Chapter 2

Heart Murmurs

1. What are the auscultatory areas of murmurs?

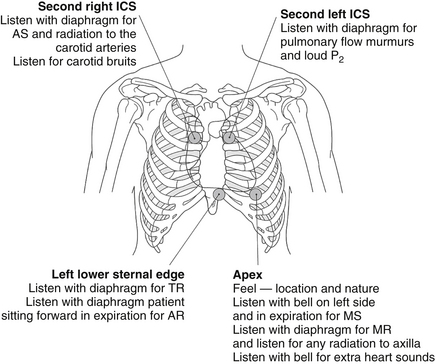

Auscultation typically starts in the aortic area, continuing in clockwise fashion: first over the pulmonic, then the mitral (or apical), and finally the tricuspid areas (Fig. 2-1). Because murmurs may radiate widely, they often become audible in areas outside those historically assigned to them. Hence, “inching” the stethoscope (i.e., slowly dragging it from site to site) can be the best way to avoid missing important findings.

Figure 2-1 Sequence of auscultation of the heart. AR, Aortic regurgitation; AS, aortic stenosis; ICS, intercostal space; MR, mitral regurgitation; MS, mitral stenosis; TR, tricuspid regurgitation. (From Baliga R: Crash course cardiology, St Louis, 2005, Mosby.)

2. What is the Levine system for grading the intensity of murmurs?

1/6: a murmur so soft as to be heard only intermittently, never immediately, and always with concentration and effort

1/6: a murmur so soft as to be heard only intermittently, never immediately, and always with concentration and effort

2/6: a murmur that is soft but nonetheless audible immediately and on every beat

2/6: a murmur that is soft but nonetheless audible immediately and on every beat

3/6: a murmur that is easily audible and relatively loud

3/6: a murmur that is easily audible and relatively loud

4/6: a murmur that is relatively loud and associated with a palpable thrill (always pathologic)

4/6: a murmur that is relatively loud and associated with a palpable thrill (always pathologic)

5/6: a murmur loud enough that it can be heard even by placing the edge of the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the patient’s chest

5/6: a murmur loud enough that it can be heard even by placing the edge of the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the patient’s chest

6/6: a murmur so loud that it can be heard even when the stethoscope is not in contact with the chest, but held slightly above its surface

6/6: a murmur so loud that it can be heard even when the stethoscope is not in contact with the chest, but held slightly above its surface

3. What are the causes of a systolic murmur?

Ejection: increased “forward” flow over the aortic or pulmonic valve. This can be:

Ejection: increased “forward” flow over the aortic or pulmonic valve. This can be:

Physiologic: normal valve, but flow high enough to cause turbulence (anemia, exercise, fever, and other hyperkinetic heart syndromes)

Physiologic: normal valve, but flow high enough to cause turbulence (anemia, exercise, fever, and other hyperkinetic heart syndromes)

Pathologic: abnormal valve, with or without outflow obstruction (i.e., aortic stenosis versus aortic sclerosis)

Pathologic: abnormal valve, with or without outflow obstruction (i.e., aortic stenosis versus aortic sclerosis)

Regurgitation: “backward” flow from a high- into a low-pressure bed. Although this is usually due to incompetent atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral or tricuspid), it also can be due to ventricular septal defect.

Regurgitation: “backward” flow from a high- into a low-pressure bed. Although this is usually due to incompetent atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral or tricuspid), it also can be due to ventricular septal defect.

4. What are functional murmurs?

5. What is the most common systolic ejection murmur of the elderly?

The murmur of aortic sclerosis is common in the elderly. This early peaking systolic murmur is extremely age related, affecting 21% to 26% of persons older than 65, and 55% to 75% of octogenarians. (Conversely, the prevalence of aortic stenosis [AS] in these age groups is 2% and 2.6%, respectively.) The murmur of aortic sclerosis may be due to either a degenerative change of the aortic valve or abnormalities of the aortic root. Senile degeneration of the aortic valve includes thickening, fibrosis, and occasionally calcification. This can stiffen the valve and yet not cause a transvalvular pressure gradient. In fact, commissural fusion is typically absent in aortic sclerosis. Abnormalities of the aortic root may be diffuse (such as a tortuous and dilated aorta) or localized (like a calcific spur or an atherosclerotic plaque that protrudes into the lumen, creating a turbulent bloodstream).

6. How can physical examination help differentiate functional from pathologic murmurs?

There are two golden and three silver rules:

The first golden rule is to always judge (systolic) murmurs like people: by the company they keep. Hence, murmurs that keep bad company (like symptoms; extra sounds; thrill; and abnormal arterial or venous pulse, electrocardiogram, or chest radiograph) should be considered pathologic until proven otherwise. These murmurs should receive extensive evaluation, including technology-based assessment.

The first golden rule is to always judge (systolic) murmurs like people: by the company they keep. Hence, murmurs that keep bad company (like symptoms; extra sounds; thrill; and abnormal arterial or venous pulse, electrocardiogram, or chest radiograph) should be considered pathologic until proven otherwise. These murmurs should receive extensive evaluation, including technology-based assessment.

The second golden rule is that a diminished or absent S2

The second golden rule is that a diminished or absent S2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree