Cleaning, as the first step in both the definition and most processes, is widely accepted as the removal of contamination from an item to the extent necessary for its further processing (and in the case of some low-risk medical devices for its intended subsequent use). Disinfection is defined in the relevant European standard for washer–disinfectors as a reduction of the number of viable microorganisms on a product to a level previously specified as appropriate for its intended further handling or use (ISO BS EN ISO 15883; International Standards Organization 2009). Sterilisation, however, has a much more rigidly described definition. Within the European standard for sterility it defines sterile as being of a state free from viable microorganisms (British Standards Institute 2001).

In practice these three distinct processes are often applied sequentially in combination with the ultimate aim of producing a sterile instrument. In some cases the first two stages alone (cleaning and disinfection) may be sufficient. The decision as to which of these processes is the final one is often made on the basis of the Spaulding Classification. The system is based on the patient’s risk for infection that various types of intervention can create. A modified form has been adopted by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in their guidance from their Microbiology Advisory Committee, commonly called the MAC manual (MHRA 2010) (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Classification of infection risk associated with the decontamination of medical devices (Spaulding 1972).

| Risk | Application of item | Recommendation |

| High |

| Sterilisation |

| Intermediate |

| Sterilisation or disinfection required Cleaning may be acceptable in some agreed evidence-based situations |

| Low |

| Cleaning |

The Need for Decontamination and Sterilisation

Decontamination is an issue of public health importance due to both concerns about preventing healthcare-associated infection and the increased focus on healthcare standards. The MHRA recently issued a device alert stating that it had received a coroner’s report which found that a patient death was caused by a failure to decontaminate a laryngoscope handle appropriately between each patient use. This led to cross-infection and subsequently septicaemia (MHRA 2011). There are undeniable links between failures in decontamination processes and patient infection.

The key to the need for decontamination lies within the definition used earlier. It says ‘make a reusable item safe for further use’ and it is this safety for reuse that drives the need. If we are to ensure that one patient’s microorganisms (no matter how benign) are not passed to another then successful decontamination is essential. In recent times minimising the risk of iatrogenic transmission of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) has brought the cleaning part of the decontamination regime into sharp focus. In 1999 the Department of Health issued a circular stating that cleaning is of the utmost importance in minimising the risk of transmitting this agent via surgical instruments (Department of Health 1999).

A Brief History of Decontamination and Sterilisation

In 1878 Robert Koch demonstrated the usefulness of steam for sterilising instruments, and by 1880 Charles Chamberland had built the first autoclave using steam under pressure. By 1960 vacuum sterilisers had become readily available, although their use for surgical instruments did not become widespread until later in the decade.

Until the mid 1960s instruments and dressings were often sterilised separately, with dressings and gowns being processed in a large dressings steriliser and instruments sterilised at the point of use and often within boiling water sterilisers. At this stage the cleaning process was manual and undertaken in a multipurpose sink. Bowie et al. (1963) published a paper describing a combined dressing and instrument tray system which they named the Edinburgh Pre-set Tray System. This is still in use in many hospitals today although most have moved to a system of pure instrument trays, with consumables and textiles supplied separately as pre-sterile items. Only a few years previously an article by Allison (1960) had outlined the work that had been undertaken in Belfast in developing a full central sterilised supply department that reprocessed everything from dressings and syringes to composite packs of theatre instruments and drapes. This became the blueprint for the future. At this stage, however, the reprocessing of single theatre instruments and bowls was still advocated within the theatre area.

By the early 1990s many hospitals had also moved the reprocessing of the remaining theatre instruments to centralised departments and had adopted the use of automated wash processes. With the publication of Health Technical Memorandum (HTM) 2030 (Department of Health 1997), the validation of cleaning and disinfection processes came to a level equivalent to that of the steriliser.

The Legislative Framework

European Directives (MDD) and the Consumer Protection Act

The European legislative framework regarding reusable surgical instruments and their reprocessing is the Medical Devices Directive MDD93/42/ECC (European Community 1993). This covers the placing on the market (not necessarily for sale or reward) of any medical devices within Europe. A number of amendments have since been introduced, the most recent being Directive 2007/47/EC (European Community 2007). The Medical Device Regulations implement the directives in UK law. The regulations have been enacted under the Consumer Protection Act 1987 and therefore there is a direct link between the reprocessing of a medical device and consumer protection. The Medical Device Directives have little technical content other than essential requirements. These make it clear that devices must not compromise the health or safety of the patient, user or any other person. The CE mark that appears on a medical device or on its packaging means that the device satisfies the relevant essential requirements and is fit for its intended purpose as specified by the manufacturer.

The Role of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in sterilisation

The Directive sets out a role in each European member state called the Competent Authority. The Competent Authority is the body responsible for implementing the requirements of the Directives in each country. In the UK, this is the MHRA. Their role is to ensure that manufacturers comply with the regulations and to evaluate adverse incident reports received from manufacturers of medical devices. Any hospital decontaminating a surgical instrument (which is a medical device) which makes that instrument available to another organisation to use would, in most cases, need to be registered with the MHRA as a manufacturer of a medical device.

Harmonised European standards

European standards that are accepted as meeting the essential requirements of the Directive are referred to as harmonised standards. Medical devices reprocessed in line with such standards will generally be presumed to comply with the relevant essential requirements in the Directive. Since the application of harmonised standards is voluntary, somebody reprocessing a surgical instrument may choose alternative methods of demonstrating compliance. For example, they may use international, national or in-house standards. Within the UK, where a robust system of national guidance around sterilisation exists, an organisation sterilising instruments may decide to use that guidance as its route to demonstrating compliance with the essential requirements. However if it does so then it should satisfy itself that the guidance does address the requirements in full.

National Standards and Compliance

Code of Practice on Healthcare Associated Infection and its impact on decontamination

In 2006 the Health Act passed into UK legislation and with it came the ‘Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Health Care Associated Infections’. Since renamed the ‘Code of Practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance’ (Department of Health 2010), it sets out a series of core requirements providing the National Framework for decontamination regulation. It stipulates that an organisation must have a lead for decontamination and for there to be a decontamination policy. It also requires that:

- decontamination of reusable medical devices takes place in appropriate facilities

- appropriate procedures are followed for the acquisition, maintenance and validation of decontamination equipment

- staff are trained in decontamination processes and hold appropriate competences for their role and

- a record-keeping regime is in place to ensure that decontamination processes are fit for purpose and use the required quality systems.

Importantly, it contains the following paragraph:

Reusable medical devices should be decontaminated in accordance with manufacturers’ instructions and current national or local best practice guidance. This must ensure that the device complies with the ‘essential requirements’ provided in the Medical Devices Regulations 2002 where applicable. This requires that the device should be clean and, where appropriate, sterilised at the end of the decontamination process and maintained in a clinically satisfactory condition up to the point of use.

The key point here is the link to the essential requirements of the MDD regardless of any mention of placing on the market or registration with the MHRA. Therefore whether a hospital sees itself as a supplier to other organisations or not, it should still meet the requirements of the Directive.

Regulation regimes including the Care Quality Commission role

The Regulated Activities Regulations 2010 (Department of Health 2010) set out the requirements for registration of a Health or Social Care provider. The Care Quality Commission, as the regulator, has the responsibility for making sure that the care that people receive meets essential standards of quality and safety. Regulation 16 (Safety, availability and suitability of equipment) requires that organisations make suitable arrangements to protect patients and others who may be at risk from the use of unsafe medical devices. The CQC have powers of enforcement to bring about improvement in poor services, or to prevent a hospital from carrying out regulated activities.

Locations for Decontamination and Sterilisation

Role of centralised departments, local decontamination, on-site/off-site

Most decontamination of invasive surgical instruments is undertaken within purpose-designed centralised departments. These departments exist with a variety of names such as centralised sterile supply departments, hospital sterilisation and disinfection units and, more recently, sterile service departments. Occasionally some hospitals may have a sterile services department located just for operating theatres and these are often called theatre sterile supply units. The abbreviation SSD is used within this chapter to mean all of these.

In general, these departments process a mixture of theatre trays, supplementary instruments and other more general packs for wards and departments. Whereas 15 years ago most departments still provided a composite tray containing a mix of instruments, swabs and consumables, the current trend is for trays to contain instruments only (with other supplies being provided either by the SSD as separately packaged pre-sterile supplies or direct by the theatre).

In 2002 the Department of Health in England embarked on a modernisation programme for decontamination (National Decontamination Programme 2003) whereby large off-site centres were procured that were operated by the private sector. These centres were typically located away from the hospital and served between 2 and 12 hospitals. They have become known as supercentres. The Theatre Support Pack (National Decontamination Programme 2009) provides advice on using an off-site service.

Local decontamination of invasive instruments has gradually been reduced to very low levels within hospitals although bench-top sterilisers remain in some small treatment centres and are used widely in dentistry. Most flexible endoscopes are processed within small local facilities typically adjacent to the endoscopy suite, although there is a current trend to create larger endoscopy reprocessing departments and to transport the endoscopes to the point of use in specially designed trolleys.

Decontamination facility requirements

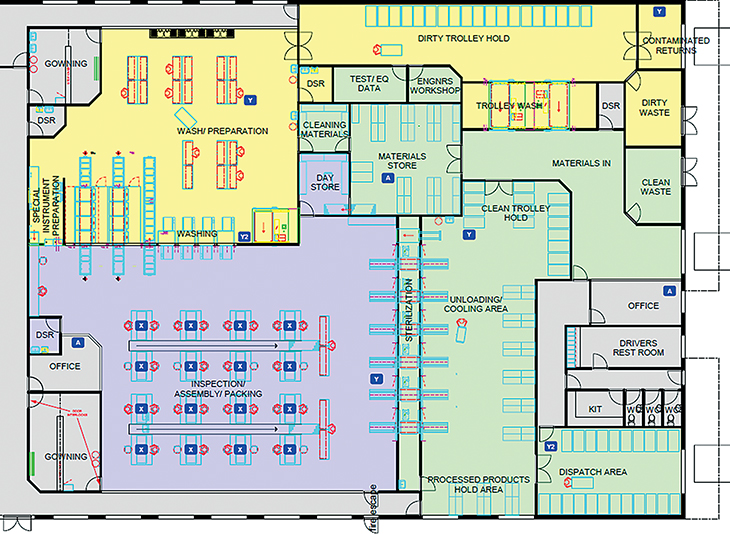

The Department of Health published a design guide to SSDs called Health Building Note (HBN) 13 (Department of Health 2004). The document sets out the rooms required, suggests a typical floor layout and offers advice as to the mechanical services (including ventilation) required. A typical sterile services production area layout is shown in Figure 6.1. The key features are:

- a work and staff flow that avoids cross-contamination with segregated clean and dirty work areas

- an ISO Class 8 (BS EN ISO 14644; International Standards Organisation 1999) controlled and monitored inspection, assembly and packing (IAP) room

- a dedicated wash room with pass-through washer–disinfectors that exit their load into the IAP room

- either double-door pass-through sterilisers or single-door sterilisers with a loading area separated from the IAP room and

- gowning rooms for both the wash and IAP rooms.

Whether medical devices are processed in a purpose-designed SSD or the smallest dental practice, a key objective for the facility must be the segregation of dirty from clean processes and a workflow through the room/facility that avoids crossover. Decontamination should never be undertaken within patient treatment areas.

Decontamination/Sterilisation Methods

The lifecycle approach

The decontamination life cycle (Figure 6.2) is a graphical means of representing each stage of the decontamination process. At all stages, the following issues need to be considered:

- management of processes

- location for decontamination activities

- activity at each location

- facilities and equipment at each location

- validation, testing and maintenance of equipment

- policies and procedures

- training.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree