Oesophageal Atresia

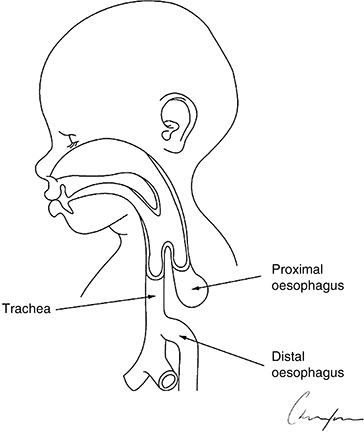

The most common configuration of this condition is oesophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula (85%) as shown in Figure 25.2. If not identified on ultrasound examinations during pregnancy the baby presents with excessive salivation, choking, coughing and respiratory distress or problems if passing of a nasogastric tube is attempted. Many of these neonates will also have other associated congenital abnormalities. This congenital condition requires surgery to close the fistula, thus preventing over gastric dilatation as the baby breathes, which can lead to gastric perforation, and anastomosis of the two ends of the oesophagus to effect continuity to allow oral feeding and prevent aspiration. After birth a Replogle tube is inserted into the upper pouch of the oesophagus via the nasal route. This tube has two lumens, one inside the other, to allow small quantities of saline to be inserted via the outer tube to soften salivary secretions and suction to be applied to the shorter inner tube to prevent overflow of secretions into the lungs without getting blocked by sucking against the mucosa of the upper pouch. If the neonate requires artificial ventilation this should be performed with low pressures to lower the risk of gastric perforation and surgery becomes more urgent.

Figure 25.2 Baby born with oesophageal atresia and distal tracheoesophageal fistula. Image courtesy of David Crabbe, Consultant Paediatric Surgeon.

The procedure is usually carried out through a right thoracotomy unless the neonate has an abnormally positioned aortic arch. It is possible to block the fistula using a small Fogarty embolectomy catheter inserted through the fistula with use of a rigid bronchoscope. This is of temporary benefit while performing the thoracotomy. In the very unstable neonate it may be necessary to perform a crash thoracotomy and just ligate the fistula, bringing the baby back to theatre a few days later to formally close the fistula and anastomose the oesophagus.

Some neonates with this congenital deformity will require multiple trips back to theatre to deal with further complications, such as the gap between the two ends of the oesophagus being too far apart to anastomose, requiring either gastric transposition or interposition of colon or small bowel to the gap. They can go on to develop tracheomalacia, oesophageal strictures at the anastomosis site, food blockages in the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux requiring surgery.

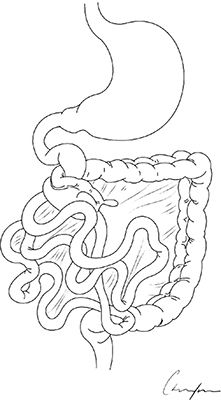

Malrotation with volvulus

Malrotation of the gut is a congenital deformity where the distance between the duodenojejunal flexure (DJ flexure) and the caecum is small, leaving the mid-gut mesentery on a narrow pedicle. The DJ flexure should sit to the left of the spine in line with the pylorus of the stomach and the caecum should sit down in the right ileac fossa. In this normal configuration the mid-gut mesenteric base is wide and extremely unlikely to twist. If the caecum is high and the DJ flexure to the right of the spine the mid-gut can twist, termed a volvulus (Figure 25.3), which cuts off the blood supply to much of the small bowel. This is a real surgical emergency and, if not treated expeditiously, can lead to much of the bowel needing to be removed and a life of living with short bowel syndrome for the baby with complications of parenteral nutrition, malabsorption issues, bowel lengthening procedures and liver and small bowel transplant prospects for the future if the baby survives the initial period.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree