Question 1

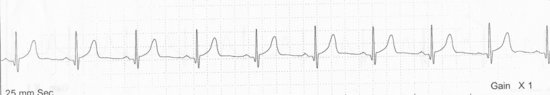

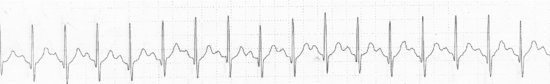

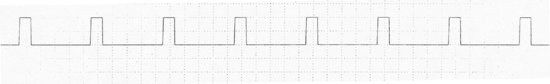

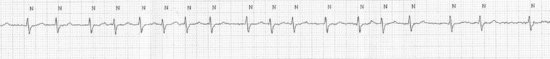

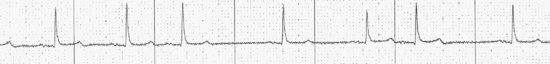

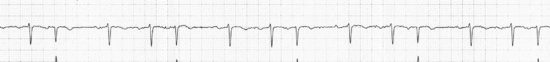

You are walking past the nurse’s station on a medical unit because there is a bathroom down the hall you want to use. All at once, a nurse tells you to look at the cardiac monitor and asks if she can remove the telemetry unit from the patient. The rhythm looks like this:

You reply:

Answer to Question 1

Well, what is the rhythm? You review the relevant features: regular, slower than 100, faster than 60, a P wave before each QRS with the proper PR interval … hmmm … looks like sinus … yes, this looks normal! And the call (see page 3) is just what we expect to hear. You are right, this is normal sinus rhythm. So what is the correct answer? Answer 4 of course; never give advice on a patient you don’t know anything about! Who knows, the patient might have just had an 11-second pause and the staff decided they didn’t want to do CPR again.

Question 2a

The setting is the nurse’s station again, this time on a surgical floor, and the nurse asks you to look at a rhythm strip. “I think it’s sinus rhythm,” he says. “What do you think?” So what do you think?

Answer to Question 2a

The answer is 5, just as if you are in the forest trying to figure out what kind of a bird you are looking at. The setting is very important: you will see one kind of bird on the seashore and other kinds in a pine forest. In medicine the setting is part of the history, and just as with birds you can expect certain arrhythmias in patients with lung disease and other types in heart failure patients. And if you can’t figure out what you are looking at, ask for more strips or a 12-lead ECG! At the least it will buy you time till someone smarter comes along, but often the answer will become apparent and then you will get the credit! … Now continue to Question 2b …

Question 2b

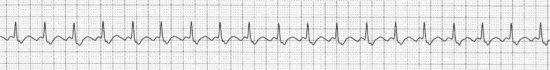

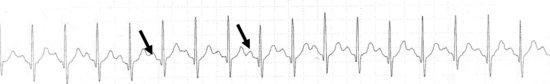

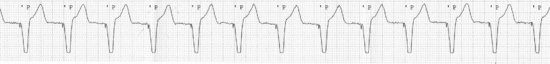

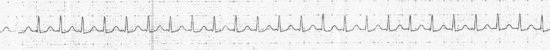

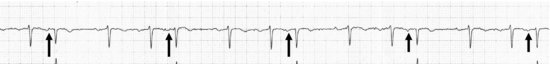

Anyway, the nurse tells you the patient is two days post-op following a hip replacement and that he has chronic lung disease. [Ah … lung disease, you say to yourself … supraventricular arrhythmias … ] And then he brings you another strip:

So now you say:

Answer to Question 2b

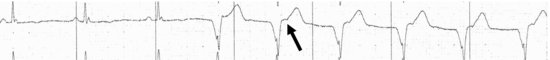

If you are pigheaded, you will ignore the evidence of your own two eyes and say answer 2 (which is wrong), because while before you really couldn’t see clear P waves of any kind, now you can clearly see the sawtooth flutter waves of atrial flutter (see arrows), where there are periods of 3:1 instead of 2:1 AV conduction:

This arrhythmia is not unusual in patients with lung disease. You don’t need a saw (5 is wrong unless you need to saw off a cast, this is an orthopedic patient) but in case you forgot what sawteeth look like there is a photograph on page 25. You don’t need more rhythm strips, you have all you need right now (answer 3 is wrong as well). A cup of coffee wouldn’t hurt, but answer 1 is the best answer.

Question 3

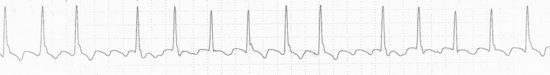

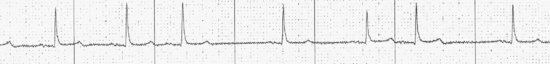

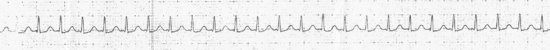

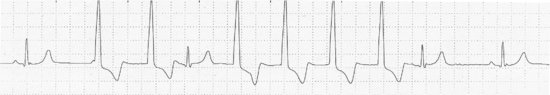

So you proudly get up to leave the nurse’s station after correctly diagnosing the last rhythm. As you do so you accidentally knock over the cup of coffee one of the techs brought you, spilling it down your leg. The warning on the coffee cup lid correctly advises that the contents are hot, and you shout with agreement. The tech rapidly applies telemetry electrodes to your chest as you are lowered to the floor, while others use bandage scissors to cut away your lower pant leg where the coffee spilled. You are handed the rhythm strip as the Trauma Team arrives:

You say:

Answer to Question 3

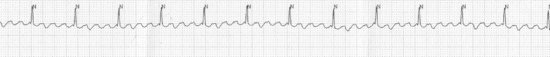

Interestingly, the heart rate is faster than in Question 2, but in contrast to that rhythm strip, P waves are clearly visible here (see arrows):

The setting is unmistakably one of catecholamine excess, and even if you couldn’t reach your Field Guide you should have no trouble identifying sinus tachycardia, with answer 3 the best answer. By the way, diltiazem won’t slow a sinus tachycardia very much anyway (answer 1 isn’t a good choice). Don’t worry about your doughnut, and although it’s always a good idea to call your mother, now may not be the best time.

Question 4a

You are with your physical diagnosis group listening to heart sounds in the CCU. It’s really scary there, with all sorts of wires and monitors, the patients sick, and the nurses intimidating. There is a commotion at the bedside, and your first thought is that you did something wrong. Your preceptor takes a strip from the most frightening nurse of all, hands it to you, and asks, “What would you do here?”

You:

Answer to Question 4a

Of course you look at the strip (answer 4); you may then elect to hand it back. An important lesson learned here, however, is that you must look at the rhythm strip before you make any comments or decisions; only the Section Chief may render a diagnosis without reviewing any data … Now continue to Question 4b …

Question 4b

Once you do take the strip you really are obliged to identify the rhythm and say something intelligent to the preceptor. While stalling for time you ask:

Answer to Question 4b

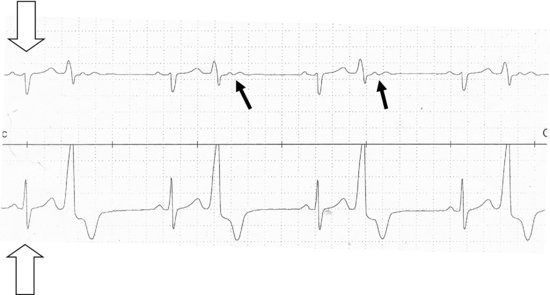

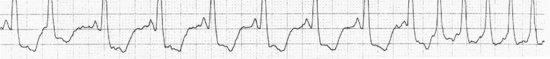

So what are we looking at? You can see that this monitor looks at two leads at once; this is often very helpful in figuring out arrhythmias. There are lots of premature beats here; in fact, every other beat is premature. You can identify the normal beats (open arrows) because they have nice P waves in front of them at the proper interval: they are sinus beats.

The early beats are wide, without preceding P waves, and are therefore premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). The fact that every other beat is a PVC indicates a pattern of bigeminy (not to be confused with the mild expletive, “by jiminy!”). For extra credit, every third beat as a PVC is trigeminy and every fourth beat as a PVC is quadrageminy. Nobody cares about every fifth beat or higher.

Now remember how we indicated on page 33 that if you can show P waves marching independently of the extrasystoles you have proven Beyond Any Doubt Whatsoever that the beats are absolutely positively ventricular in origin? Grab your magnifying glass and calipers, dear reader, because those little marching P waves which are not affected by the PVCs can be seen with just a little imagination (solid arrows). You won’t see this again for at least five years.

You already seem to know an important strategy for rounds: answering a question with another question. Now that you have identified the arrhythmia you can answer the preceptor. You did buy time, but if you ask the right questions you sound smart, and here the extra information might actually be helpful. As we mentioned earlier, the habitat of the arrhythmia can help us decide if the rhythm is dangerous or not. In the CCU PVCs bother us, but if the ejection fraction is low (say under 35%) we get nervous because of a higher risk of potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias. An elevated troponin indicative of an acute coronary syndrome would have us worried even more, and a low potassium (under 3.5) would bother us too: each of these things might suggest a risk of the PVCs leading to a more dangerous ventricular arrhythmia. So answer 6 is correct. We generally will not treat these PVCs with an antiarrhythmic (so answer 5 is wrong) and it usually doesn’t matter what time it is unless it is close to sign-out time. Oh, and one other word of advice: in the CCU don’t even joke about a cardiac catheterization because an interventionalist might be listening.

Question 5

We’ll keep this simple. You are reading ECGs with me. It is 8 AM and you haven’t had any coffee yet (actually, after Question 3 you drink only orange juice). I look at an ECG and flip it in your direction and ask you, “What’s the rhythm?”

You reply:

Answer to Question 5

Now this one you might have to think about a bit (so answers 1 and 3 are wrong) Your first thought should be that the rhythm is NOT regular. Atrial fibrillation? Wait! There is a P wave in front of every beat, so atrial fibrillation (answer 2) is out. Premature atrial complexes? Then the underlying rhythm should be regular with a clearly premature beat (preceded by a P wave) and that’s not there either (answer 4 is wrong). It looks like it gently speeds up and slows down. So that leaves the very benign sinus arrhythmia (answer 5), speeding up and slowing down usually in synch with breathing.

This ECG was from a healthy 44-year-old in for a routine physical. Should we treat it with anything? Remember its “Care and Feeding” section (page 8): treat it with love and affection!

Question 6

The below was seen on the monitor of a patient just brought up from the Emergency Department:

You should:

Answer to Question 6

We’ll get straight to the point: there is nothing in nature that generates square waves like this. So this cannot be a natural rhythm. Even the Tin Man had a normal QRS preceded by a P wave following his heart transplant.1 So this has to be electrical artifact of some sort. This is a recording of the calibration pulses from the telemetry unit; answer 4 is the correct answer. Answer 3 isn’t a bad idea; we’ll give part credit for the good intention. Answers 1 and 2 are wrong. Remember: always check the patient before you do something drastic!

Question 7

You are sitting by the monitor in the CCU when there is a commotion and you are shoved out of the way. Nursing staff are looking at strips coming from the patient in Bed 4 who came in earlier today with a myocardial infarction and had an angioplasty with placement of a stent. The patient is reading a newspaper, but half of the staff want to shock her and the other half want to start amiodarone. Tempers are getting short, but one nurse hands you the below strip and asks you what they should do.

You say:

Answer to Question 7

Well, first you will almost never want to shock anyone who is reading a newspaper and who otherwise looks okay, so answer 2 is out. Thinking about a pacemaker is a good idea since the complexes are wide and pretty slow, but I don’t see a pacemaker spike anywhere … and it is hard to put one in without anyone noticing. So answer 3 is out as well. Knowing the ejection fraction is usually a good thing, but you have to make a therapeutic decision right away, and the ejection fraction doesn’t enter into our decision-making here. The key is to identify the rhythm. It starts out sinus but then this relatively slow wide complex rhythm appears without P waves in front of the beats. A wide complex rhythm with no preceding P waves is generally ventricular. Oh no, ventricular tachycardia?? No, calm down, the rate starts off around 75, so this is an accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) which is a benign, self-terminating rhythm. So answer 1 is correct. Answer 5 is incorrect, we don’t treat this rhythm, and anyway, never order anything you can’t pronounce.

By the way, if you have really good eyes you can see starting with the second beat of the AIVR retrograde P waves (see arrow) following the QRS complexes; these represent the atria being activated by the electrical impulse that originated in the ventricles spreading backwards to the atria through the atrioventricular (AV) node.

If you can convince others that you can see these you are in line to become Divisional Chief. Or, better yet, Ruler of the Queen’s Navy.2

Question 8a

All right, we’ll make this one simple. What’s the rhythm?

Answer to Question 8a

So let’s go through our identification process. Regular or irregular? The QRS complexes look irregular to me; if you’re not sure, use your calipers, paper clip, or index card with little ink marks to satisfy yourself. It is irregular. Next question: are there P waves? The baseline is just a wiggly squiggle between the QRS complexes; I don’t see any clear P waves. You might see one little bump in front of one QRS that might tempt you to call it a P wave, but if you look in front of all the other QRS complexes a similar bump just isn’t there. No P waves, so multifocal atrial tachycardia (answer 2) is out.

It isn’t regular and there are no P waves, so no way it’s sinus rhythm, nervous or not (answer 1 is wrong). I see no sawteeth, so answer 4 “forget about it.” This is atrial fibrillation (answer 3 is correct) … Now continue to Question 8b …

Question 8b

Before you finish patting yourself on your back I have one more little question for you: how fast is it going?

Answer to Question 8b

Ah, that’s not so easy, right, because it’s irregular – each R–R interval is different! You could measure each R–R interval, average them, and then convert that to beats per minute. That’s what our electrophysiologists do, which is one reason their procedures take so long. You can cheat and look at the monitor readout, but sometimes they’re wrong and anyway I cropped the part of the strip which showed the heart rate so you can’t use that here. A clever way to get an average heart rate during any irregular rhythm is to count the number of beats in a 6-second interval and then multiply by 10 (which gives you the number of beats in a 60-second interval [that’s beats per minute, Einstein!]). To mark off a 6-second interval you can either count off 30 big boxes (30 × 0.2 seconds = 6 seconds) or better yet, take advantage of the 3-second tick marks placed on most rhythm strips by the ECG industry for your personal convenience (see arrows).

Pretty neat, eh? The rate is around 80 beats per minute (answer 2), which is pretty well controlled.

Question 9

You are on an orthopedics rotation and are making rounds. The nurse hands the surgeon a copy of the post-operative ECG. He says “Wazzat?” and flips it to you as he walks on, checking casts and dressings. The nurse wonders if the rhythm is really sinus, as the computerized interpretation says it is.

You say:

Answer to Question 9

Even if you aspire to replacing joints you should be able to recognize this as an ECG tracing, so answer 4 is wrong. The rhythm is regular, so it could be sinus, but wait … where are the P waves? There isn’t a clear P in front of every QRS, instead there are sawteeth between each QRS. So it isn’t sinus rhythm. (Answer 1 is wrong; believe me, the computer is often wrong!)

All right, these aren’t the sharpest sawteeth you ever saw, they look like your saw might look if you tried to use it to cut a brick, but they are sawteeth just the same. This is atrial flutter (answer 2). I see three flutter waves between the QRS complexes, with a fourth under the QRS. That makes four flutter waves for every QRS, hence 4:1 block. The rate is around 80, which is about right for 4:1 block (flutter waves are usually around 300 per minute, 300/4 = 75 … well, that’s roughly 80, right?). Why isn’t this atrial fibrillation? Well, for one thing, it’s perfectly regular (atrial fibrillation is almost always irregular), and the flutter waves are quite uniform across the strip while the baseline in atrial fibrillation is a constantly changing squiggle.

Question 10

This 45-year-old woman was at a great party last night, and consumed an unknown amount of alcohol. She came to the Emergency Department the next morning because she felt her heart fluttering long after her boyfriend left. She normally takes no medications.

This is:

Answer to Question 10

First of all, if she admits to three drinks, the standard conversion factor is two: she probably really had six drinks. Alcohol can trigger arrhythmias, and arrhythmias after a weekend of debauchery have been happily dubbed the “Holiday Heart Syndrome,” less than happily for those of us who have to work on Monday to pick up the pieces.

So it’s irregular. Any P waves? There are some little bumps in front of some QRS complexes, but when you look in front of other QRS complexes those bumps aren’t really there. Irregular with no P waves can mean only one thing: atrial fibrillation (answer 5 is correct). Supraventricular tachycardia is perfectly regular and fast (usually over 150) without discrete P waves, so answer 2 is out. No sawtooth flutter waves (see Question 8), so answer 4 is wrong. There are no sinus beats (no P waves) so answer 3 is wrong. Answer 1 is probably correct anyway, but answer 5 is a better answer.

How fast is the rhythm? Count the beats in a 6-second segment and multiply by 10. I get around 125 beats per minute, which is a little rapid for my taste. Check out the “Care and Feeding” section for atrial fibrillation (pages 23–24); if the blood pressure was OK I would slow this down a bit with a “slower-downer” like a β-blocker, diltiazem, or verapamil.

Question 11

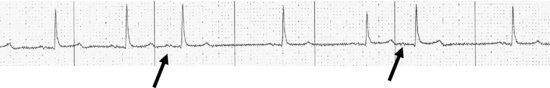

While you are drawing a blood sample from a patient who came to the Emergency Department with a sore throat, a nurse runs in with a defibrillator and demands you step aside so he can shock him. You do a double-take, and your patient is looking as surprised as you are. Here is the monitor strip; what is it and what should you do?

Answer to Question 11

First, as always, look at the patient. Since he’s wide awake, looks good, and is talking to you, he will almost never need to be shocked, so put the paddles away. Now let’s look at the rhythm: regular but no P waves, and the complexes are wide. How fast? Looks like about 80 beats per minute.

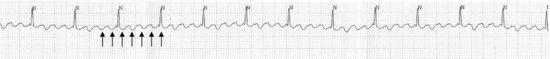

So answer 2 is wrong, it’s not ventricular tachycardia. It could be accelerated idioventricular rhythm, but wait! What are those little spikes in front of each QRS (see arrows)? Those are pacemaker spikes! If you didn’t notice them you would be hissed out of the Emergency Department, so check for them carefully in each lead; they are often small and easy to miss. Answer 1 is correct, and answer 3 is wrong although it was a good thought (see page 36 to remember what to do!). The pacer spikes rule out answers 3, 4, and 5. It can’t be sinus rhythm since there are no P waves; where did you hear about answer 5, anyway?

Question 12a

This person complains of palpitations. What are they?

Answer to Question 12a

Well, is there an underlying rhythm? Yes, and it does look regular, with an early (premature) beat every third beat.

We see P waves in front of every regular beat, and come to think of it, there are small but unmistakable P waves in front of the premature beats also (see arrows). So the underlying rhythm is sinus (answer 3 is wrong), and we see no pacemaker spikes, so answer 2 is wrong also. Premature beats which have the same shape as normal beats and are preceded by P waves are PACs (answer 4 is correct). They are not PVCs (answer 1 is wrong) … Now continue to Question 12b …

Question 12b

What might cause them?

Answer to Question 12b

Answer 7 is correct; if we see PACs we might think of (and check for) lots of things, but in many people they might just be there for no good reason except to torment arrhythmia students.

Question 13a

This person walked into a Midtown Manhattan restaurant and ordered an appetizer, an entrée, dessert, and a double espresso without looking at the prices. He received the check, became lightheaded, and called for an ambulance. The paramedics apply a monitor. You are dining at the next table, lean over, and peek at the rhythm:

It is:

Answer to Question 13a

As far as answer 1 goes, you are a student of arrhythmia armed with your calipers (or index card or paper clip) and magnifying glass, so it is your business; answer 1 is wrong.

It is disgustingly regular, so answer 2 is out. There are no P waves that even I can see, so that argues against sinus tachycardia. And by the way, how fast is it going? If you are counting boxes you can estimate somewhere between 150 and 300, and if you use the 6-second trick (oops, no tick marks here, you will have to count 30 large boxes (30 × 0.2 seconds = 6 seconds [which is 15 cm, if you have a ruler!]) it works out to about 190 beats per minute. Wow, that’s fast! No wonder he’s dizzy! This is really too fast for a sinus tachycardia, and without P waves I think that rules out answer 5. Atrial flutter with 2:1 block is usually around 150 or so, and there is no hint of sawteeth, so answer 4 is unlikely. That leaves SVT as the best answer (answer 3) … Now continue to Question 13b …

Question 13b

The paramedic interprets your covert glance as a sign of knowledge, and asks you what to do with the patient?

You say:

Answer to Question 13b

I have never seen the diving reflex work, and I seriously expect it would lead to a fight, so I would avoid answer 2. Answer 3 might actually work, and would be worth a try, especially in a younger individual who had little risk of carotid disease. Answer 4 is almost always effective and is probably the best choice. Answer 1 should go without saying.

Now if you were impertinent, you could argue that atrial flutter is a form of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), and that the choices for answers weren’t good ones. For that I would tell you that when I say SVT, I mean a specific kind of tachycardia that isn’t atrial flutter or fibrillation, and I would give you a reference to look up and review for us on rounds tomorrow.3 That would show you!

Question 14

This patient complains of palpitations also. It seems everyone is complaining about palpitations!

What are those early beats?

Answer to Question 14

The wide complex beats are clearly early, and are bizarre-looking with no preceding P wave. That makes them PVCs (answer 4). There are no pacemaker spikes (answer 1 is wrong), the quality of the strip looks pretty good (so it’s not artifact; 3 is wrong), and if they had preceding P waves and looked like the sinus beats they would be PACs, but they don’t, they don’t, and they aren’t; answer 2 is wrong as well. They are really just plain ol’ PVCs.

Check the potassium.

Question 15

This is from a 68-year-old man with bad lung disease. He does NOT complain of palpitations!

What is the rhythm?

Answer to Question 15

The Cha-cha is a dance, so answer 3 is wrong although the rhythm is suggestive. There are irregular beats but there are P waves in front of each one (see arrows), so it’s not atrial fibrillation; answer 1 is wrong. Answer 4 is correct: this is sinus rhythm with PACs. Multifocal atrial tachycardia is much faster with at least three different P wave morphologies, so answer 2 is incorrect.

In general, PACs and supraventricular arrhythmias are common in patients with lung disease – but not everyone feels them!

Question 16

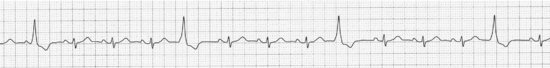

On morning rounds in the coronary unit the resident looks at a rhythm strip from a 72-year-old woman with a past history of a myocardial infarction, who was admitted with chest pain. She says, “Oh, my God, check the potassium, magnesium, and porcelain, start lidocaine, and call the electrophysiologist, STAT!!” Everyone runs off in different directions, and the rhythm strip flutters to the ground. You pick it up, dust it off, and look at it.

You then take a deep breath and say:

Answer to Question 16

You should know that if someone makes reference to a serum porcelain level (there’s no such thing) they are implying the requestor is extremely obsessive. So answer 1 is just to imply the resident is a little wacky, but is definitely not the right answer! First you should glance at the patient, and since he is watching television and looks fine, you should resist the temptation to grab the defibrillator, let alone turn it on! But, before you totally scrap answer 2, what actually is the rhythm?

I see sinus beats at the beginning and end of the strip, with a run of wide complex beats without P waves in the middle, at around 90, with a couple more earlier in the strip. And it looks like the first beat is actually competing with the sinus P wave (see arrow). This is accelerated idioventricular rhythm, (answer 3), a benign rhythm which may be scary to watch, but which is stable (just look at the patient!) and does not require any therapy. The beats are wide without preceding P waves so it’s ventricular – but the rate is under 100, so it’s not ventricular tachycardia. So no defibrillator: answer 2 is out. No pacer spikes mean it’s not a paced rhythm (unless your eyes are bad or you were in a rush and missed them). If you mumbled answer 4 as you were musing I wouldn’t yell at you, but after perusing the strip and reflecting carefully you should realize it is incorrect. If you said answer 5 the resident would assign you to fecal analysis for the next week, but folks don’t use lidocaine much anymore.4 If it was ventricular tachycardia (but it’s not!) you could use lidocaine if you really wanted to, but nobody remembers how to dose it …

Question 17

Last night you were on call, and the nurse called about a patient in the ICU on a ventilator who “had runs of ventricular tachycardia.” In your sleep-deprived state you managed to find out the patient’s recent echocardiogram was “OK,” the potassium was “good,” and the patient was on no meds that could trigger arrhythmias. So you managed to order intravenous amiodarone since you figured that would calm down the rhythm. It worked, but you checked out last night’s rhythms before morning rounds:

You decide:

Answer to Question 17

Now I’ll admit this one might be a little bit tricky, but we’ll use the Field Guide and all of our deductive skills to get it right. A cup of coffee (answer 2) isn’t a bad idea, just remember it’s hot. Who needs the resident (answer 4) anyway? So look at the run:

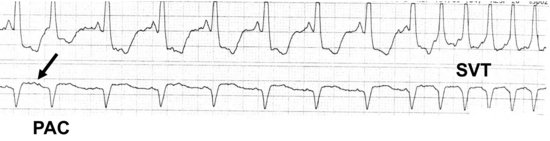

The complexes are wide, but wait! The normal complexes are wide too! And don’t those rapid complexes look identical to the beats which are clearly sinus? For those doubting Thomases amongst you, I have provided a strip showing two leads (frequently available on many monitors) which show the rapid beats indeed look identical to the sinus beats in both leads. And there is a premature atrial complex (PAC) at the beginning of the strip. So put it together: ventilator (lung disease), known PACs, and runs of beats which look just like the sinus beats at around 190, although I’ll admit I can’t see clear P waves either. This had got to be a run of SVT; answer 3 is right. Since amiodarone works for all sorts of arrhythmias you don’t have to actually admit to anyone you were wrong, but I would suggest you quietly switch it to a safer medication that would work just as well for SVTs.

Question 18

This strip came from a 76-year-old man who had a monitor attached because he was having dizzy spells. He recently had verapamil (a calcium channel blocker) added to his metoprolol (a β-blocker) for high blood pressure.

You think:

Answer to Question 18

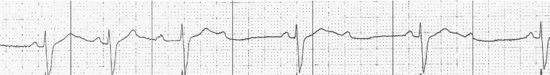

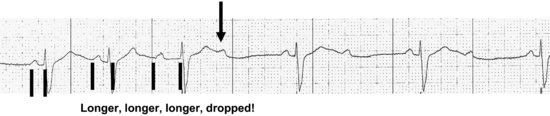

All right, I didn’t know that rhyme either until recently (see the introduction to medical poetry on page 17), but I told you it would be on the test! Look at how the PR gets longer and longer (tick marks) until … that’s right, there’s a P but no following QRS (see arrow)!

The next P is conducted normally, but the one after that is blocked again. So this is Mobitz I second degree atrioventricular (AV) block, also called Wenchebach by those of us on a first name basis (all right, second name basis) with these arrhythmias. Answer 1 is correct. Johann Christian Bach (answer 2) sounds close, but is wrong, although he was a darn good composer! This is not sinus arrhythmia; if you used your calipers you would see the sinus P waves are perfectly regular. And don’t give more verapamil! The combination of a β-blocker and calcium channel blocker can be more than the poor AV node can handle, and is the cause of this conduction problem; more verapamil would likely lead to complete heart block. How do we care for this rhythm? Stop the offending drugs!

Question 19

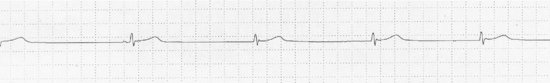

Here’s a rhythm from last night. It’s 1 AM in the morning and I got a panicked call from the telemetry nurse who tells me there is a patient on a monitor who has a heart rate of 35. I ask him what the patient complaining about, and the nurse answers that the patient isn’t complaining about anything, he is asleep. Recognizing that without direction this kind of conversation can go on for hours, I cut to the chase and ask him to fax me the rhythm strip and tell me what the patient’s vital signs are, what his meds are, and why he is in the hospital. The patient, the nurse tells me, is 45 years old, just had some sort of podiatric surgery, is on no cardiac medications, has a blood pressure of 125/65, and now is annoyed about being woken up. The nurse appears to be angling for a pacemaker or at least some atropine. You look at the strip:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree