While considering the patient’s individual risk of thrombosis it is important to also consider the patient’s individual risk of bleeding:

- active bleeding

- acquired bleeding disorder

- concurrent use of anticoagulants

- lumbar puncture/spinal anaesthesia within 4 hours

- lumbar puncture/spinal anaesthesia planned in the next 12 hours

- acute stroke

- low platelet level (<75 × 109/L)

- uncontrolled hypertension (230/120 mmHg or higher

- inherited bleeding disorders – haemophilia/von Willebrand’s disease.

How to Assess a Patient’s Risk of Venous Thromboembolism

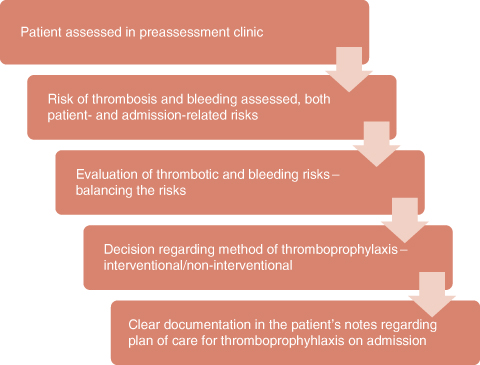

Risk assessment is the first step in VTE prevention and is used to accurately identify those patients at risk of developing a VTE.

Each patient has individual risk factors for thrombosis and bleeding (as listed above) and these need to be assessed carefully.

All hospitals now have a risk assessment form based on the Department of Health form which should be completed, dated and signed within 24 hours. This is to comply with the CQUINS target, but is essential for the wellbeing of the patient, regardless of targets.

When the risk factors are related to an individual patient, one can understand why some patients are more ‘at risk’ than others. For example, an elderly patient undergoing a hip replacement who has had a previous VTE event is at a higher risk of VTE than a young patient having day-case surgery, with no previous history of VTE (young, no perceived immobility, no major vessel damage and no expected dehydration or thrombophilia).

It is at preassessment that the patient is fully informed of the impending surgery and the associated risks. At this time the patient should be given documentation to take home and read about preventing VTE.

Methods of Thromboprophylaxis

Once an assessment of the thrombosis and bleeding risk is made, a decision for type of thromboprophylaxis is required. This decision may also be influenced by the reason for the hospital admission, and these risks are identified on the assessment form as ‘admission-related’ risks; for example, a patient may have a high risk of thrombosis due to a previous event, have a thrombophilia and family history of thrombosis, (thus carrying a high risk of VTE) but the procedure for which they have been admitted carries a high risk of bleeding (neurosurgery) and this may alter the decision on the type of thromboprophylaxis.

All patients, regardless of their risk of thrombosis or bleeding, require some form of non-interventional thromboprophylaxis, often just referred to as ‘reducing the risk of VTE’ or ‘general advice to patients’ and ‘best practice’. In the author’s opinion, this method of thromboprophylaxis is often undervalued and underused, probably as it is almost impossible to evaluate, but it is essential for all patients. It involves:

- Patient education: Many patients will not be aware of the words ‘deep vein thrombosis’ or ‘pulmonary embolism’ but have heard of blood clots, so it is important to ascertain the patients understanding of the condition prior to further discussion. All patients should be informed of their individual risk and how they can reduce the risk.

- Early mobilisation: All patients should be encouraged to move as soon as is practically possible and it is very important that all healthcare professionals are proactive in encouraging this. Ideally the level of mobility achieved each day should be documented and increased immobility addressed. Those patients who are immobile should be taught simple leg exercises and, if they are unable to perform these, the healthcare professionals can perform simple passive exercises while attending to the patient hygiene. Advice from a physiotherapist may be required.

- Hydration: This also plays an important part (Virchow’s triad) and dehydration should be avoided at all costs. A study by Kelly found that dehydration played an independent role in the incidence of VTE in acute stoke patients (Kelly et al. 2004). Healthcare professionals must ensure that patients have water within reach, and that patients should be reminded to drink.

Interventional thromboprophylaxis is either mechanical or pharmacological. The choice of thromboprophylaxis should be based on local policies, the clinical condition of the patient, the surgical procedure and also patient preference (NICE 2010b).

Mechanical Thromboprophylaxis

Mechanical devices are used to prevent blood pooling in the legs and to encourage venous return. There are three main methods of mechanical thromboprophylaxis: anti-embolism stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression and foot pumps.

Anti-embolism stockings

These stockings provide graduated compression; they have a higher compression at the ankle than the calf, and should comply with the compression of 14–15 mmHg at the calf (NICE 2010b). There has been much discussion regarding the recommended length of stocking as to whether knee or thigh length should be used. NICE guideline CG46 (now obsolete) recommended the use of thigh length but recent NICE guidance (CG92, NICE 2010b) recommends simply thigh or knee length. From the authors’ experience, below knee socks seems most appropriate – patients are more compliant, the stockings do not roll down or cause a tourniquet effect behind the knee when the knee is bent and they are easier to apply for both patient and healthcare professionals and they are more cost-effective.

