These patients require close monitoring in the post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU) as they can collapse due to reperfusion injury following reduction of the intussusception.

Foreign body in the airway

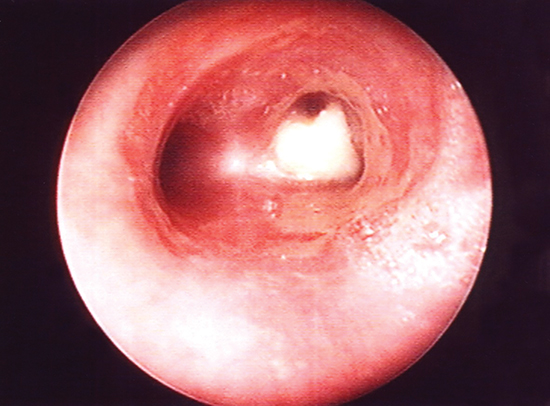

Small children are prone to put things in their mouth and sometimes they either swallow them or occasionally inhale them. Toys have warning messages on them to inform parents and carers of the appropriate age the toy is intended for, and those toys with small removable parts are recommended for children over three years of age. Food does not generally carry the same warning messages and infants can choke on small hard items such as pieces of carrot or nuts. Peanuts are particularly irritant if lodged in the airway and should not be left long even if the child appears to not be distressed. The anatomy of the airway is such that the right main bronchus is slightly larger and at less of an angle to the trachea than the left, therefore a peanut would be most likely to pass through the trachea and become lodged in the right main bronchus as shown in Figure 26.2.

Removal of the peanut involves the infant undergoing an emergency bronchoscopy under general anaesthetic. Some surgeons will initially insert a flexible bronchoscope either through an ET tube or through a laryngeal mask to ascertain the presence of a foreign body. In order to remove the peanut a rigid bronchoscope and optical forceps are required. The rigid bronchoscope is inserted into the airway with the aid of a laryngoscope following the spraying of local anaesthetic to the vocal chords. The quality of vision through a rigid bronchoscope far exceeds that of the flexible bronchoscope, making visualisation much better. The child can be ventilated through the bronchoscope once the side-vents on the scope have passed through the chords and cricoid cartilage. The optical forceps are then passed down the bronchoscope and the peanut grasped, removing the whole scope, optical forceps and the peanut from the child in one movement. Airway control is then passed back to the anaesthetist. The bronchoscope is then reinserted to ensure no fragments remain. Due to the vocal chord’s being sprayed with local anaesthetic the child cannot eat or drink until the effect has worn off, usually a couple of hours.

Figure 26.2 Peanut in right main bronchus. Photo courtesy of David Crabbe, Consultant Paediatric Surgeon.

Advances in Paediatric Surgery

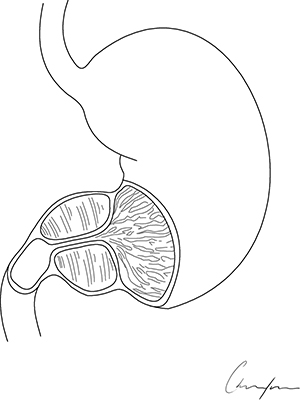

Surgery has advanced over the years and paediatric surgery is no exception. Breakthroughs in technology and scientific research have changed the way we manage surgical procedures. For example, for pyloric stenosis, a condition where the pyloric sphincter, the outlet of the stomach, is hypertrophied (Figure 26.3), the surgical approach has changed dramatically. Surgery involves splitting the pyloric sphincter muscle from the stomach to the duodenum, leaving the mucosa intact. Pyloric stenosis has a strong familial pattern of inheritance and as such different generations of the same family may have undergone essentially the same procedure, but through a different approach. In the past, most babies with pyloric stenosis underwent a Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy through a right upper transverse incision (see incision A Figure 26.4) but more recently surgeons perform the pyloromyotomy through a cosmetically appealing supra-umbilical incision (see incision B Figure 26.4). Many centres are now adopting a laparoscopic approach to this surgery, using delicate 3 mm laparoscopic instrumentation. With the laparoscopic approach the incisions (see incisions C Figure 26.4) are so small that in a year’s time it is difficult to even see the scars.

With increased use of laparoscopic surgery in paediatrics, reducing the need for large disfiguring incisions, many procedures are now carried out with much improved cosmetic results. For many years there has been evidence that laparoscopic surgery can decrease the likelihood of adhesion formation as shown by Lundorf et al. (1991). Advances in technology have aided the development of robotic laparoscopic surgery, commenced in adult surgery and found to be enormously useful for prostatectomy among other procedures. In recent years, as robotic equipment (ports and instrumentation) has become smaller this surgery has been introduced into paediatric practice and is suitable for many varied procedures (Najmaldin and Antao 2007). It has the benefits of increased magnification, three-dimensional vision and greater, more precise movement of the instrumentation than conventional laparoscopic surgery. It is particularly useful for those laparoscopic procedures where a large amount of suturing is required (e.g. pyeloplasty). Laparoscopic suturing is extremely time-consuming and the use of the robot can make this much quicker. A robotic surgical procedure on a child is shown underway in Figure 26.5.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree