Fibrinolytic therapy is indicated for acute ischemic stroke if it can be initiated within the first 3 hours of symptom onset.

Emergency angiography may be necessary if the patient has a subarachnoid hemorrhage.

If an aneurysm is present, treatment may include aneurysm clipping, coiling, or exclusion; administering nimodipine; and correcting hyponatremia and water loss (if diabetes insipidus develops).

If intracerebral hemorrhage is present, treatment may include preventing continued bleeding, managing intracranial pressure (ICP) and, possibly, neurosurgical decompression.

Maybe, maybe not

Hypertension is commonly seen in stroke patients as a result of stress from the stroke and usually resolves without treatment. Avoid using typical treatments for hypertension because hypotension may result, which can impair cerebral perfusion.

Elevated blood pressure after a stroke isn’t a hypertensive emergency unless the patient has other medical conditions. The occurrence of acute MI, severe left ventricular dysfunction, aortic dissection, or hypertensive encephalopathy indicates a need to maintain more normal blood pressure.

Push or drip? It’s all good!

Appropriate antihypertensives for the stroke patient who’s a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy include labetalol (Trandate) or nicardipine (Cardene).

Administer labetalol 10 to 20 mg by I.V. push over 1 to 2 minutes; may repeat once.

Start nicardipine infusion at 5 mg/hour and titrate by 2.5 mg/hour every 5 to 15 minutes (maximum, 15 mg/hour).

Disposition

Patients should be admitted to a specialized stroke unit or criticalcare unit quickly (within 3 hours of arrival is recommended).

Studies show that care delivered in a stroke unit is higher quality than in general medical units and the positive effects of that care can persist for years.

What to consider

If the patient has a fever, use acetaminophen (Tylenol) or other cooling measures to reduce hyperthermia.

If seizures occur, administer anticonvulsants

If you suspect cerebral edema (clinically significant in only 10% to 20% of stroke patients), you must maintain ICP sufficient for adequate cerebral perfusion but low enough to avoid brain herniation. Treatments may include:

Just the facts

Just the facts