It may be appropriate at this stage to distinguish between graduated elastic compression socks (GECS) and anti-embolic stockings (AES). The former tend to have a higher compression and usually used to treat patients with poor venous return. These are worn during the day and removed at night. GECS may include lower compression but AES have only lower compression and are worn 24/7 and changed daily. There is often confusion between the two.

Surgical patients who are deemed at risk of VTE should have AES fitted, unless they have contraindications, mainly peripheral vascular disease, excessive oedema of the legs and skin conditions which may be exacerbated by the application of stockings (see NICE guidance C92, for full list of contraindications). Some patients may have a leg deformity that precludes successful fitting. It is important to also use one’s own clinical judgement in deciding whether to fit AES or not, and advice should be sort if in doubt.

Careful measuring and fitting of the AES is important, and all healthcare professionals involved in fitting AES must have appropriate training. Each manufacturer has guidance for measuring and fitting their product and further guidance can be sought from them. Incorrect fitting can cause harm to the patient. A patient with an epidural may not realise that the top of the sock is too tight for example, which can lead to necrosis.

The AES should be changed daily and the foot and ankle observed for signs of pressure sores. In the CLOT study, looking at the effectiveness of AES in preventing VTE in acute stroke patients, it was found that some patients developed pressure sores and from this trial it was recommended that AES are not fitted in medical patients (Dennis et al. 2009). It is important that patients are told about the care and management of wearing AES so that they can ensure that they are removed daily. Patients also need to be informed about how to apply the AES and not to pull them up high and then turn down the top if they are too long as this produces a tourniquet effect and could cause rather than prevent a DVT. Should the calf measurements be different, further advice should be sought as this could indicate the presence of a DVT. Failure to mention this anomaly could endanger the patient’s life as it is dangerous to carry out surgical procedures or fit mechanical devices with an undiagnosed DVT.

Intermittent pneumatic compression

These devices are fitted to the patient’s legs in the form of inflatable leggings or boots and an air pump provides intermittent pulsing pressure to the chambers of the leggings. The exact method of inflation is different for each manufacturer but the principle is the same, encouraging venous return and also stimulating fibrinolysis, the breaking down of clots (Morris and Woodcock 2004).

Foot pumps

Foot pumps are fitted to the patient’s feet and an air pump alternately inflates a cushion in the venous plantar area of the foot and simulates the action of walking, thus increasing venous return.

These devices – intermittent pneumatic compression and foot pumps – are most often used for patients who are deemed at risk of VTE but have a contraindication for pharmacological thromboprophylaxis, for example following neurosurgery and daily evaluation of the requirement for the intermittent pneumatic compression should be documented.

There are two further important points with regard to the use of intermittent pneumatic compression and foot pumps:

- They must not be fitted to patients who have a suspected DVT.

- They should not be placed back on the patient when they have been removed for a number of hours (time determined locally and as per manufacturers advice) as, if the patient has been immobile, there is potential for a DVT to have developed and thus fitting the devices could cause an embolus to move to the lungs.

Pharmacological Thromboprophylaxis

The decision for which drug to be used is based upon local policies and individual patient risk factors, as well as the clinical condition of the patient, for example renal failure and also patient preferences, for example the patient may prefer an oral drug to a daily injection.

Anticoagulants work of different parts of the ‘clotting cascade,’ and in order to understand the action of these drugs it is worth gaining an understanding of this (Bacon 2011). Anticoagulants include:

- low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH, Factor X inhibitor, subcutaneous injection), which is the drug of choice, with enoxaparin, tinzaparin and dalteparin being the most commonly used (Caution needs to be taken in patients with renal failure (defined as eGFR <30 mL/min), depending on the choice of LMWH.)

- fondaparinux (synthetic pentasaccharide Factor Xa inhibitor, subcutaneous injection)

- unfractionated heparin (s/c injection) may be used in patients with renal failure.

New oral agents on the horizon include dabigatran etixalate (Pradaxa), a direct thrombin inhibitor, and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) Factor X inhibitor, currently licensed for prevention of VTE following hip and knee replacements.

Warfarin is NOT recommended for VTE prevention, but patients who are previously anticoagulated with warfarin may be restarted post operatively, using LMWH to ‘bridge’ until the INR is therapeutic.

Aspirin is also NOT recommended for VTE prophylaxis (it is an antiplatelet agent and thus not as effective in preventing venous clots).

Pharmacological prophylaxis should be commenced as soon as haemostasis has been established and the risk of bleeding reduced – hence the requirement for daily assessment of the patient.

Signs and Symptoms of Deep Vein Thrombosis

It is worth having some basic knowledge of signs and symptoms of DVT as it is possible that patients attending the preassessment clinic may have already developed a DVT. Signs/symptoms include:

- pain/aching

- swelling

- oedema

- warmth

- whole leg swelling.

Figure 16.2 Pathway for venous thromboembolism risk assessment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree