Inpatient Surgery and Day of Admission

The majority of inpatients arrive in the hospital on the day of surgery after being preassessed and optimised prior to their admission. Day-of-surgery admission areas have developed to provide an environment away from busy wards, where pre-procedure checks can be undertaken and patients and their relatives can wait, which reduces anxiety and stress (Kulasegarah et al. 2008, Ortiga et al. 2010). Same-day admissions units (Figure 8.3) also provide the hospital with the ability to improve patient scheduling for surgery, provide a central area for clinicians to see patients on the day and improve communication with patients and their relatives. Once prepared, patients are then often walked from the unit to the operating theatre.

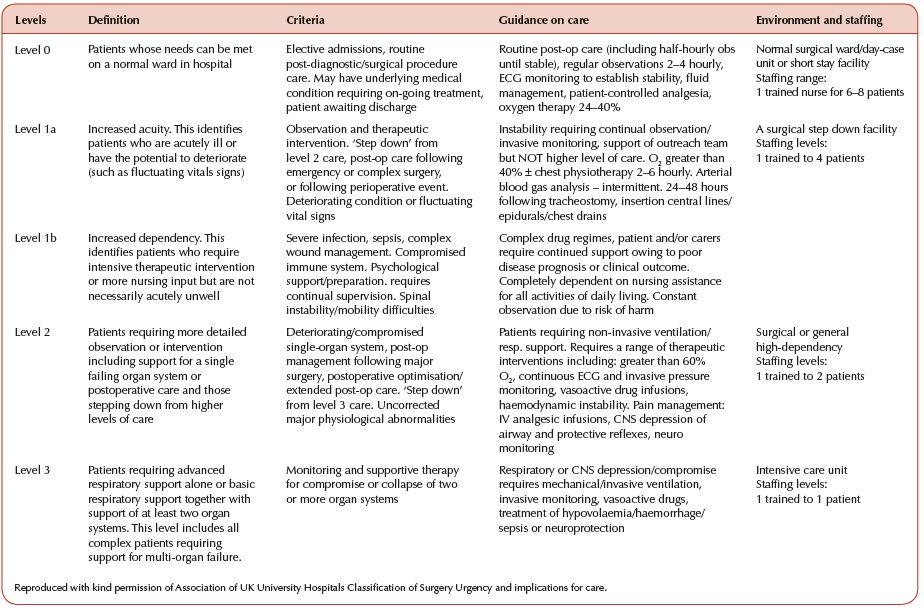

The Intensive Care Society (ICS) has highlighted a classification system for patient acuity that also indicates their place of care (Table 8.1). Acuity and dependency are important factors to understand the required staffing ratios on wards as outlined in the Association of United Kingdom University Hospitals (AUKUH) guidance, developed from the work of Hurst (2005). The AUKUH system highlights the acuity level, criteria and the types of care likely to be needed for the patient. An adapted table is outlined in Table 8.1, which also includes possible staffing levels to care for the patient.

Classification of Surgery Urgency and Implications for Care

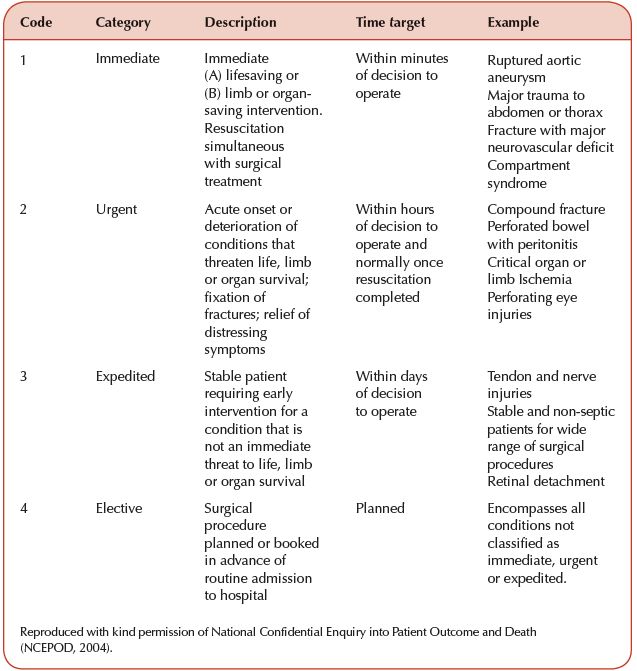

There is a requirement to risk-stratify surgery to ensure that the correct priority and preoperative care can be assigned to patients and ensure that they are operated on within a clinically appropriate timeframe. The UK system, instituted by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) in 2004 (NCEPOD 2004), identifies four main surgical priorities, as outlined in Table 8.2.

Table 8.1 Adapted levels of dependency for wards and departments.

Table 8.2 NCEPOD system of surgical classification.

Admission to the Ward or Department

The admissions process is designed to ensure that the patient is prepared safely. This process starts at the preassessment phase with a structured approach that incorporates the patient’s specific surgical and holistic needs. Prior visits to surgical units or orientation on the day can aid explanation of equipment such as nurse call-bells, bedside televisions or which staff to ask for help during their stay.

Preoperative Care Assessment

Patients are likely to have been assessed prior to admission, but an assessment of care needs is required when they arrive on the ward. These pre-procedure checks give a baseline from which risk assessments and subsequent care plans can be drawn. For example, the risks associated with developing tissue damage due to pressure in a mobile patient before the procedure may be low, however post procedure this may increase greatly. The baseline assessment needs to be completed, with a proactive care plan identified. Examples of common care assessments include:

- tissue viability – measures risk of developing pressure damage

- VTE (venous-thrombo-embolism) – measures risk of developing thrombo-emboli and associated risk of pulmonary emboli

- nutrition – particularly important aspect of surgical care as good recovery is highly dependent on nutritional status

- falls – increased risk of falls can occur postoperatively due to anaesthesia-induced disorientation, post blood loss, hypotension and unrealistic patient expectation.

The care assessment completed on admission should consider all aspects of the patient, their health needs, personal preferences, lifestyle choices and social circumstances. Consideration should be particularly given to surgical history and co-morbidities as this may impact directly on the care that they receive. A patient’s dietary preferences are also important, for example if they are a strict vegetarian and do not wish to have gelatine-based medicine capsules. Further to this, aspects of personal choice such as faith may also impact on the care delivered. For example, in caring for a Sikh patient undergoing limb amputation or Jehovah’s witnesses and blood transfusions.

The patient is central to these assessments and in the majority of cases information will be gathered from the patient themselves. Some patients may not be able to discuss these issues independently and therefore the role of the patient’s caregiver needs to be taken into consideration. When nursing a patient with dementia or learning disabilities, behavioural challenges may exist that the carer has developed mechanisms to cope with. During the care assessment it is ideal to document these so that all staff involved in caring for that patient are aware and can utilise these strategies.

Preparing for Discharge

Discharge needs to be discussed at the earliest opportunity and involve a multi-disciplinary approach to the process. This should include all aspects of the discharge from medication needs to referral to external agencies for home care. The discharge process is a time for assessment and an opportunity to listen to the patient’s concerns with an aim to reduce anxiety and stress. Advice plays a key role in the process.

Contemporary Modalities in Preoperative Care

Evidence in the literature highlights that traditional practices of surgery are often outdated, leading to the development of enhanced recovery programmes (ERP). An ERP is a systematic approach to planning and implementing a patient’s journey through elective surgery using evidence-based techniques and care protocols (Kehlet and Wilmore 2001) (Table 8.3). An ERP aims to minimise morbidity and mortality while promoting early mobilisation and normal function. These will, in turn, result in shorter lengths of stay and increased efficiency. This preoperative phase of care is seen as increasingly important in improving the patient’s perioperative care.

Table 8.3 Principles of enhanced recovery after surgery.

| Preoperative | Improved patient information and expectation Optimisation of clinical condition prior to surgery Modern fasting and nutritional management prior to surgery Same-day admission Carbohydrate loading prior to intestinal surgery |

| Intraoperative | Perioperative haemodyamic management Analgesic optimisation Minimal Invasive techniques where appropriate |

| Postoperative | Early mobilisation Early nutritional approach post surgery Revised use of drains, tubes and catheters Supported discharge |

Improved Patient Information and Expectation

The effectiveness of an ERP depends on changing patients’ expectations for their hospital stay. Modern perioperative techniques have significantly improved outcomes and reduced lengths of stay and patients should be prepared for this. To achieve a full and consistent explanation of each part of the perioperative journey it should be backed up with clear, easy-to-understand written material which helps to manage patients’ expectations. The result of this provides the patient with a better understanding of their journey, potential challenges, an achievable goal in terms of improvement and length of stay. This will also reduce the anxiety that many patients experience before surgery.

Understating the Causes of and Management of Preoperative Anxiety

McClean and Cooper (1990) suggest that anxiety begins as soon as the surgical procedure is planned and increases in intensity until it reaches maximum levels on admission (Pritchard 2009, Lee and Gin 2005). Anxiety has a number of sources including fear of the unknown, concern about pain, nausea and safety, concerns about recovery and even fears of death and dying. The impacts of this have been linked to increased need for analgesia and incidence of postoperative nausea (Moerman et al. 1996). Therefore, recognising and treating anxiety can have a great impact on the patient’s care.

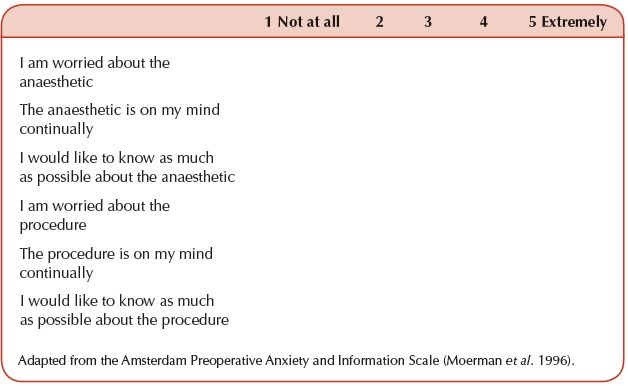

The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) (Moerman et al. 1996) was designed to assess the source of preoperative anxiety and develop a tool for alerting professionals to an individual’s risk of developing anxiety (Table 8.4).

This scale highlights that information and knowledge need to be addressed in managing preoperative anxiety. Pritchard (2009) discussed how preoperative anxiety can be managed through increasing levels of information being given to the patient. A different view was considered by Kiyohara et al. (2004) and Ivarsson et al. (2005) and by combining the two aspects of anxiety, Moerman’s scale allows for a more patient-defined management plan. Pritchard (2009) suggests multi-modal strategies, such as allowing family members to be present, reorganising investigations such as blood tests so that they are completed when patients are sedated, or using distraction techniques such as music, books and therapeutic conversation.

Table 8.4 The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree