We tested the hypothesis that morphologic lesion assessment helps detect acute coronary syndrome (ACS) during index hospitalization in patients with acute chest pain and significant stenosis on coronary computed tomographic angiogram (CTA). Patients who presented to an emergency department with chest pain but no objective signs of myocardial ischemia (nondiagnostic electrocardiogram and negative initial biomarkers) underwent CT angiography. CTA was analyzed for degree and length of stenosis, plaque area and volume, remodeling index, CT attenuation of plaque, and spotty calcium in all patients with significant stenosis (>50% in diameter) on CTA. ACS during index hospitalization was determined by a panel of 2 physicians blinded to results of CT angiography. For lesion characteristics associated with ACS, we determined cutpoints optimized for diagnostic accuracy and created lesion scores. For each score, we determined the odds ratio (OR) and discriminatory capacity for the prediction of ACS. Of the overall population of 368 patients, 34 had significant stenosis and 21 of those had ACS. Scores A (remodeling index plus spotty calcium: OR 3.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2 to 10.1, area under curve [AUC] 0.734), B (remodeling index plus spotty calcium plus stenosis length: OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.6 to 13.7, AUC 0.824), and C (remodeling index plus spotty calcium plus stenosis length plus plaque volume <90 HU: OR 3.4, 95% CI 1.5 to 7.9, AUC 0.833) were significantly associated with ACS. In conclusion, in patients presenting with acute chest pain and stenosis on coronary CTA, a CT-based score incorporating morphologic characteristics of coronary lesions had a good discriminatory value for detection of ACS during index hospitalization.

In previous studies coronary computed tomographic (CT) angiographic imaging of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and with stable angina has demonstrated morphologic differences of segments with significant stenosis. Morphologic characteristics such as positive remodeling, spotty calcium, larger plaque area and volume, presence of low CT attenuation plaque, and appearance of peripheral contrast rim were more frequent in patients with ACS. We studied whether the detection of previously identified characteristics of culprit lesions in patients with acute chest pain and significant stenosis on coronary CT angiogram (CTA) in the absence of objective evidence of myocardial ischemia or necrosis at the initial evaluation would permit discrimination of those with from those without ACS during index hospitalization.

Methods

A description of the patient population in the present study was reported recently. A convenience sample of low- to intermediate-risk patients presenting to an emergency department with a chief complaint of chest discomfort and clinical suspicion for ACS but who had normal initial troponin and an initial electrocardiogram without evidence of myocardial ischemia was enrolled. ACS was defined as acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris during index hospitalization according to American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology guidelines. Unstable angina pectoris was defined as clinical symptoms suggestive of ACS (typical chest discomfort or equivalent with an unstable pattern of chest pain, i.e., at rest, new onset, or crescendo angina) in the absence of increased troponin coinciding with appropriate objective evidence of myocardial ischemia on stress perfusion imaging or coronary angiogram demonstrating >50% coronary stenosis. To establish the diagnosis of ACS, an outcome panel of 2 experienced physicians blinded to CT findings reviewed the patient data. Disagreement was resolved by consensus, which included an additional senior cardiologist. We collected information on cardiovascular risk profile and Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score. For the present analysis, we included all patients with definitive significant stenosis (>50% in diameter) on coronary CTA by qualitative assessment. The institutional review board approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

All patients were scanned using a 64-row CT scanner (Sensation 64; Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). Intravenous β blocker (metoprolol 5 to 20 mg) was administered in all patients with a heart rate >60 beats/min. All patients received sublingual nitroglycerin 0.6 mg. Contrast agent (Iodixanol 320 g/cm 3 ; Visipaque, General Electric Healthcare, Princeton, New Jersey) was injected at a rate of 5 ml/s. Scan parameters were 64- × 0.6-mm detector configuration, 330-ms gantry rotation time, 120-kV tube potential, 850-mA effective tube current–time product, and electrocardiography-based tube current modulation. Axial images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.75 mm using a retrospectively electrocardiographically gated reconstruction.

Coronary CT angiographic datasets were transferred to an off-line workstation (Vitrea, Vital Images, Minnetonka, Minnesota). An independent reader (>3 years of cardiac CT experience) reviewed all studies and selected the series in cardiac phase with the best image quality in each subject for further analysis. The reader determined the culprit lesion in each patient with ACS using previously described rules. In patients with ACS and 1 significant lesion, this lesion was considered the culprit lesion. In patients with ACS and multiple significant lesions, we used information from diagnostic testing (electrocardiography, nuclear perfusion imaging, and invasive coronary angiography) to determine the culprit vessel. If there were >1 significant lesion in this vessel, the lesion with the most severe stenosis was analyzed. In patients without ACS, the lesion with the most severe stenosis by CT angiography was analyzed.

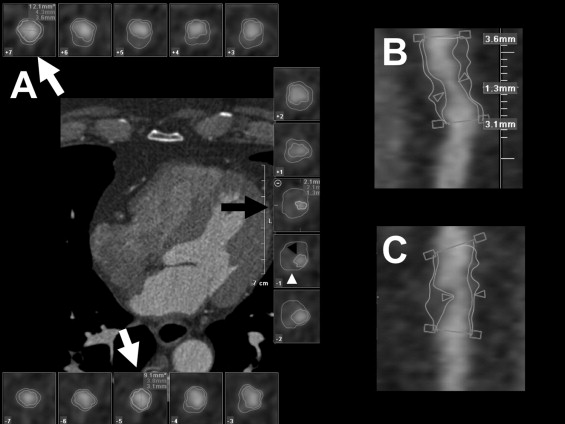

Two independent readers blinded to demographic information and presence of ACS evaluated the CT dataset for characteristics of significant lesions. Each vessel containing significant stenosis was analyzed in curved multiplanar reformatted images in long-axis and cross-sectional views. For each lesion, the proximal and distal references were determined ( Figure 1 ) . We used semiautomated software (Vessel Probe, Vitrea, Vital Images) to segment the lumen and outer vessel boundaries in all coronary artery cross sections between the proximal and distal references ( Figure 1 ). If necessary, boundaries were manually adjusted. The lumen boundary was defined as the transition from a high-attenuation coronary lumen filled with contrast agent to intermediate attenuation of noncalcified atherosclerotic plaque or high attenuation of calcified plaque. The outer vessel boundary was defined as the transition from an intermediate attenuation on noncalcified plaque or high attenuation of calcified plaque to a low attenuation of perivascular fat.

Diameters at the site of maximum stenosis and at proximal and distal references were measured ( Figure 1 ). Degree of stenosis was calculated as the ratio of the difference between the diameter at maximum stenosis and the mean of diameters at the proximal and distal references divided by the mean of diameters at proximal and distal references and expressed as percentage. Remodeling index was calculated as the outer vessel area at the site of maximum stenosis divided by the mean of outer vessel areas at proximal and distal references. Positive remodeling was defined as a remodeling index >1.05. Plaque length was measured as the length of the coronary segment between the proximal and distal references on curved multiplanar reformatted images. Stenosis length was measured as the length of the visually significantly narrowed segment on curved multiplanar reformatted images.

Plaque volume was automatically calculated as the volume of all voxels segmented between the luminal and outer vessel boundaries on curved multiplanar reformatted images. Proximal and distal references were used as the proximal and distal ends of the plaques. We reported the total volume of plaque and volumes of plaques in the range of <30, <90, 90 to 150, and >150 HU. Composition of the plaque was assessed visually and categorized as calcified or noncalcified plaque as described previously ( Figure 2 ) . In the presence of coronary calcium, calcified plaques were further characterized as spotty calcium (discrete calcified nodules clearly surrounded by noncalcified plaque, <3 mm in diameter) and heavy calcium (confluent calcium occupying most of the vessel wall; Figure 2 ).

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as percentage (count). Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess for differences within continuous and categorical variables. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient to assess agreement of measurements between 2 observers.

In univariate analysis, characteristics of stenosis and plaque were individually evaluated for an association with ACS. We generated 3 scores (A, B, and C) based on characteristics of stenosis and plaque. Score A consisted of the 2 features previously shown to be associated with culprit lesions in ACS: positive remodeling index and spotty calcium. For additional lesion scores, continuous variables associated with the presence of the ACS at a significance level of <0.10 in univariate analysis were added according to their area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) values in univariate analysis in the descending order. Variables were dichotomized using cutpoints with the best discriminatory capacity (highest AUC) for ACS. Presence of each plaque feature increases the score by 1 point.

The discriminatory capacity of scores for prediction of ACS was assessed using c-statistics. Asymptotic 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for AUC were estimated using a nonparametric approach that is closely related to the jackknife technique. Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs for diagnosis of ACS by each score. To assess the internal validity of ACS prediction using the model scores and to adjust for overfitting/optimism, bootstrap resampling procedures were used. One hundred bootstrap samples were drawn with replacement from the original dataset. The difference of AUC from the original dataset and from the bootstrap sample (mean AUC) represented an estimate of optimism in the apparent performance. Optimism was subtracted from the apparent performance to estimate the internally validated performance and adjust for overfitting/optimism.

We used 2 × 2 tables to calculate the diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, and positive predictive value) of single score values for the presence of ACS and provided binomial 95% CIs. Pretest probability of ACS was defined as prevalence of ACS within the cohort (21 of 34). Post-test probability of ACS for all lesion scores was determined using the Bayes theorem (pretest odds multiplied by positive likelihood ratio equals post-test odds of ACS). All performed tests were 2-sided and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

The mean age of the entire Rule Out Myocardial Infarction using Computer Assisted Tomography (ROMICAT) trial population was 53 ± 12 years old; 223 (61%) were men. Of the overall study population, 31 (8%) were judged to have ACS. Overall, 34 of 368 patients (9%) had definite coronary stenosis (>50% in diameter) by coronary CT angiography. Of those 62% (21 of 34) had ACS (acute myocardial infarction, n = 5; unstable angina pectoris, n = 16). In the group of patients with ACS, 13 patients underwent cardiac catheterization, 12 patients underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, and 1 patient underwent coronary artery bypass surgery. Baseline demographics were similar in patients with and without ACS except for a lower body mass index in patients with ACS ( Table 1 ). There was also a trend toward less diabetes mellitus in the ACS group. TIMI score was similar in patients with and without ACS.

| Variable | ACS | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 21) | No (n = 13) | ||

| Age (years) | 61 (51–67) | 58 (49–65) | 0.97 |

| Men | 18 (86%) | 11 (85%) | 1.00 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 27 (25–30) | 31 (28–33) | 0.05 |

| Hypertension ⁎ | 14 (67%) | 11 (85%) | 0.43 |

| Hyperlipidemia † | 11 (52%) | 8 (62%) | 0.73 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (14%) | 6 (46%) | 0.06 |

| Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction score | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.51 |

⁎ Blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive treatment.

† Total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl or on lipid-lowering treatment.

Of 21 patients with ACS, 13 had 1 stenosis and 9 had >1 significant stenosis. Of 13 patients without ACS, 10 had 1 stenosis and 3 had >1 significant stenosis. Distribution of analyzed lesions was left anterior descending coronary artery 11 versus 7, left circumflex coronary artery 3 versus 1, and right coronary artery 7 versus 5 for ACS versus no ACS, respectively.

Table 2 presents characteristics of coronary lumen and plaque. Degree of stenosis was similar in patients with and without ACS, but length of stenosis was significantly longer in those with ACS. Length of coronary plaque and plaque cross-sectional area at the site of stenosis were not different between patients with and without ACS. Volume of plaque with CT attenuation <90 HU was larger in patients with ACS. There was also a trend toward larger volume of plaque with CT attenuation <30 HU. Positive remodeling (remodeling index >1.05) was more frequent in patients with ACS. There was a trend toward a higher frequency of spotty calcium in patients with ACS. There was good correlation for quantification of stenosis (R 2 = 0.71) and plaque volumes (total, R 2 = 0.83; <90 HU, R 2 = 0.77; 90 to 150 HU, R 2 = 0.91; >150 HU, R 2 = 0.85) between 2 observers.

| CT Characteristics of Stenosis and Plaque | ACS | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 21) | No (n = 13) | ||

| Stenosis | |||

| Degree of stenosis (%) | 73 (65–83) | 66 (56–85) | 0.64 |

| Length of stenosis (mm) | 5.4 (3.5–7.7) | 4.2 (3.0–4.5) | 0.02 |

| Plaque | |||

| Length of plaque (mm) | 15.2 (11.0–21.6) | 13.8 (11.9–18.7) | 0.67 |

| Plaque area (mm 2 ) | 13.7 (10.5–17.1) | 10.0 (6.5–18.1) | 0.11 |

| Positive remodeling index (>1.05) | 13 (62%) | 2 (15%) | 0.04 |

| Total plaque volume (mm 3 ) | 212 (126–264) | 171 (78–223) | 0.24 |

| Plaque volume by attenuation (mm 3 ) | |||

| <30 HU | 21.3 (12.9–29.4) | 12.8 (9.3–15.0) | 0.07 |

| <90 HU | 90.6 (51.3–108.6) | 48.7 (40.3–74.5) | 0.03 |

| 90–150 HU | 44.0 (29.1–59.3) | 36.4 (22.1–41.7) | 0.11 |

| >150 HU | 38.8 (23.0–111.2) | 57.1 (7.8–139.7) | 0.87 |

| Calcium | |||

| None | 5 (24%) | 5 (38%) | 0.45 |

| Spotty | 10 (48%) | 2 (15%) | 0.08 |

| Heavy | 6 (29%) | 6 (46%) | 0.29 |

We generated 3 lesions scores. Score A contained positive remodeling and spotty calcium. Score B was generated by adding the variable with the highest AUC in univariate analysis (stenosis length cutpoint 4.5 mm, AUC 0.800) to score A. Score C was generated by adding the variable with the second highest AUC in univariate analysis (low-density [<90 HU] plaque volume cutpoint 80 mm 3 , AUC 0.709) to score B. OR per lesion score unit for predicting ACS ranged from 3.4 (score C) to 4.6 (score B) and all scores were significantly associated with ACS (p <0.05; Table 3 ).