History

An 83-year-old man had undergone implantation of a dual-chamber pacemaker 12 years previously for intermittent high-grade atrioventricular block. He did well for several years, but at age 79 experienced symptoms of congestive heart failure. During the initial hospitalization he was found to have significantly reduced left ventricular systolic function, with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 34%. On echocardiography he had global hypokinesis of the left ventricle. An initial pharmacologic stress study revealed equivocal changes in the inferior wall. Because of the equivocal changes a coronary angiogram was performed. No significant coronary artery disease was found, and the patient was classified as having idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The patient was started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, a beta blocker, a diuretic, and low-dose aspirin. He was already taking a lipid-lowering agent. He had resolution of his heart failure symptoms and was discharged after a 5-day hospital stay. Medications were titrated by his local physician over the following 3 months. The patient did well and returned to an active lifestyle and frequent international travel.

At 81 years of age he again began to experience symptoms, with mild dyspnea on exertion and rare episodes of orthopnea. Medications were altered, and the patient improved and managed as an outpatient. His LVEF was minimally changed, at 32%.

The patient returned 11 months later, at age 82, with profound heart failure symptoms. He was hospitalized again, and his LVEF by echocardiography was 26%. An ambulatory monitor reading was obtained, and the patient was noted to have frequent ventricular extrasystoles, representing 25% of ventricular beats during the 24-hour monitoring period.

The physician managing his care thought the opportunity for further optimization of his medical regimen was minimal. The patient was then referred for consideration of upgrade of his dual-chamber pacemaker to a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D).

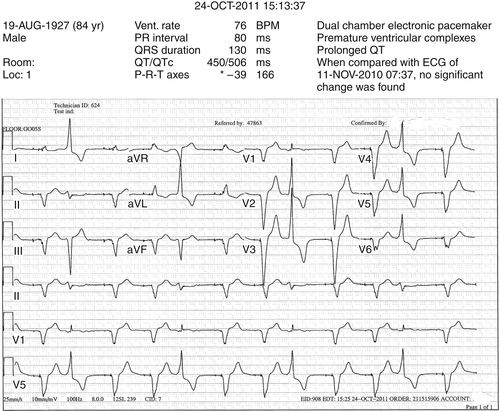

At the time of the initial referral evaluation, the patient’s medical regimen appeared optimal. The recent echocardiogram was reviewed and original measurements and observations confirmed. Pacemaker assessment demonstrated pacemaker dependency. He had frequent ventricular extrasystoles on 12-lead electrocardiogram, and frequent extrasystoles were also noted during auscultation. It was explained to the patient that the frequent ventricular extrasystoles could theoretically improve after a device upgrade, especially if improvement in left ventricular function was realized. If the extrasystoles did not improve, he was told that they might require treatment by pharmacologic suppression and/or an ablation procedure if the foci could be identified.

After a thorough discussion of the potential benefits and risks of CRT-D upgrade, the patient was upgraded to a CRT-D device. The chronic ventricular pacing lead was abandoned and capped. The chronic atrial lead was connected to the new CRT-D pulse generator, and a new right ventricular ICD lead and coronary sinus were placed. The defibrillation threshold was 14 J.

The postimplant chest radiograph is shown in Figure 40-1. Pacing and sensing thresholds checked at the time of discharge were excellent. For the period that the patient was monitored after implant, he continued to have significant ventricular ectopy. He occasionally had pairs and triplets but no longer salvos. The “PVC trigger response” was programmed “on” in an effort to maintain biventricular stimulation. The patient was discharged the day after the CRT-D upgrade and returned a few days later to his home for care to be continued by his cardiologist.

In the months immediately after the procedure the patient thought his peripheral edema was somewhat less noticeable but overall did not feel much improvement. He proceeded with an extended international trip that was intended to last for 5 months at a destination at a considerably higher altitude. Shortly after arrival he developed marked dyspnea on exertion to the point that he returned to his home. On return to the lower altitude his symptoms improved minimally.

His local cardiologist added spironolactone to his medical regimen, questioned possible dislodgement of the coronary sinus lead, and referred him for reevaluation of the CRT-D system.

He was reevaluated with chest radiography and echocardiography. On comparison of the postimplant and current radiographs, no significant change in lead positions was appreciated. Pacing and sensing thresholds were excellent. “True” biventricular pacing was noted to be 51%. A 12-lead ambulatory monitor was obtained. Forty percent of his ventricular beats were classified as fusion beats or ventricular extrasystoles. Of the beats classified as premature ventricular contractions, 80% were of the same morphology.

Given the high percentage of ventricular extrasystoles, low percentage of effective biventricular pacing, and, not surprisingly, lack of response to CRT, what options should be considered?

Current Medications

The patient was taking carvedilol 25 mg twice daily, furosemide 20 mg twice daily, lisinopril 20 mg daily, naproxen (Aleve) two tablets (250 mg) as needed, and enteric-coated aspirin 81 mg daily.