Communication with Young People

Adolescence defined by the WHO acknowledged the transitional nature of this life stage and the inherent variation between biological and emotional maturity and socio-cultural contexts (RCN 2008).

A hospital-wide consultation carried out in 2002 in a paediatric teaching hospital (Alder Hey 2002) involving 219 young people over the age of 12 years identified a number of areas that are pertinent to the preoperative adolescent patient:

- a dedicated area for adolescents

- pain relief when they needed it

- knowing what is said and written about them

- knowing the rules of the institution

- privacy and dignity to be maintained.

Christie and Viner (2005) discussed the specialised communication skills that are required when communicating with young people to ensure that the outcomes were agreeable to both parties, and outlined the following practical points for communicating and working with adolescents.

- See young people by themselves as well as with their parents. Do not exclude parents completely, but make it clear that the adolescent is the centre of the consultation. Do this routinely as a way of respecting their healthcare rights.

- Be empathic, respectful and non-judgemental, particularly when discussing behaviours such as substance misuse that may result in harm to the adolescent. Assure confidentiality in all clinical settings.

- Be yourself. Don’t try to be cool or hip – young people want a healthcare professional, not a friend.

- Try to communicate and explain concepts in a manner appropriate to their development. For young adolescents, use only ‘here and now’ concrete examples and avoid abstract concepts (‘if … then’) discussions.

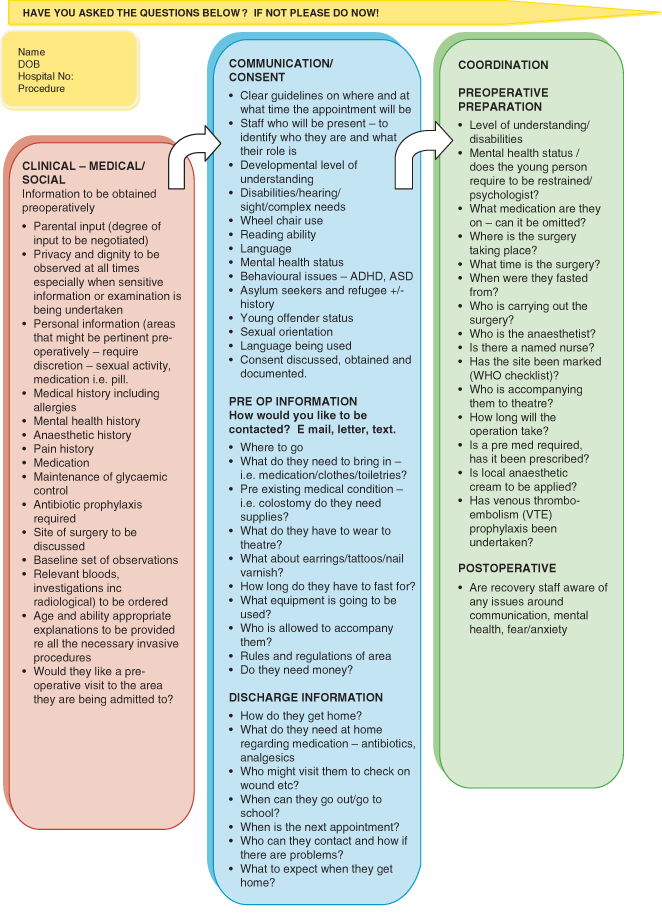

Figure 27.2A Perioperative adolescent checklist – 3 Cs. Adapted and modified from the World Health Organization.

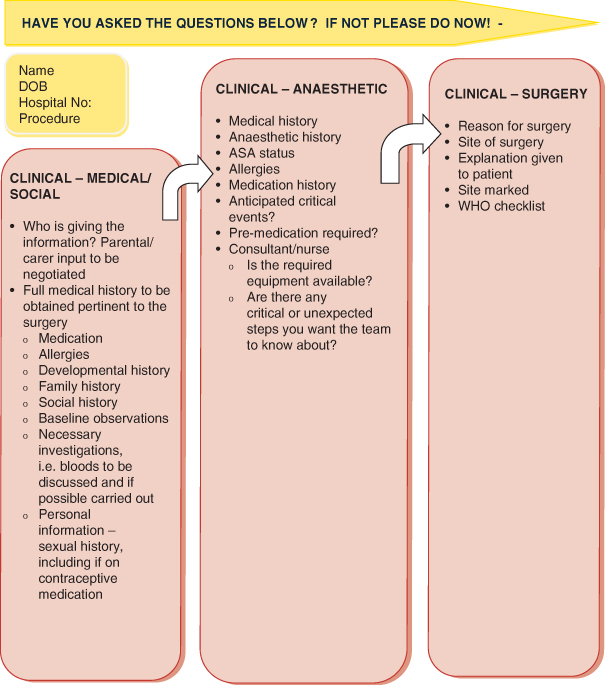

Figure 27.2B Perioperative adolescent checklist – clinical. Adapted and modified from the World Health Organization.

While these are general guidelines, modification will ensure that the concepts can be utilised in the theatre setting.

Communication and environment are two areas identified by a Department of Health document, You’re Welcome, published in 2011, which acknowledged the growing requirement that to meet the needs of young people services had to both communicate with them on what they required and also to act on the outcomes. ‘Doctors see the illness before they realise that I am actually a young person’ (WHO 2009).

The WHO ‘Safe Surgery’ initiative was undertaken to introduce a systematic way of organising theatres to address the issues around anaesthetic practices, surgical infection and poor communication (WHO 2008). This work is being adopted in many settings and is providing a framework that many are familiar with. Communication is seen as one of the vital areas. This should extend not only to the theatre environment itself but also to the perioperative care of the patient.

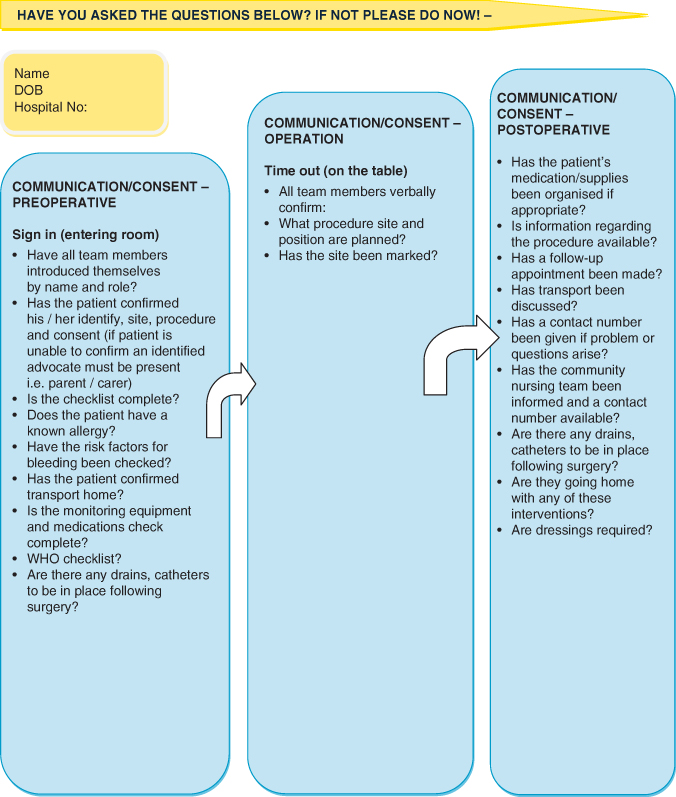

Figure 27.3 Perioperative adolescent checklist – communication/consent. Adapted and modified from the World Health Organization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree