pain, mimicking renal or ureteral colic. Signs and symptoms of hemorrhage —such as weakness, sweating, tachycardia, and hypotension— may be subtle because rupture into the retroperitoneal space produces a tamponade effect that prevents continued hemorrhage. Patients with such rupture may remain stable for hours before shock and death occur, although 20% die immediately.

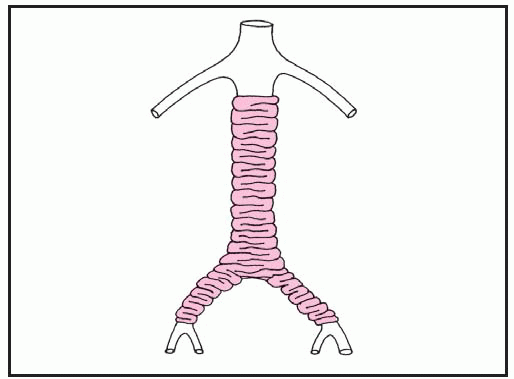

poor distal runoff, external grafting may be done.

Before surgery | After surgery |

|

|

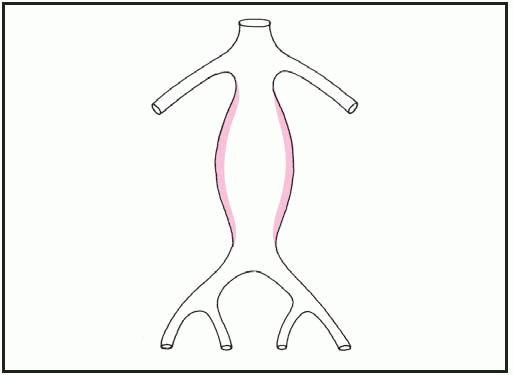

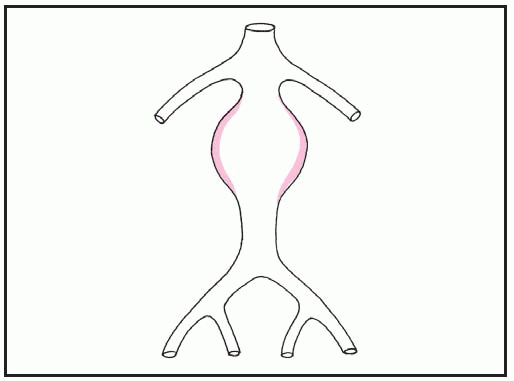

Aneurysm below renal arteries and above bifurcation | The prosthesis extends distal to the renal arteries to above the aortic bifurcation. |

Before surgery | After surgery |

|

|

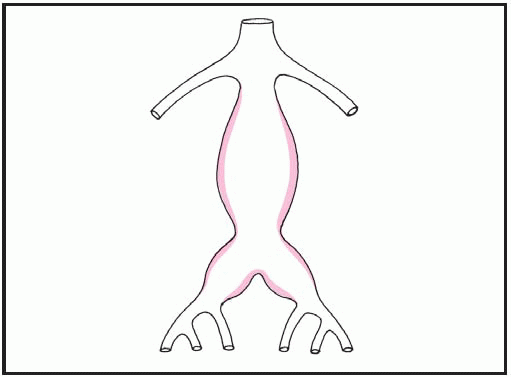

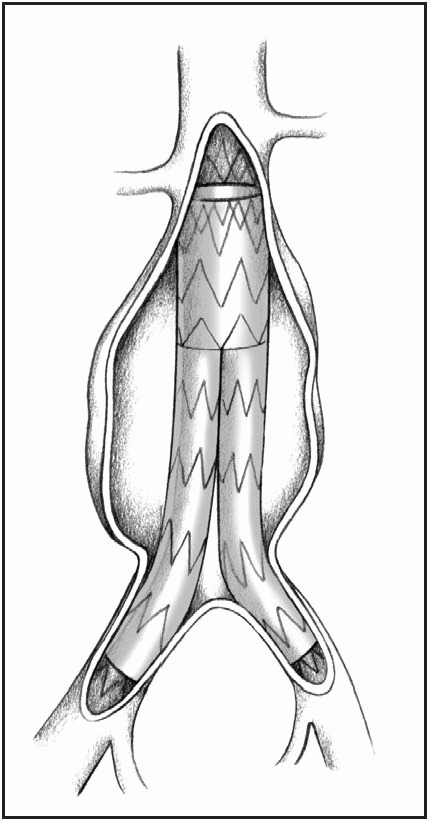

Aneurysm below renal arteries involving the iliac branches | The prosthesis extends to the common femoral arteries. |

Before surgery | After surgery |

|

|

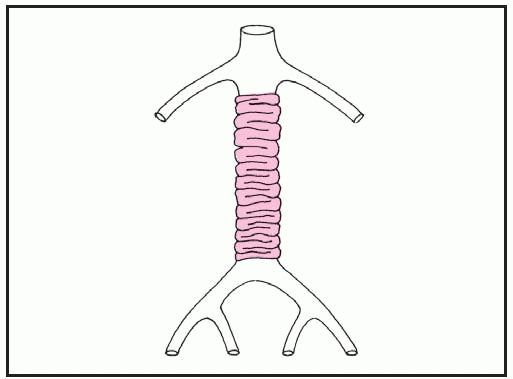

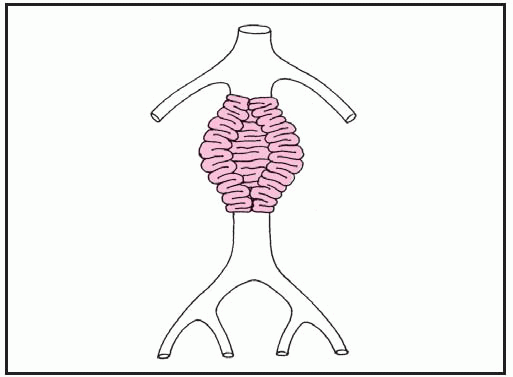

Small aneurysm in patient with poor distal runoff (poor risk) | The external prosthesis encircles the aneurysm and is held in place with sutures. |

|

resuscitative period to replace lost blood. Renal failure from ischemia is a major postoperative complication, and the patient may need hemodialysis.

some patients, the condition may be idiopathic.

Causes and incidence | Signs and symptoms | Diagnostic measures |

|---|---|---|

Aortic insufficiency | ||

▪ Results from rheumatic fever, syphilis, hypertension, or endocarditis or may be idiopathic ▪ Most common in males ▪ Associated with Marfan syndrome ▪ Associated with ventricular septal defect, even after surgical closure | ▪ Dyspnea, cough, fatigue, palpitations, angina, syncope ▪ Pulmonary venous congestion, heart failure, pulmonary edema (left-sided heart failure), “pulsating” nail beds ▪ Rapidly rising and collapsing pulses (pulsus biferiens), cardiac arrhythmias, wide pulse pressure in severe insufficiency ▪ Auscultation: reveals S3 and diastolic blowing murmur at left sternal border ▪ Palpation and visualization of apical impulse in chronic disease | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: reduced arterial diastolic pressures, aortic insufficiency, other valvular abnormalities, increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure ▪ X-ray: left ventricular enlargement, pulmonary vein congestion ▪ Echocardiography: left ventricular enlargement, changes in mitral valve movement (indirect indication of aortic valve disease), mitral thickening ▪ Electrocardiography (ECG): sinus tachycardia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and left atrial hypertrophy in severe disease |

Aortic stenosis | ||

▪ Results from congenital aortic bicuspid valve (associated with coarctation of the aorta), congenital stenosis of valve cusps, rheumatic fever, or atherosclerosis in elderly patients ▪ Most common in males | ▪ Dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, fatigue, syncope, angina, palpitations ▪ Pulmonary venous congestion, heart failure, pulmonary edema ▪ Diminished carotid pulses, decreased cardiac output, cardiac arrhythmias, possible pulsus alternans ▪ Auscultation: reveals systolic murmur at base or in carotids, possible S4 | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: pressure gradient across valve (indicating obstruction), increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressures ▪ X-ray: valvular calcification, left ventricular enlargement, pulmonary venous congestion ▪ Echocardiography: thickened aortic valve and left ventricular wall ▪ ECG: left ventricular hypertrophy |

Mitral insufficiency | ||

▪ Results from rheumatic fever, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse, myocardial infarction, severe left-sided heart failure, or ruptured chordae tendineae ▪ Associated with other congenital anomalies, such as transposition of the great arteries ▪ Rare in children without other congenital anomalies | ▪ Orthopnea, dyspnea, fatigue, angina, palpitations ▪ Peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, hepatomegaly (right-sided heart failure) ▪ Tachycardia, crackles, pulmonary edema ▪ Auscultation: holosystolic murmur at apex, split S2 (possible), S3 | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: mitral insufficiency with increased left ventricular end-diastolic volume and pressure, increased atrial pressure and pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), decreased cardiac output ▪ X-ray: left atrial and ventricular enlargement, pulmonary venous congestion ▪ Echocardiography: abnormal valve leaflet motion, left atrial enlargement ▪ ECG: left atrial and ventricular hypertrophy, sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation |

Mitral stenosis | ||

▪ Most commonly results from rheumatic fever ▪ Most common in females ▪ May be associated with other congenital anomalies | ▪ Dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, weakness, fatigue, palpitations ▪ Peripheral edema, jugular venous distention (JVD), ascites, hepatomegaly (right-sided heart failure in severe pulmonary hypertension) ▪ Crackles, cardiac arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation), signs of systemic emboli ▪ Auscultation: loud S1 or opening snap and diastolic murmur at apex | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: diastolic pressure gradient across valve, elevated left atrial pressure, PAWP greater than 15 mm Hg with severe pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary artery pressure, elevated right-sided heart pressure, decreased cardiac output, abnormal contraction of left ventricle ▪ X-ray: left atrial and ventricular enlargement, enlarged pulmonary arteries, mitral valve calcification ▪ Echocardiography: thickened mitral valve leaflets, left atrial enlargement ▪ ECG: left atrial hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, right ventricular hypertrophy, right-axis deviation |

Mitral valve prolapse syndrome | ||

▪ Cause unknown (researchers speculate that metabolic or neuroendocrine factors cause constellation of signs and symptoms) ▪ Most commonly affects young women but may occur in both sexes and in all agegroups | ▪ May produce no signs ▪ Chest pain, palpitations, headache, fatigue, exercise intolerance, dyspnea, light-headedness, syncope, mood swings, anxiety, panic attacks ▪ Auscultation: typically reveals mobile, midsystolic click, with or without mid to late systolic murmur | ▪ Two-dimensional echocardiography: prolapse of mitral valve leaflets into left atrium ▪ Color-flow Doppler studies: mitral insufficiency ▪ Resting ECG: ST-segment changes, biphasic or inverted T waves in leads II, III, AVF ▪ Exercise ECG: evaluates chest pain and arrhythmias |

Pulmonic insufficiency | ||

▪ May be congenital or may result from pulmonary hypertension ▪ Rarely, may result from prolonged use of pressure monitoring catheter in the pulmonary artery | ▪ Dyspnea, weakness, fatigue, chest pain ▪ Peripheral edema, JVD, hepatomegaly (right-sided heart failure) ▪ Auscultation: reveals diastolic murmur in pulmonic area | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: pulmonic insufficiency, increased right ventricular pressure, associated cardiac defects ▪ X-ray: right ventricular and pulmonary arterial enlargement ▪ ECG: right ventricular or right atrial enlargement |

Pulmonic stenosis | ||

▪ Results from congenital stenosis of valve cusp or rheumatic heart disease (infrequent) ▪ Associated with other congenital heart defects such as tetralogy of Fallot | ▪ May be asymptomatic or symptomatic, with dyspnea on exertion, fatigue, chest pain, syncope ▪ May lead to peripheral edema, JVD, hepatomegaly (right-sided heart failure) ▪ Auscultation: reveals systolic murmur at left sternal border, split S2 with delayed or absent pulmonic component | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: increased right ventricular pressure, decreased pulmonary artery pressure ▪ ECG: possible right ventricular hypertrophy, right-axis deviation, right atrial hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation |

Tricuspid insufficiency | ||

▪ Results from right-sided heart failure, rheumatic fever and, rarely, trauma and endocarditis ▪ Associated with congenital disorders ▪ Associated with I.V. drug abuse and infective endocarditis manifesting as tricuspid valve disease | ▪ Dyspnea and fatigue ▪ May lead to peripheral edema, JVD, hepatomegaly, and ascites (right-sided heart failure) ▪ Auscultation: reveals possible S3 and systolic murmur at lower left sternal border that increases with inspiration | ▪ Right-sided cardiac catheterization: high atrial pressure, tricuspid insufficiency, decreased or normal cardiac output ▪ X-ray: right atrial dilation, right ventricular enlargement ▪ Echocardiography: systolic prolapse of tricuspid valve, right atrial enlargement ▪ ECG: right atrial or right ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation |

Tricuspid stenosis | ||

▪ Results from rheumatic fever ▪ May be congenital ▪ Associated with mitral or aortic valve disease ▪ Most common in women | ▪ May be symptomatic with dyspnea, fatigue, syncope ▪ Possible peripheral edema, JVD, hepatomegaly, and ascites (right-sided heart failure) ▪ Auscultation: reveals diastolic murmur at lower left sternal border that increases with inspiration | ▪ Cardiac catheterization: increased pressure gradient across valve, increased right atrial pressure, decreased cardiac output ▪ X-ray: right atrial enlargement ▪ Echocardiography: leaflet abnormality, right atrial enlargement ▪ ECG: right atrial hypertrophy, right or left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree